Investing in Artists: Ripples of Return

PDF: Cullinan, Investing in Artists

In March 2025 I had the honor of moderating the culminating panel of a three-day exploration of public art and art in public service called “Forgotten Federal Art Legacies: The New Deal to CETA in San Francisco,” organized by Jacqueline Francis, Dean of Humanities and Sciences at California College of the Arts, and Mary Okin, Assistant Director of The Living New Deal Project. The afternoon discussions emphasized themes of memory, momentum, and the interconnected legacies of public art in San Francisco, exploring the labor history and impact of federally funded art from the periods of the Works Progress Administration (WPA) in the 1930s to the Comprehensive Employment and Training Act (CETA) in the 1970s. In the 1970s, thousands of artists across the country were offered jobs through CETA. In San Francisco, everything changed because the city pioneered CETA funding for the arts, investing in artists who then caused a ripple of return that would shift culture and leave a lasting impact.

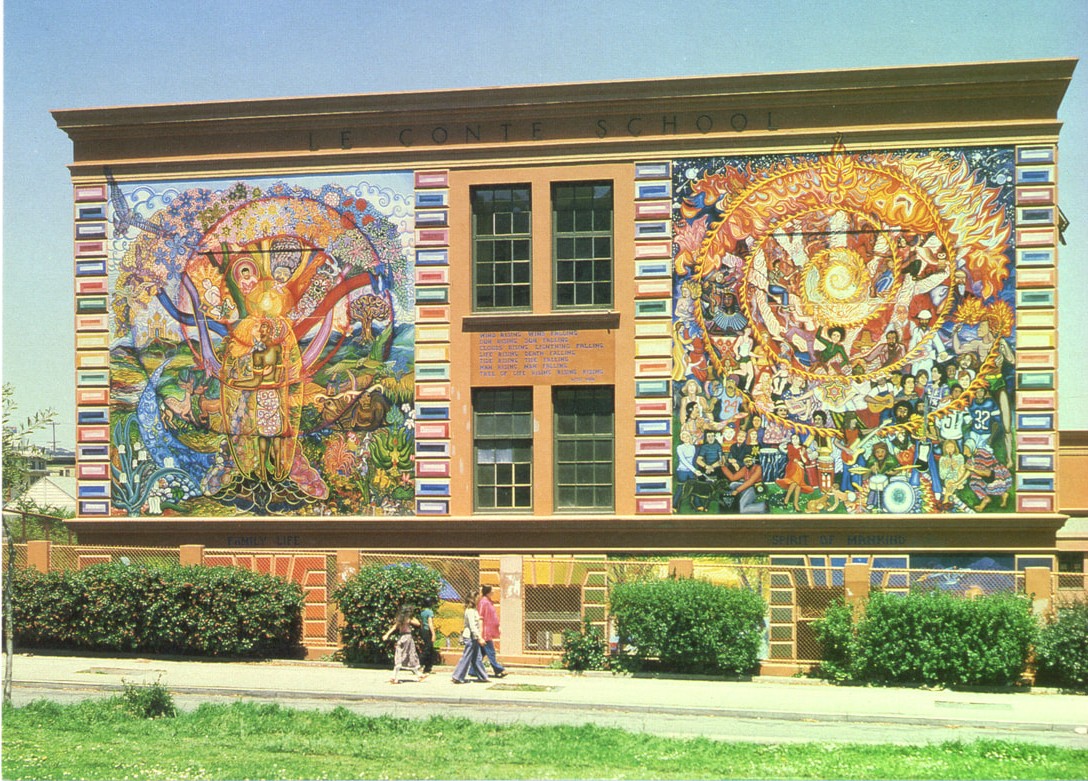

A few examples. Poet and scholar Devorah Major took a CETA job that led to notable residencies at the local, regional, and state levels.1 The legendary Rhodessa Jones (fig. 1) took a CETA job working with children that led to the founding of two iconic performing arts organizations: Cultural Odyssey (with Idris Ackamoor) and the Medea Project: Theater for Incarcerated Women, which touched thousands of women and people living with HIV across the globe.2 Artist Susan Cervantes took a CETA job that led to an expansion of mural painting in the Mission District. She cofounded the world-renowned Precita Eyes Muralists center, which has manifested more than 750 public murals in the city of San Francisco alone, including the CETA-funded and recently restored Family Life and the Spirit of Mankind (fig. 2) at the Leonard R. Flynn Elementary School in the Mission District.3 Artist Nancy Hom and photographer Bob Hsiang took CETA jobs and fueled lasting impact through the Kearny Street Workshop and across the Asian American arts community in the Bay Area.4 Hom was also a curator-at-large for CETA and supported the expanded representation of other communities, their art, and their history, while Hsiang documented both the work of CETA artists and their involvement in local activism. Painter and educator Dewey Crumpler started working for CETA following his completion of the response mural cycle Multi-Ethnic Heritage (1972–74) at George Washington High School in San Francisco, which boldly opened and modeled new understandings of how art can respond to difficult American history and dated American art.5

These are just a few examples of what happens when modest federal investment enables younger artists to be hired to serve local communities. As the stories of CETA alums demonstrate, such formative experiences encouraged artists to invest deeply in community throughout their careers. The impact of CETA, too often forgotten, continued for decades and deserves greater recognition.

These histories, and the artists who took government jobs in order to infuse the city with art and creativity, radically transformed San Francisco’s arts organization ecosystem and have informed just about everything I have done in my career, from serving as the executive director of Intersection for the Arts to leading Yerba Buena Center for the Arts (YBCA) as the chief executive officer.6 At Intersection, I was mentored by John Kreidler, whose influential essay “Leverage Lost” helped catalyze the development of an innovative organizational model that moved away from transacting with artists and audiences and focused on nurturing long-term relationships and creating conditions for artists to realize their full potential and impact in society.7 “Leverage Lost” continues to inform my work today. At YBCA, we piloted one of the first Guaranteed Basic Income programs for artists and, inspired by the CETA Arts Legacy Project, we helped propel the California Creative Corps during the COVID-19 pandemic.8 Today at Stanford Arts, we are piloting a Cultural Policy Fellows program focused on meaningfully integrating arts and cultural practices and ways of thinking into the strategies, policies, programs, and infrastructures of government and policy-focused agencies.9

This work contributes to a national network of artists and arts leaders who have long advocated for integrating the arts into policymaking. Initiatives like Creatives Rebuild New York (CRNY) have effectively stabilized artists’ livelihoods and developed a cultural policy infrastructure for cross-sector engagement.10 Guaranteed Basic Income Pilots, including those by YBCA, CRNY, and Springboard for the Arts, demonstrate that stabilizing artists’ livelihood leads to greater creative output and community investment.11 At the federal level, former National Endowment for the Arts Chair Maria Rosario Jackson advanced a bold policy agenda that linked arts and culture across government agencies, benefiting local communities.12 We now have evidence that artists uniquely engage diverse communities, foster trust and social cohesion, and empower community members to imagine and design their own solutions to the challenges they face.

Today, as we navigate a harsh and complicated world, it feels ever more pressing to lift up and preserve this public work as essential to the landscape of our communities. Federally funded artworks, often cocreated with communities whose stories and traditions have been omitted from dominant narratives, are not discrete to a moment in time. These public projects form a story of people and place connecting us to the past, whether good or bad, while inspiring a sense of what is possible. Perhaps more important in today’s context, they offer an anecdote to historical erasure. Woven into the fabric of our cities, these works and the public policy that funded them remind us of who we are. If we are willing to lose them to time, to overlook or even disremember these histories, we simply will not know who we are, where we have been, and where we are going.

Cite this article: Deborah Cullinan, “Investing in Artists: Ripples of Return,” in “Why Federally Funded Art?” ed. Jacqueline Francis and Mary Okin, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 11, no. 2 (Fall 2025), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.20580.

Notes

- In 2002 Major became San Francisco’s third poet laureate. For more on Major, see https://www.devorahmajor.com. ↵

- For more on Rhodessa Jones and Cultural Odyssey, see https://culturalodyssey.org. For more on the Medea Project, see https://themedeaproject.weebly.com. ↵

- For more on Precita Eyes Muralists, see https://www.precitaeyes.org. ↵

- For more on the Kearny Street Workshop, see https://www.kearnystreet.org. ↵

- Multi-Ethnic Heritage was commissioned by the school following protests over the depiction of Indigenous genocide and enslaved Africans in two panels of Victor Arnautoff’s The Life of George Washington (1936), which was painted on the walls and stairwell of George Washington High School’s main entrance and lobby. ↵

- I served as Intersection’s director from 1996 to 2013. Intersection began in the 1960s as “a merger of several faith-based experiments using art to reach underserved youth” and went on to “convene emerging and established artists, offering them support, space, and opportunities to experiment in poetry, music, theater, comedy, dance, and other artistic disciplines”; it now serves as “a fiscal sponsor for 170+ Bay Area-based members.” “Intersection at 60: A Brief History,” Intersection for the Arts, accessed October 20, 2025, https://theintersection.org/timeline.

I served as YBCA’s executive director from 2013 to 2022. YBCA opened in 1993 and was founded as a “cultural anchor of the Yerba Buena Gardens Neighborhood, and supports contemporary art performance, film, civic engagement and public life . . . centering artists as essential to social and cultural movement.” Homepage, YBCA, accessed October 20, 2025, https://ybca.org. ↵ - John Kreidler, “Leverage Lost: The Nonprofit Arts in the Post-Ford ERA,” Journal of Arts Management, Law, and Society 26, no. 2 (1996): 79–100. ↵

- YBCA’s Guaranteed Basic Income Program provided artists with $1,000 per month for eighteen months. See https://ybca.org/guaranteed-income-for-artists. Preparation to launch California Creative Corps involved interviews with Kreidler as well as Virginia Maksymowicz and Blaise Tobia, the cofounders and cocoordinators of the CETA Arts Legacy Project, https://ceta-arts.com/Legacy.html. California Creative Corps was launched by the state of California in 2021 as a “pilot program, a media, outreach, and engagement campaign designed to increase: (1) public health awareness messages to stop the spread of COVID-19; (2) public awareness related to water and energy conservation, climate mitigation, and emergency preparedness, relief, and recovery; (3) civic engagement, including election participation; and (4) social justice and community engagement,” “California Creative Corps,” California Arts Council, accessed October 20, 2025, https://arts.ca.gov/programs/california-creative-corps. ↵

- For more on Stanford University’s Cultural Policy Fellows program, see https://arts.stanford.edu/office-of-the-vice-president-for-the-arts/cultural-policy-fellows. ↵

- Creatives Rebuild New York was also inspired by CETA. See https://www.creativesrebuildny.org/about/our-story. ↵

- For more information about Springboard for the Arts, see https://springboardforthearts.org. ↵

- For an overview of Jackson’s policies, see “Message from NEA Chair Maria Rosario Jackson,” National Endowment for the Arts, accessed August 14, 2025, https://www.arts.gov/stories/blog/2025/message-nea-chair-maria-rosario-jackson. For specific examples of the work pursued at the NEA in recent years, see the essays assembled in American Artscape: A Magazine of the National Endowment for the Arts, November 1, 2024, https://www.arts.gov/stories/magazine/2024/1/bridges-possibilities-arts-and-built-environment, especially Maria Rosario Jackson’s “Building the Power of Arts and Culture.” ↵

About the Author(s): Deborah Cullinan is the vice president for the arts at Stanford University and coinvestigator of the university’s US Cultural Policy Fellows program.