Feeding the Conscience: Philanthropic Food Distribution and Difference in the Popular Press

An illustration by Theodore Davis for the March 7, 1874 issue of Harper’s Weekly (fig. 1) features hungry New Yorkers presenting household vessels to be filled with soup from a steaming vat. Throughout the scene, men, women, and children present lowly and varied containers, their hunger evident in the actions of children who eagerly guzzle soup on the far right and stand on tiptoe, awaiting the attention of the mustachioed chef. In the foreground, a woman with a ragged shawl but erect posture confronts the viewer’s gaze. Nearby, a young boy with a teakettle guides an even younger sibling past a uniformed officer while another recipient of aid looks on, her back slightly hunched over her pitcher of soup. At first glance, Davis’s illustration appears to be a straightforward recording of an urban response to crisis. However, his emphasis on the details of service, charitable aid, and poverty depicts key principles of mid-nineteenth-century charity, including the temporary alleviation of suffering and the division of the worthy from the undeserving.1

Davis’s illustration is part of the substantial press coverage of the opening of soup kitchens in New York City in response to the Panic of 1873. In times of economic and environmental crisis, illustrators for the popular press often produced images of charity that worked alongside text to explain philanthropic processes and to demonstrate the effectiveness of various types of food aid. In addition to this instructional function, depictions of food aid reinforced social boundaries between the recipients of charity, viewers, and those with the ability to offer their time and resources. As a force for difference, these images utilize food and philanthropy as legible and significant markers of class.

Artists’ images of food distribution were particularly important as progressive reforms drove new approaches to philanthropy in the last decades of the nineteenth century. Whereas early American charity sought to provide a temporary respite for those without adequate food, clothing, or shelter, progressive reformers turned to science, data, and instruction in attempts to address the root causes of suffering.2 Artists adopted varied strategies in efforts to depict changing charitable responses. Many illustrators produced detailed drawings that conveyed clear information to viewers, giving visual form to class and social differences suggested by hunger. Others, however, eschewed comforting imagery in favor of more ambiguous scenes that convey the extent of hunger and suffering in the city.

Depictions of charitable food distribution in the popular press utilized hunger as a way to separate viewer and subject. The lack of food provides a platform for the depiction of philanthropic methods, the glorification of donors, and the analysis of recipients of aid by viewers. Notably, in these illustrations from popular periodicals, the aid recipients are overwhelmingly white.3 This is perhaps, in part, a response to waves of (im)migration from the American South, China, and southern Italy, among many other countries, to New York.4 Amid increasing fears about migration and immigration, the focus on the white hungry allowed for images with a clearer meaning. I offer the premise that depictions of seas of hungry white faces was a strategy that allowed artists to focus on economic difference, directing viewers’ attention to their own relative comfort and stability rather than race or (im)migration.

The soup kitchen at 110 Centre Street in Davis’s illustration was one of thirteen soup kitchens under the leadership of the Delmonico family, owners of the posh New York restaurant Delmonico’s.5 These kitchens were also funded by a $30,000 donation from James Gordon Bennett, founder of the New York Herald. The Delmonico name implies that the poorest residents of New York received access to fine French cuisine.6 The text accompanying Davis’s illustration explains, “the soup is prepared under the direct supervision of Mr. Delmonico and his chef de cuisine, Mr. Charles Ranhoffer.”7 Davis’s half-page illustration depicts hungry New Yorkers, many of them children, queuing up for a serving of the “rich hot soup,” made of “materials . . . of the best quality the market affords.”8 This emphasis on quality seems at odds with the image that shows vast quantities of soup in steaming caldrons. Far from the dainty serving vessels in which Ranhoffer’s creations were typically served, the vats reaffirm the poverty of the recipients.

Davis’s illustration is explained as a view of the first day of operations at the 110 Centre Street location. The image carefully depicts key aspects of soup kitchens as explained in the text. For example, his emphasis on children described as both “waifs of misery” and “bright-eyed and smart-looking” allows for a depiction of charity while idealizing the reality of hundreds, even thousands, of New Yorkers unable to feed themselves or their families. Images of hungry children were less likely to draw criticism or to incite fears that may have been provoked by the idea of hoards of unemployed men gathering throughout the city. Davis’s incorporation of a uniformed guard contributes to this sense of security, as do facts presented in the text, assuring readers that soup kitchens are “carefully managed” and housed at police station-houses.9

While the Harper’s Weekly profile focused on providing readers with a framework for understanding the function of soup kitchens, a feature in Bennett’s paper, the New York Herald, dedicates more space to the quality of the food and ingredients. Authors expressed pride in the quality of food at Bennett/Delmonico soup kitchens, consistently referencing their high quality ingredients. The quality of the food distributed is reiterated in the “bill of fare,” which notes that on March 9, those in possession of a meal ticket received “a splendid beef and pea soup . . . half a loaf of bread, made of the whitest flour in the market. The peas, with the large masses of tender beef, made one of the most excellent soups that has yet been offered to the poor.”10 The implication of a bill of fare implies a level of choice not afforded to those who received aid at the kitchens in question. It also skirts the fact that the individuals in Davis’s scene could not pay for a dinner in a restaurant and are not partaking of Ranhoffer’s soup for the pleasure of dining outside the home. The key choice depicted in the image is that of the unseen distributor of meal tickets who decided which individuals were worthy of the fine soups and bread. Readers are assured that “loafers and bummers” would summarily be turned away and that only those “judged favorable [sic] against standards of morality” were permitted to consume the white bread and tender beef donated by the generous business owners of the city.11

The New York Herald feature also applauds donors and organizers of New York soup kitchens. The unidentified reporter notes:

The extent of relief of the outdoor poor existing in this city mainly through the establishment of soup houses is now believed to be amply sufficient, if not indeed more than sufficient to supply the need that is felt by the destitute. Many of the regularly organized charitable institutions have adopted the idea which has been found to work so admirably.12

The novelty of soup kitchens for New Yorkers and their success is reiterated throughout the article.13 Readers are reassured that the facilities are efficient and that soup kitchens were superior to the distribution of alms as a source of aid:

When the first soup house opened many of the men applying were found to be under the influence of liquor . . . Tickets are furnished to residents in the ward who contribute, and these are requested to give no money to beggars but one of these tickets, which entitled the bearer to a meal. This is another means employed to discourage beggars and make them better men.14

The efficient betterment of those deemed deserving of aid was a major priority and foundational principle for New York soup kitchens. Praise for donors and the depiction of surveillance in soup kitchens assured viewers that they would not pose a danger to their neighborhoods. In fact, the kitchens discussed in the March 10, 1874 issue of the New York Herald article titled “Kind Hearts” were housed in police stations and monitored by precinct captains. The presence of a uniformed official, compounded by the service of soup in teakettles from large caldrons, makes the differences between dining at home and waiting in line at a soup kitchen profoundly clear.

The image and text accompanying this article address not only the consumption of soup but also the work of producing large quantities of food and the implied lack of labor of those unable to purchase their own dinner. In the background of Davis’s illustration, three men clad in white uniforms prepare, stir, and distribute soup from enormous vats. At right, a man with a mustache wields a knife as he chops vegetables and meat. On the left, another man exerts a great deal of energy to stir the seaming liquid with a large paddle, while a third distributes soup at the center of the composition. The vigorous and dynamic movements of staff and volunteers highlight the unemployment, stiffness, and even frailty of the unemployed. Although the labor of soup kitchen workers is pushed to the background of the composition, their comparative lightness and dynamic movement draw attention and affirm the virtue of work. The juxtaposition of hunger and labor creates a clear tension between those who participated in the distribution of charity and the beneficiaries; labor vividly contrasting with unemployment.

The distinction between the prosperous and the hungry is made even clearer in the illustration by Charles Broughton of free bread distribution by the baker Louis Fleischman from nearly twenty years later (fig. 2).15 A corpulent, cigarette-smoking figure, perhaps Fleischman himself, looks on as two men distribute large, white loaves of bread to a long line of hungry men. Of course, it is unlikely that the proprietor spent his nights outside distributing bread, but his presence here makes the contrast between the hungry and the wealthy all the more significant. He is depicted in direct contrast with the recipients of his charity; his rotund form is visual evidence of his food security that stands in opposition to their hunger.

In the foreground of Broughton’s illustration, a man with a free loaf of bread tucked under his left arm walks directly toward the viewer. He pulls his collar tight around his neck to combat the cold and stoops forward as if physically crushed by the shame of accepting charity. The second figure approaching the foreground ravenously tears apart his loaf and lifts a large chunk of bread toward his open mouth. His tattered pants and worn shoes depict the sheer urgency of his need. Both Fleischman and the process of bread distribution are detailed and legible, illuminated by a bright streetlight that creates striking contrasts between light and dark. The viewer is invited to evaluate the distribution process and admire Fleischman’s generosity. Viewers, however, would not have felt reassured by the long line of men waiting for bread. The line extends far down the street, blurring into a dark mass. The literal darkness of the line and the darkness of the night, which they were required to confront, reinforce the notion that poverty and charity are dark subjects that must be hidden from the respectable residents of the city. Broughton provided a more sanitized image of breadlines by framing it in the context of Fleischman’s generosity.

The distribution of bread and coffee late at night helped limit access to aid to only the most desperate. As an 1892 article in Harper’s Weekly explained, Louis Fleischman’s Vienna Bakery on Tenth Street and Broadway never denied a man’s request for a free loaf of bread. In order to avoid inconveniencing his customers, he limited the distribution of these free loaves to between 2:00 and 7:00 a.m. “We find them of all sizes and ages, so also we see in the ranks men of all classes and stations in life. They are also of all nationalities. No questions are asked. It is supposed that when a man will come out at two o’clock he is hungry.” The repeated use of “man” is significant here; Fleischman did not distribute bread to women. The text continues, “no women are allowed at night. We will not tolerate them. In the day they come, and we issue tickets that enable them to get bread three times a week. We do not limit them to any amount, but give according to the size of their families.”16 Unlike soup kitchens, Fleischman limited access to charitable food distribution on the basis of gender. While this may have been understood as a way to protect the dignity and reputation of impoverished women, it also made women who worked unable to queue up for free bread. The baker’s adherence to gender norms outweighs his philanthropic impulse. Fleischman’s use of time to deter the undeserving allowed him to exert judgment on working women while limiting which men had access to his bread. By insisting the hungry stand in line at night, Fleischman required them to perform their own poverty.

The issues of unemployment and the indignity of receiving charity were addressed in many images of the period. One full-page illustration published in Harper’s Weekly on January 1, 1894, accompanied by a poem and article, drew attention to the problems of unemployment and poverty. E. V. Nadherny’s illustration Among the New York Poor (fig. 3) is a composite of several scenes, including a free dining room for men; vignettes depicting menial labor of the poor picking coal, kindling, and rags; and a reduced-rate lodging house.17 The accompanying article, written by Junius Henri Browne, “Succor for the Unemployed,” also includes a poem with the straightforward title “Work—Not Alms.”18 On the heels of the Panic of 1893, these three efforts worked together to extol the virtues of labor and the internal struggle of the unemployed as they turn to charity.

The central panel of Nadherny’s illustration notably features the moral struggle associated with the acceptance of charity. In relinquishing the task of providing nourishment when they could not, these men sacrifice dignity and even masculinity to fight off hunger.19 A table full of hungry diners dominates Nadherny’s scene. All of the men are respectably dressed. While some don rumpled suit coats, they all appear reasonably well groomed. Unlike the depictions of soup kitchens, these men are served their dinners while seated and are therefore spared the indignity of waiting, holding bowls, buckets, or bread as in Davis’s or Broughton’s scenes. Each man receives a steaming bowl of soup and a serving of bread, placed directly on the tablecloth. Although this image depicts the distribution of food aid, it also shores up the dignity of the men receiving this aid. This pictorial affirmation of masculinity implies that men were harmed by the inability to secure or maintain employment.20

The author in the accompanying article asserts that the recipients of charity pictured here are not “expectant of alms; nor would they receive assistance from any source if they could earn wages, however small.” A quote from an unemployed man repeats this sentiment more vividly: “The bread of charity almost chokes me.”21 The notion of charity as choking is especially powerful in the context of Nadherny’s illustration, which prominently features a half loaf of bread. Bread, in this instance, stands in as a metaphor for sustenance in general and has historically been a major source of calories, especially for the poor. However, servings of bread on the table raise the specter of whether the pictured loaves have been nourishing or choking. Bread as blockage threatens the life of the eater even more immediately than the chronic lack of food. In this context, charitable intervention could be a threat to the livelihood of the recipient. While bread given by others is a threat, bread that is the fruit of one’s own labor is a wholesome source of sustenance and pride.

Nadherny’s illustration and Browne’s text highlight the indignity of receiving charity as a means of prompting the public to the assistance of those in need during a particularly cold winter. Browne writes:

Nobody need fear their pauperization—a fear that is always sounded. They are not paupers, nor in danger of becoming such, unless assistance be too long withheld . . . Whoever has food, fuel, clothes, should contribute them; whoever has money should contribute that . . . No worthy citizen should rest content without furnishing what he may to the common fund.22

The message here is clear. In explaining the difficulty with which the men pictured accept charity and the seriousness of the need, Nadherny and Browne successfully address fears about misuse of charity and the impoverished to spur action.

Conversely, John Sloan’s 1905 painting The Coffee Line (fig. 4) portrays hunger itself as a threat to the city while critiquing the societal structure that allowed for hunger on such a large scale. The composition features a dark mass of undifferentiated men who brave the snow and cold for a free cup of coffee. While others have noted the orderliness that structures the scene, the dark mass of figures and the blurring of their identity complicate this reading.23 The men create an active disturbance as a dark, ominous mass.24 Sloan’s scene is far removed from Nadherney’s optimistic illustration, which depicts men finding nourishment with some dignity; instead the former depicts a mass of undifferentiated men in a cold and dreary New York night. Streetlights illuminate dirty snow that separates the

line of men from the viewer. The men are depicted as part of the urban landscape, a dark gash between the tree line and street. Sloan described the painting as depicting “winter night, Fifth Avenue at Madison Square, and a long line of cold and hungry men waiting their turn for a cup of coffee. This gratuity was a kindly gesture on the part of one of the newspapers.”25 While Sloan’s statement acknowledges the involvement of the New York City press, it is notable that he has not included the name of the paper on the side of the coffee cart, denying any publicity for charitable deeds and keeping the viewer’s attention on the men.

Sloan’s abstraction contrasts images from the popular press, where detailed scenes allowed viewers to both map their own superior social standing onto images of charity. Clear details that depict the preparation and service of mass quantities of soup and lines of people waiting with buckets for their allotted portion were also instructive for those unfamiliar with urban food aid. In contrast, Sloan’s dark and ambiguous line of men waiting for a comforting cup of coffee has precisely the opposite effect. This image does not attempt to reassure viewers that charitable funds are being well spent, nor does it applaud philanthropic efforts. His stark presentation of poverty and a seemingly inadequate solution to what is clearly a large problem denies comfort for viewers and credit for philanthropists.

While Sloan’s image is a powerful example of his political and social engagement, it depicts what would have been considered by many to be an antiquated, even harmful, form of charity by 1905. While some earlier philanthropists believed that hot soup, bread, and coffee provided economical ways to reduce the suffering of the poor, many Progressive Era reformers favored scientific philanthropy, which aimed to solve the root causes of suffering instead of temporary respite for the poor.26 Scientific philanthropy prioritized education and the use of data to identify and remedy the causes of societal issues. Two particularly compelling manifestations of this were the diet kitchen and instructional courses in food preparation and shopping.27 Diet kitchens distributed food, especially milk, as a medical treatment to the impoverished and ailing. In contrast, home visits and courses on cooking and cleaning promoted assimilation and middle-class housekeeping as ideal.

Carefully constructed depictions of scientific philanthropy in the popular press functioned in varied ways. They assured viewers that the charitable organizations in question were efficient and effective while providing both entertainment and knowledge about charitable practices. More important, these images highlighted differences in the availability of food between economic classes.

One mechanism deployed to depict economic disparities was the glorification of volunteer laborers and instructors at the expense of the needy. One such image, In the Northwestern Kitchen, 1892, (fig. 5), depicts the New York facility at Ninth Avenue and Thirty-Sixth Street.28 As one of six small images included in “The New York Diet Kitchen Association,” by Anna Sterling Hackett, this sketch follows a much larger reproduction of a photograph of A. H. Gibbons, the president of the Diet Kitchen Association. She is depicted as a matronly intellectual, poised with pen to paper and shelves full of books. Her commitment to scholarly pursuits reaffirms the diet kitchen as a scientific approach to philanthropy. Furthermore, the prominence of a reformer as opposed to recipients of charity suggests the importance of process and philanthropic philosophies over the recipients of aid.

The comparatively simple sketch of a matron or volunteer ladling milk into a bucket held by a waiting girl depicts the interaction between provider and charity recipient. In order to get milk from a diet kitchen, one needed a prescription from a doctor for milk to treat illnesses like malnutrition. The image invites the viewer to compare the process of milk distribution with the procedure outlined in the text. Additionally, viewers are given multiple opportunities to assess the effectiveness of the diet kitchen, both in the image and in person; Hackett’s text invited viewers to visit the facility.29 This would have not only been entertaining for a visitor (assuming they were of a higher class), but also useful for establishing their social position and distinguishing their status in contrast to the “sick poor.”30

The New York Diet Kitchen Association was founded in 1873 to work with existing dispensaries to provide food to patients as prescribed by physicians. Based on the principle that “there are bodies to be saved as well as souls,” by 1892, the association ran five diet kitchens.31 The most notable difference between a diet kitchen working with a dispensary and a soup kitchen was the involvement of a physician as a prescriber of food deemed medically necessary. The association kitchens provided beef tea, rice, milk, and eggs in amounts dictated by the dispensary. Patients were issued an order form (fig. 6), which verified their need and conveyed the physician’s instructions to the diet kitchen. These forms both legitimized an individual’s claim to food aid and placed food, especially milk, in the context of medicine and overall health. The growth of diet kitchens was a manifestation of increasing interest in scientific approaches to relief that were taking root in urban centers.

While the five New York Diet Kitchen Association locations worked alongside dispensaries, they were separate institutions. The dispensary itself was not a novel concept. Some of the first dispensaries were founded at the end of the eighteenth century in England as urban alternatives to hospitals for the poor. They generally operated with limited budgets and played an important role in community health, most notably through vaccination programs. While some dispensaries fulfilled a variety of medical functions—even surgery— their most common function was dispensing prescriptions. The notion of prescriptions was, considerably more broad than those filled by a twenty-first century pharmacy. As historian Charles Rosenberg explains in his history of the dispensary, New York dispensary physicians wrote prescriptions for coal to cure “coal fever” in the winter months and for food for those suffering from a variety of ailments.32 Diet kitchens operated under the premise that, “there is no class of persons as wretched as the sick poor. They cannot help themselves and cannot pay to be helped by others.”33 Bolstered by science and bracketed as a medical and societal necessity, diet kitchens were incredibly popular.

In her 1903 discussion of the New York Diet Kitchen Association in the journal Social Service, association president Fanny Garrison Villard explained the history and mission of diet kitchens, emphasizing their distribution of milk. “The Kitchens are not soup kitchens, nor are they cooking schools, but simply the depots from which pure milk, more than anything else, is given free to the sick poor.”34 Much like the illustrations published in Munsey’s Magazine, the quality and purity of the milk is emphasized in photographs of a pasteurizer and the various implements utilized for milk rations included in Villard’s text. The photographs depict milk as both scientific and sterile. In one image, light gleams on the metallic surface of a pasteurizer, a visual reminder of the process to purify milk. Below, rows of glass containers and serving implements recede from the viewer, indicating the importance of precise measurements. The quantity of containers also suggests remarkable productivity. In the context of a journal likely read by industry professionals, these images emphasize milk as a key aspect of scientific giving and eating. The distribution of clean, pure, pasteurized milk was frequently referenced by Villard as the objective of the New York Diet Kitchen Association and was widespread in urban areas.35

Reading depictions of scientific philanthropy in the context of milk and the diet kitchen sheds light on approaches to food aid rooted in science. The emphasis on milk in images is significant in the context of pasteurization and in the prescription of food as part of medical practice. In most images, food and philanthropy are depicted as medically necessary and not just sources of comfort for the hungry poor. As such, these images help to explain scientific philanthropy to the public while positioning viewers in relation to recipients of aid.

In addition to the distribution of milk by the New York Diet Kitchen Association, scientific reformers also emphasized education, specifically, the teaching of skills based on scientific nutritional research that fostered healthful and economic food preparation and consumption. Instruction in cooking and domestic labor was aimed at working-class immigrant families. As other scholars have discussed, Americanization and the eventual elevation of recipients of aid above the need for public assistance were key objectives.36 In New York City, these services were offered through visitors’ programs and settlement houses.37

In a 1909 Harper’s Weekly article, Helen Christine Bennett utilizes both text and image to define organized charity and its emphasis on instruction:

Helping the poor used to be like pouring water into a sieve. You gave to the suffering family in the next block one winter, and the next winter you gave again and again the next, until the family became regular pensioners upon your bounty and you wondered why they never seemed better off . . . But within the last decade charity at large has begun to assume a different form . . . Some ten year ago some of the folk who had literally been pouring water into the sieve got together and determined to plug up the end of the sieve so that the water could not run through.38

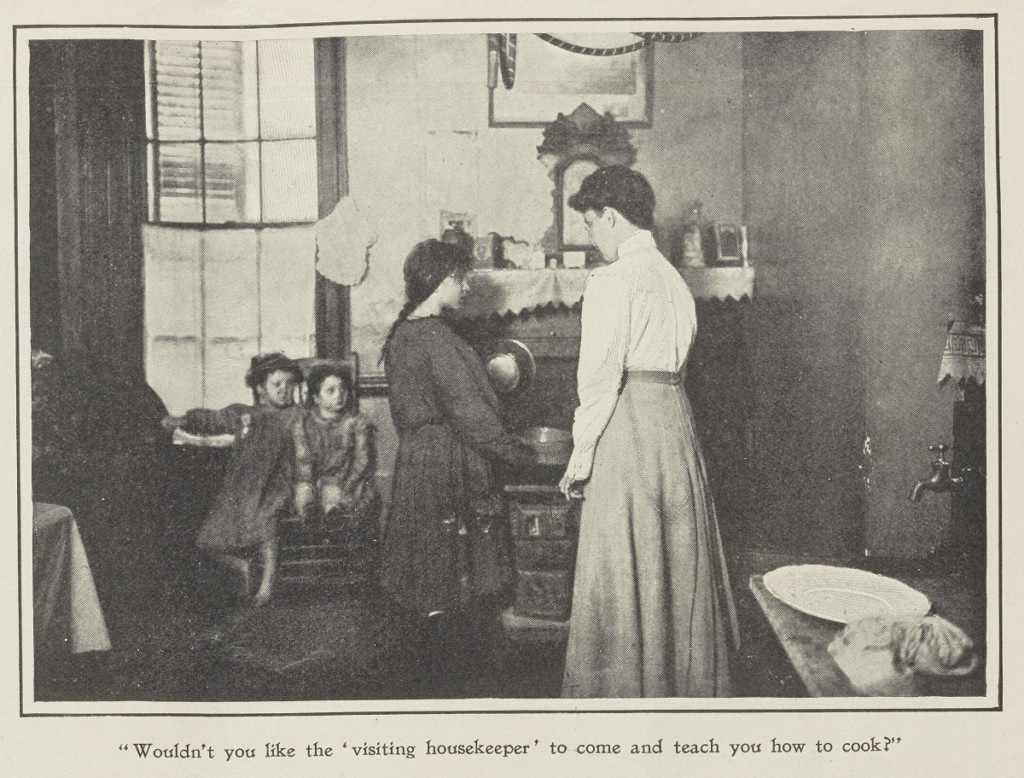

The plug Bennett describes was education. She recounts the employment of visiting housekeepers, cleaners, nurses, and cooks by “organized” charities to instruct the working classes in American housekeeping and food preparation. For the friendly visitors program, run by Josephine Shaw Lowell’s Charity Organization Society (COS), a women served as “advisor-in-chief,” earning the trust of the family, and, eventually, “she enlightens ignorant parents as to the truancy law; she induces the growing children to attend settlement classes; she sees that all have a country vacation; she listens to Willie’s school difficulties and gravely advises the father as to the advisability of giving up the job he is ‘sick of.’”39 The article includes photographs of these varied visitors. In each, a woman clad in white dutifully educates interested women and children in the domestic arts.

Scenes of cooking and housekeeping classes utilized a clear visual hierarchy to differentiate the purveyors of knowledge from those in need of instruction. These illustrations and photographs tend to glorify the work of instructors, benefactors, and distributors of needed foodstuffs, while inviting the viewer to judge those in need of aid. For example, in a photo captioned, “Wouldn’t you like a ‘visiting housekeeper’ to come and teach you how to cook!” (fig. 7) a tall, neatly dressed woman looks on as an adolescent girl inquiringly lifts the lid of a pot. Two small children share a chair in the kitchen, eagerly awaiting the meal to come. The adolescent girl at center expresses an eagerness to learn and deference to the visiting housekeepers. The darkness and dowdy nature of the young woman’s clothing is in contrast to the prim lightness of the visiting housekeeper, creating a clear visual marker of their economic difference. This scene differs substantially from Broughton’s breadline or Nadnerny’s dining room for men in the Bowery were men are depicted as providers and responsible for impoverishment or hunger. Inside the home, the responsibility of preparing food and providing nourishing meals to a family fell to women. Overall, the image makes clear that this is not an equal relationship. The visiting housekeeper is a purveyor of knowledge and health. She possesses status and access to a comfortable life that was designed to inspire her student. The impoverished and immigrant families were expected to defer to the visitor.40

In short, although approaches to the relief of hunger changed in turn-of-the-century New York City, depictions of food aid in the popular press consistently prioritized class distinction. As mechanisms for difference, these images emphasize distinctions between recipients and reformers while assuring viewers of the validity of a given approach to food relief. From the distribution of soup and hot coffee to warm the impoverished on cold New York nights to the regimented fulfillment of prescriptions for milk, depictions of charity reinforced the contrast between hunger and food stability.

Cite this article: Lauren Freese, “Feeding the Conscience,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 3, no. 2 (Fall 2017), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.1608.

PDF: Freese, Feeding the Conscience

- “The Bennett Soup-Houses, Opening of the Sixth Ward Soup-House in Centre Street,” Harper’s Weekly 18, no. 897 (March 7, 1874): 222. ↵

- Early American charity was based on English ideals and prioritized the alleviation of suffering, but within the context of surveillance and the identification of worthy recipients. These charitable practices were rooted in religious mandates of benevolence and self-sacrifice. See Robert A. Gross, “Giving in America: From Charity to Philanthropy,” in Lawrence J. Friedman and Mark D. McGarvie, eds., Charity, Philanthropy, and Civility in American History, (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2003), 33. ↵

- The distributors and recipients of aid in the images that follow are overwhelmingly white. While race is not a focus of this paper, these and other images merit additional study in this context. ↵

- Erika Lee notes that Chinese immigrants were subjected to widespread racism, discrimination, and even violence. This disproportionate prejudice was rooted in Orientalist ideology that homogenized the Eastern Hemisphere and categorized Chinese immigrants as fundamentally different. See Erika Lee, At America’s Gates: The Exclusion Era, 1882–1943 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003), 25. The 1870s was an especially intense period of Italian immigration, in which the more skilled northern immigrants looking to settle permanently in the United States gave way to unskilled laborers from southern Italy seeking short-term financial gain. For more on these subjects, see Erika Lee, “A Nation of Immigrants and a Gatekeeping Nation: American Immigration Law and Policy,” and Guillermina Jasso and Mark R. Rosenzweig, “Characteristics of Immigrants to the United States: 1820–2003,” in Reed Ueda, ed., A Companion to American Immigration, (Malden, Mass.: Blackwell, 2006), 9–14; and 331–33. ↵

- “The Bennett Soup-Houses, Opening of the Sixth Ward Soup-House in Centre Street,” 222. ↵

- Interestingly, the New York Herald also makes a point of calling readers’ attention to the French food available to recipients of charity. The feature specifically mentions a “French cook” employed at the Mercer Street soup kitchen. See “Kind Hearts,” New York Herald, March 10, 1874, 4. ↵

- “The Bennett Soup-Houses, Opening of the Sixth Ward Soup-House in Centre Street,” 222. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- “Kind Hearts,” 4. My use of “bill of fare” as a quotation emphasizes how the text diminishes references to poverty or to the individuals receiving aid by likening the soup kitchen to a restaurant where a patron might have a pick of many dishes, far beyond soup and bread. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- The soup kitchen was not a new type of institution when it was popularized in New York City in the 1870s. The first soup kitchens operated continuously in a set location and are thought to be the innovation of Sir Benjamin Thompson, Count von Rumford, an American working in Bavaria in the 1780s. The discussion of the novelty of soup kitchens in press coverage is likely an assumption that these institutions were unfamiliar to American readers. See Fritz Redlich, “Science and Charity: Count Rumford and His Followers,” International Review of Social History 16, no. 2 (August 1971): 199–207. ↵

- “Kind Hearts,” 4. ↵

- Everett Shinn also depicted Fleischman’s distribution of bread in Fleischman’s Bread Line, dated 1900. The charcoal is located in a private collection. ↵

- “A New York Charity,” Harper’s Weekly 36, no. 1878 (December 17, 1892): 1207. ↵

- While women are depicted performing menial labor in Nadherny’s illustration, the concept of a dining room for the unemployed that was limited to men implies that males were primary victims of unemployment. ↵

- Junius Henri Browne, “Succor for the Unemployed,” Harper’s Weekly 38, no. 1933 (January 6, 1894): 10. ↵

- Ibid. Browne writes, “Nothing can be more afflictive, more crushing, more destructive of manliness, than anxiety for labor and the inability to get it.” ↵

- Notably, women were excluded from the dining room but are pictured performing backbreaking labor around the perimeter of the illustration. While the depictions of food aid in the context of gender is not the central subject of this study, it is possible that the exclusion of women was intended to ease the struggle of the men unable to provide or to encourage women to work in the home. ↵

- Browne, “Succor for the Unemployed,” 10. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Alexis L. Boylan, “Neither Tramp nor Hobo: Images of Unemployment in the Art of the Ashcan School,” Prospects 30 (October 2005): 433–36, 441. Boylan does note the anonymity of the figures but suggests it as a way to prevent viewers from resorting to stereotypes. She briefly mentions the debate over charitable food distribution and the determination of worthiness, but she argues that both Sloan and Shinn reframe this discussion with their paintings. ↵

- Gillian Belnap, “The Coffee Line, 1905,” in Diana Strazdes, ed., American Paintings and Sculpture to 1945 in the Carnegie Museum of Art (New York: Hudson Hills Press, with the Carnegie Museum of Art, 1992), 429–30. Sloan reportedly told art historian Lloyd Goodrich that he removed Hearst’s name from the painting to avoid giving the publishing mogul free publicity; see Don D. Walker, “American Art on the Left, 1911–1950,” Western Humanities Review 8 (January 1954): 330. ↵

- John Sloan, Gist of Art: Principles and Practise Expounded in the Classroom and Studio, Recorded with the Assistance of Helen Farr (New York: American Artists Group, 1939), 205. Also see M. E. Townsend, “Pittsburg’s Annual Art Exhibition,” Brush and Pencil 16, no. 6 (December 1905): 202. ↵

- Judity Sealander, “Curing Evils at Their Source: The Arrival of Scientific Giving,” in Friedman and McGarvie, eds., Charity, Philanthropy, and Civility in American History, 220–23. Sealander explains scientific philanthropy as finding a cure for a disease rather than constructing a hospital. ↵

- Scientific philanthropy took many forms. For an analysis of the scientific giving of America’s wealthiest individuals, see ibid. Beginning in 1898, the New York School of Philanthropy offered courses and lectures on a variety of topics from “The Arrival and Disposition of Immigrants” to “The Financial Management of Charitable Institutions.” See John Louis Recchiuti, Civic Engagement: Social Science and Progressive-Era Reform in New York City (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2007), 58–62. ↵

- The Northwestern Kitchen was located in Hell’s Kitchen, a neighborhood characterized by some of the most notorious tenements, and the target of many Progressive Era reforms. Due to close living quarters and low incomes, Hell’s Kitchen was precisely the type of neighborhood targeted by the New York Diet Kitchen Association. Joseph J. Varga, Hell’s Kitchen and the Battle for Urban Space: Class Struggle and Progressive Reform in New York City, 1894–1914 (New York: Monthly Review Press, 2013), 23–24, 148–49. Food and nutrition reform were important aspects of the programs offered to Hell’s Kitchen residents. ↵

- Depictions of charity in the popular press often featured spectators or invited readers to visit facilities to make their own judgments about the processes and recipients of charity. For example, see David Huyssen, Progressive Inequality: Rich and Poor in New York, 1890–1910 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2014), 89. ↵

- Anna Sterling Hackett, “The New York Diet Kitchen Association,” Munsey’s Magazine 8, no. 3 (December 1892): 279. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Charles E. Rosenberg, “Social Class and Medical Care in Nineteenth-Century America: The Rise and Fall of the Dispensary,” Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences 29, no. 1 (1974): 36. ↵

- “New-York Diet Kitchens: A Charity to Relieve That Helpless Class, the Sick Poor,” New York Times, October 6, 1895, 23. ↵

- Fanny Garrison Villard, “The New York Diet Kitchen Association,” Social Service: A Monthly Review of Social and Industrial Betterment 8, no. 5 (November 1903): 86. ↵

- Ibid. The purity of milk is of historical importance due to a long history of epidemics of streptococcus, typhoid fever, scarlet fever, diphtheria, sore throat, among others, which were linked to milk. Early scholarship linking epidemics to contaminated milk was published in 1881 by Dr. E. Hart in Charles E. North, “Milk and Its Relation to Public Health,” in Mazÿck P. Ravenel, ed., A Half Century of Public Health: Jubilee Historical Volume of the American Public Health Association (New York: American Public Health Association, 1921), 244–50. ↵

- The New England Kitchen was also a force for the Americanization of immigrant cuisine. See Katherine Leonard Turner, “Good Food for Little Money: Food and Cooking Among Urban Working-Class Americans, 1875–1930” (PhD diss., University of Delaware, 2008), 109. Unlike the aforementioned diet kitchen, the New England Kitchens were designed for experimentation and to reform the food habits of the lower class. However, the New England Kitchen as concept was not successful in its efforts, and the flagship Boston location closed in 1907. ↵

- Settlement houses were modeled on a British phenomenon. In the United States, Greenwich Village became a key destination for young, educated men and women looking to transform urban America. See Gerald W. McFarland, Inside Greenwich Village: A New York City Neighborhood, 1898–1918 (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2001), 49; and Daniel E. Bender, “Perils of Degeneration: Reform, the Savage Immigrant, and the Survival of the Unfit,” Journal of Social History 42, no. 1 (Fall 2008): 5–10. ↵

- Helen Christine Bennett, “Helping the Poor to Help Themselves: The Newer Charity Which Searches out and Removes the Cause of Poverty,” Harper’s Weekly (August 28, 1909): 24. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- While this image depicts home visits as helpful and largely unproblematic, profound cultural misunderstandings and insistence on assimilation plagued these programs, as visitors generally lacked understanding of immigrant foodways. ↵

About the Author(s): Lauren Freese is Assistant Professor of Art History at the University of South Dakota.