Enacting Empire: War and the History of American Art

As Maggie Cao observes in the introduction to the Bully Pulpit of which this essay is a part, “accounts of imperialism in American art history have largely been limited to representations of continental territory and Indigenous Americans.”1 Thus a key goal for American art history must be to engage more deeply with US empire, including US empire in places which are beyond the present-day boundaries of the United States, such as the Philippines and Cuba—as several of us do in this issue.

If we shorten Cao’s proposition by a few words, however, we will also find a second, perhaps equally pithy thesis that requires consideration: that “accounts of imperialism in American art history have largely been limited to representation,” full stop. Or, put another way, it may be argued that “accounts of imperialism in American art history” tend to define art primarily or wholly as a set of representational or discursive practices. Thus, while many discussions of the relationships between art and empire offer explanations as to how art legitimized empire or indicated the presence of imperial ways of thinking, few consider more direct connections between the two. Most notably, it is uncommon to find analyses of art that directly address one of the core practices at the heart of empire: the exercise of force in the course of wars of conquest or other military actions.

My own recent research explores the roles played by art within the eighteenth- and nineteenth-century British and US forays into Pacific regions dominated by the Spanish Empire.2 One of my main goals has been to resist a primarily discursive approach. Methodologically, I have employed two primary tools. The first is to engage as fully and intensively with historical processes writ large (which may not, on the face of it, have anything directly to do with art or its practitioners as traditionally defined) as I do with art-historical processes, sources, and methodologies (which, traditionally, have been linked explicitly and often exclusively to makers, collectors, and markets). This means beginning not with known artists, styles, or works of art, but rather with questions about how empire, and processes constituent to it, such as the waging of war, actually proceeded. The second is to embrace an open definition of art that includes not only its creation, exhibition, and market circulation, but also its defacement, theft, and destruction. Although this definition has been used fruitfully by some scholars, it has had only a limited impact in the field of American art (even among scholars who work on empire).3

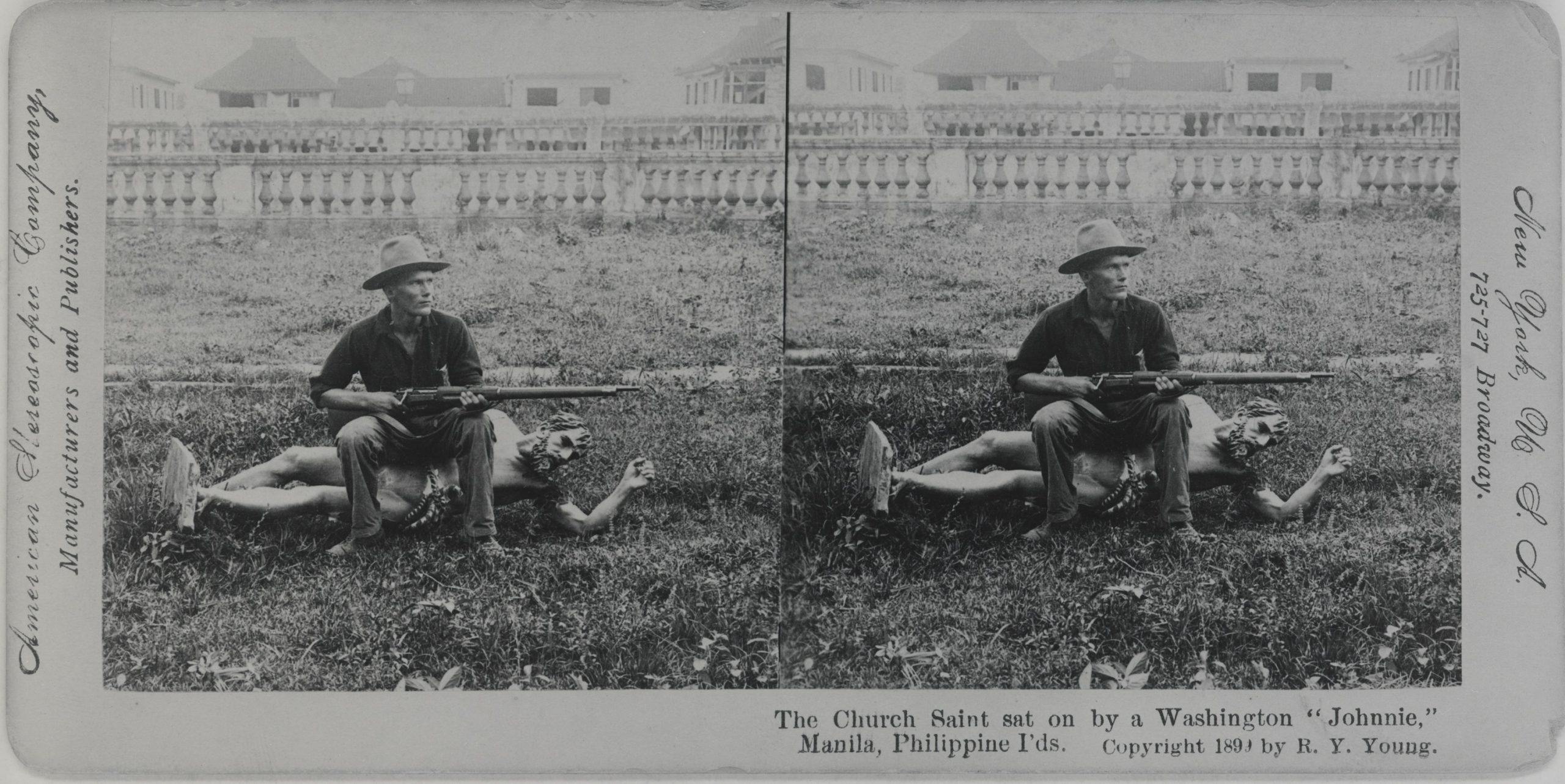

This opening up, I propose, is necessary even in instances where it might be tempting to focus purely or mainly on representation. For example, analyses of photographs produced in the context of US empire in the Philippines have often focused on images made thousands of miles away from the site of conquest, or after the end of the Philippine-American War (fig. 1).4 In contrast, I focus directly on what was taking place in the Philippines during the period of conflict from 1898 to 1902, including a detailed examination of the actions of US military personnel. And in analyzing US images from the very early period of the Philippine-American War depicting the pulling down of statues and the destruction, defacement, and unrecompensed occupation of church buildings and landscapes, I consider it important to analyze not only the images but also those underpinning acts of iconoclastic engagement with the Catholic “political landscape” that they depict.5 From this approach, I came to see both the destruction and the creation of art—the intertwined acts of spoliation conducted by military personnel and their memorialization by photographers, some of whom were soldiers—as not only representations of imperial regime change but also as enactments of the claiming of US sovereignty.6 This interpretation contrasts with much previous scholarship, which has tended to cast art and architecture as a “façade of empire” that was constructed subsequent to the completion of US conquest.7 My approach enables me to demonstrate that art and architecture are not epiphenomenal to conquest but integral to it.

Following this line of thought, I propose that one way art historians can open the field to new subjects is by considering whether traditional definitions of art practice enhance or inhibit the analysis of art in its relationship to empire—and, if it turns out that those definitions limit analysis, by pushing back against the methodological boundaries of the field. At the same time, we need to consider whether the methods we have inherited are built, to a certain extent, upon a disciplinary history of forgetting about empire, and about imperial violence, in particular.

To explore this latter point, consider an example that, on the face of it, is not about empire at all—but that, in obvious ways, is relevant to the history of US art and art institutions: James Johnson Sweeney’s catalogue for the Museum of Modern Art’s 1935 blockbuster exhibition, African Negro Art, which erased the history of colonialism in Africa in order to advance a modernist approach to understanding African art solely in terms of “its plastic qualities.”8

The exhibition was important for various reasons, as Virginia-Lee Webb has argued. It provided a novel opportunity for US museums and philanthropic institutions to engage with elite African Americans. In the context of US exhibitions of African art, it also represented what Webb describes as a departure “from the way African sculpture had previously been treated in a museum context. It was one of the first major museum exhibitions to display these works purely for their formal, artistic qualities, rather than for their attraction as exotic curiosities from ‘savage lands.’”9 In this respect, it also provided the occasion for Walker Evans, in his photographic portfolios of works in the exhibition, to develop his signature style—through, for instance, his use of moving lights to diffuse shadows and the close-cropping of prints.

The exhibition and its catalogue enlisted African art, which Sweeney referred to as “African Negro Art,” in the propagation of a particularly influential way of viewing art and its history that was characteristic of MoMA. In the catalogue, Sweeney insisted that African art ought to be understood solely in terms of “its plastic qualities”—going so far as to assert that “historical and ethnographic considerations have a tendency to blind us to its true worth.” Sweeney did not completely disavow all “historical . . . considerations” as a frame for the works in the exhibition, however; only those he found inconvenient. For, having argued of African art that “historical . . . considerations have a tendency to blind us to its true worth,” he went on in the next sentence to claim, “this was realized at once by its earliest amateurs”—those amateurs being modernist artists in early twentieth-century Paris and Dresden, whom Sweeney credited with discovering “the artistic importance of African Negro art.” Thus, in effect, what Sweeney asked viewers to accept, as the basis for their own validation of African art on purely formal grounds, was historical precedent: precedent in the form of the prior validation of African art by early twentieth-century modernists, and precedent in the form of the prior employment by those modernists, as a means to their own recognition of that art’s worth, of a model of viewing in which they did not know anything about the history of the objects they viewed. As he wrote,

It remains a fact that, about the year 1905, European artists began to realize the quality and distinction of the Negro plastic tradition to which their predecessors had been totally blind. . . . This fact in itself had an appeal for the younger painters of the time, tired of traditions so overlaid with literature that an approach on purely plastic grounds was difficult. Anthropologists and ethnologists in their works had completely overlooked . . . the esthetic qualities in artifacts of primitive peoples. . . . It was not the scholars who discovered Negro art to European taste but the artists. And the artists did so with little more knowledge of the object’s provenance or former history than in what junk shop they had been lucky enough to find it and whether the dealer had a dependable source of supply.10

As this suggests, Sweeney not only made claims about the modernist recognition of African art, but also about the circumstances by which that art had come to be viewed by modernists. According to his model—which might be thought of as the “junk shop” theory of imperial art transfer—African art came to be present in Paris chiefly through the workings of a market centered upon “curiosity” or “junk shops.”

What, then, was at stake in Sweeney’s promotion of this model? Most generally, it asked American viewers to embrace a kind of historical amnesia toward the other key processes by which African art was brought to Paris—notably, the substantial role played by military force—and toward the other significant sites in which the modern European encounter with African art took place, including state institutions such as the Musée d’Ethnographie du Trocadéro. It also asked viewers to accept that modernists knew virtually nothing about their own recent history.11 More specifically, Sweeney’s account also asked viewers to ignore the fact that the MoMA exhibition contained conflict objects that were associated with specific French military campaigns—for example, the “Robe from Béhanzin, Last King of Dahomey” or the “Figure, so-called God of War. Abomey,” which would not have been in New York, let alone France, were it not for the French conquest of the Kingdom of Dahomey (1892–94) and the sacking of Béhanzin’s palace in Abomey. Thus, it prospectively sanctioned future art-historical analyses focusing on Evans’s experiments with representation, or on other topics that situated the analysis of objects within the boundaries of an art world that encompassed the museum but not the battlefield—rather than on efforts to grasp how empire might still be present even in US art and museums.

As this suggests, there are connections between Cao’s observation—that the study of imperialism in American art needs to extend beyond representations of North America—and my own point: that the study of imperialism in American art needs to encompass more than representation. If an imperial war prosecuted by French forces in Africa can be deliberately forgotten by the curators who set the parameters of art history in the US, then surely we can begin to reframe the discipline by learning how to remember that conflict—and the US imperial war in the Philippines that took place in the same period.

Cite this article: J. M. Mancini, “Enacting Empire: War and the History of American Art,” Bully Pulpit, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 6, no. 1 (Spring 2020), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.10086.

Notes

- Maggie M. Cao, “What is the Place of Empire in the History of American Art?,” Bully Pulpit, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 6, no. 1 (Spring 2020), https://journalpanorama.org/article/what-is-the-place-of-empire. ↵

- See J. M. Mancini, Art and War in the Pacific World: Making, Breaking, and Taking from Anson’s Voyage to the Philippine-American War (Oakland: University of California Press, 2018); J. M. Mancini, “The Pacific World and American Art History,” in A Companion to American Art, eds. John Davis, Jennifer A. Greenhill and Jason D. LaFountain (Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, 2015), 228–45; J. M. Mancini, “Disrupting the Transpacific: Objects, Architecture, War, Panic,” Colonial Latin American Review 25, no. 1 (March 2016): 35–55; J. M. Mancini, “Siege Mentalities: Objects in Motion, British Imperial Expansion, and the Pacific Turn,” Winterthur Portfolio 45, nos. 2/3 (Summer–Autumn 2011): 125–40. ↵

- For an excellent exemple of work using this approach, see Andrew Herscher, Violence Taking Place: The Architecture of the Kosovo Conflict (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2010). ↵

- See, for example, Laura Wexler’s influential work, which broke new ground by interpreting Frances Benjamin Johnston’s photographs of the victorious commander of the Asiatic Squadron, George Dewey, and his crew in light of a language of domestic sentimentalism that placed “the imperial house of horrors . . . outside the frame” and made “the visible disappear”—but that focused on images made at a significant geographical and practical remove from the conflict zone by an artist who had no direct experience of either war and never went to the Philippines. Laura Wexler, Tender Violence: Domestic Visions in an Age of US Imperialism (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2000), 35. ↵

- On the concept of “political landscape,” see Adam T. Smith, The Political Landscape: Constellations of Authority in Early Complex Polities (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003). ↵

- See Mancini, Art and War in the Pacific World; Mancini, “The Pacific World and American Art History.” ↵

- Thomas S. Hines, “The Imperial Façade: Daniel H. Burnham and American Architectural Planning in the Philippines,” Pacific Historical Review 41, no. 1 (February 1972): 44. ↵

- James Johnson Sweeney, “The Art of Negro Africa,” in African Negro Art, ed. James Johnson Sweeney (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1935), 12. ↵

- Virginia-Lee Webb, “Art as Information: The African Portfolios of Charles Sheeler and Walker Evans,” African Arts 24, no. 1 (Jan. 1991): 56–63 (quotation on 57), 103–4. ↵

- Sweeney, “The Art of Negro Africa,” 12. ↵

- This is not to say that Sweeney wholly ignored the reality of conquest as a vehicle for the transfer of cultural patrimony from Africa to Europe—he did, exceptionally, recognize the Benin Punitive Expedition (1897), in which Britain’s “African forces had reaped a harvest of Benin bronzes.” However, the selective recognition of this example—which involved troops from Britain, which was not one of his modernist centers—may be read as a deflection away from the French employment of practices similar to Britain’s. Sweeney, “The Art of Negro Africa,” 12–13. ↵

About the Author(s): J. M. Mancini is Associate Professor in the History Department at Maynooth University