With Pleasure: Pattern and Decoration in American Art 1972–1985

Edited by Anna Katz

Edited by Anna Katz

Essays by Elissa Auther, Anna Katz, Alex Kitnick, Rebecca Skafsgaard Lowery, Kayleigh Perkov, Sarah-Neel Smith, and Hamza Walker

Los Angeles: The Museum of Contemporary Art; New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2019. 328 pp.; 300 color illus. Hardcover: $65.00 (ISBN: 9780300239942).

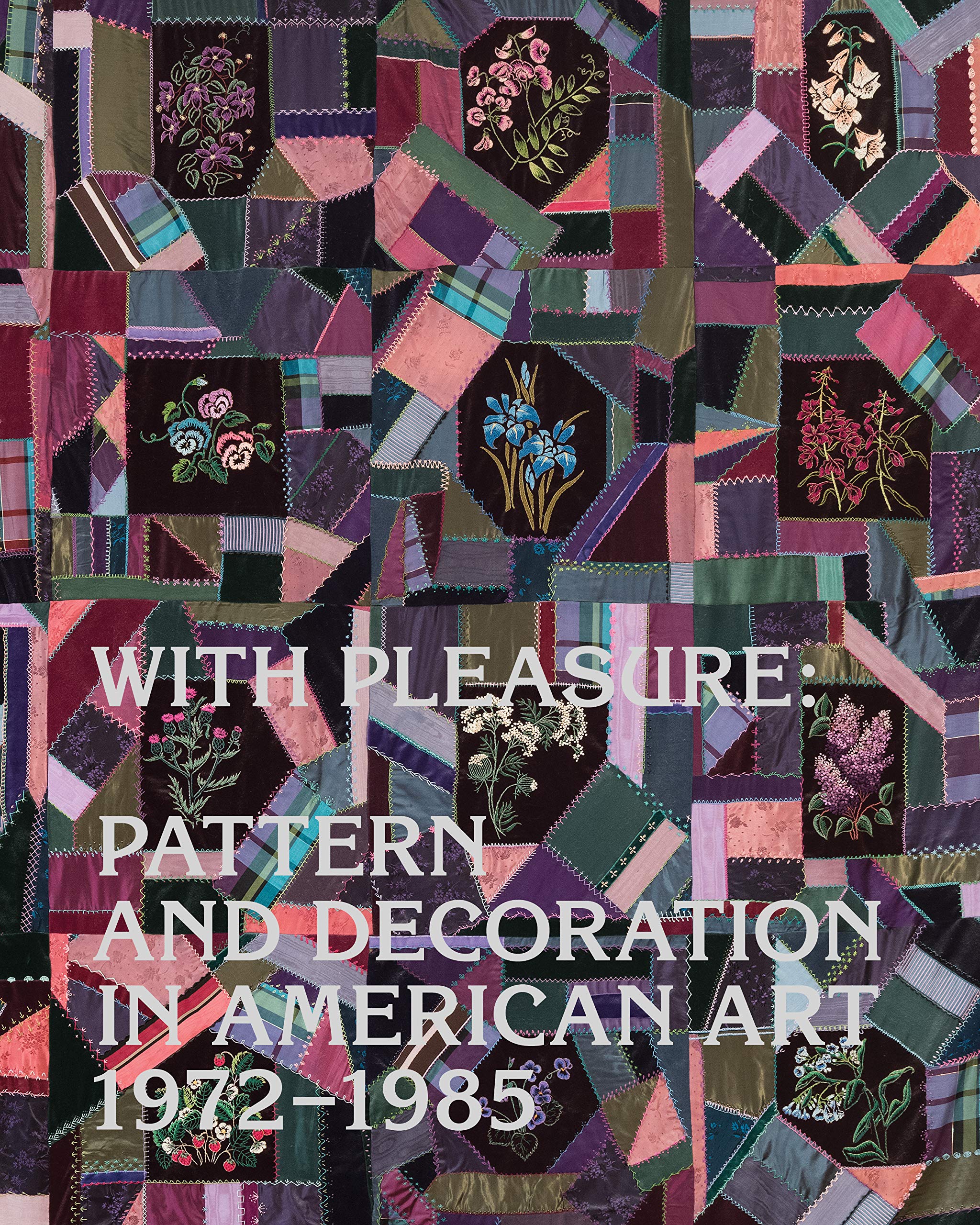

With Pleasure: Pattern and Decoration in American Art 1972–1985 is an ambitious catalogue, wedded to an equally impressive exhibition (fig. 1) held in 2019–20 at the Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art (LA MOCA) and slated for view at the Hessel Museum of Art at Bard College in the summer of 2021. Through the exhibition and catalogue, Anna Katz, LA MOCA Curator, argues for a new, full-body assessment of the status of Pattern and Decoration Art, or P&D. Katz’s inclusion of the word “pleasure” in the title highlights the sensory and visual pleasures offered by work associated with the P&D movement. But of course, joy in art is also controversial. P&D artworks counter modernism’s perceived constraints with their tactility and haptics, which amplify materiality and surface design. Further, the movement is a feminist expansion of abstract practices that rebuffs Modernism’s rules and regulations. These are just some frameworks that Katz and the catalogue’s six essayists explore in this wide-ranging contextualization of the movement. Using what Katz terms an “apparatus of promiscuity,” the authors position P&D artists as creating hybrids drawn from local, US, and global sources (51). Together, the seven essays demonstrate how P&D epitomizes the now-widespread use of diverse and diasporic forms and images.

Pairing eclectic works that use the vocabulary of P&D alongside canonical pieces from the movement, Katz’s volume forms an up-to-date, persuasive, and full-length scholarly study of P&D. The catalogue essays clarify that P&D artists sound a clarion call for visual pleasure and surface abundance. They rely primarily on patterning and decorative components drawn from a seemingly infinite range of sources gleaned from personal content (like the childhood home) and political engagement (such as the embrace of global imagery, patterns, and forms). Working from a Los Angeles-centric perspective, Katz not surprisingly keeps attention on the movement’s California roots, including ceramist Ralph Bacerra (1938–2008) and painter Takako Yamaguchi (b. 1952).

One of the notable aspects here is Katz’s main essay at the start of the catalogue, where she articulates the intricacies and anxieties attending P&D’s relationship with Minimalism, one of its immediate and most important predecessors. Katz outlines the similarities between the two movements, specifically their shared interest in ”architectural scale; emphasis on repetition and nonhierarchical composition through the deployment of the grid; and resistance to the gestural, expressive mark” (20). Significantly, while some of their interests aligned with Minimalism, P&D artists challenged the widespread approach to assessing art in the West, including the promotion of fine arts over decorative arts. This issue is fundamental to their rejection of modernism’s elitist stance and their adoption of what Katz terms “the plentitude of the visual world” (21). This neat distinction crystalizes the determinacy of the P&D movement—it embraced what the art world previously embargoed

Katz amplifies P&D’s parameters, speaking to the current zeitgeist of inclusionary politics by noting significant contributions by artists not typically discussed in the context of P&D, such as African American artists Faith Ringgold (b. 1930), Sam Gilliam (b. 1933), and Al Loving (1935–2005). In connecting such artists with the domesticity of quilts and the political nature of the home, Katz enthusiastically comments: “It is with this in mind that I propose a broader consideration of P&D that accounts for the vitality of quilting as an abstract decorative art form for artists of color in the 1970s and 1980s” (30). By positioning quilting as both abstract patterned decoration and as a consequential expressive format in P&D, Katz generates significant ground for reframing the field. The quilts of Jane Kaufman (b. 1938), in this construct, pivot from the margins to the center of the conversation.

Continuing in this vein, Katz links P&D with the Women’s Liberation movement and second-wave feminism in the 1970s art world (24–25). She focuses particular attention on local California activists, such as Merion Estes (b. 1938) and Constance Mallinson (b. 1948), while also recognizing the role of the Los Angeles-based Women’s Building (1973–91), which Miriam Schapiro (1923–2015) shepherded alongside Judy Chicago (b. 1939). Katz devotes attention to Schapiro’s role as a feminist, positioning the political nature of domesticity and the home as central to P&D. Significantly, underscoring the political involvement these artists had, Schapiro, Joyce Kozloff (b. 1942), and Valerie Jaudon (b. 1945) all participated in the Heresies Collective, a noted feminist artists group in New York City. Another intersection point between P&D and feminist art spaces is Susan Michod, a founder of Artemisia Gallery in Chicago. Katz also quietly pays tribute to the A.I.R. Gallery in New York, considering P&D-related works by artists associated with the gallery, including Mary Grigoriadas (b. 1942), Pat Lasch (b. 1944), Sylvia Sleigh (1916–2010), and Barbara Zucker (b. 1940). One essential scholarly contribution of this essay is how Katz overturns previous anecdotal evidence and draws upon the archive to securely link Zucker, Cynthia Carlson (b. 1942), and Ree Morton (1936–1977) to P&D.

The importance of Miriam Schapiro to P&D is the subject of Elissa Auther’s essay “Miriam Schapiro and the Politics of the Decorative” and is informed by her curation of the 2018 exhibition Surface/Depth: The Decorative After Miriam Schapiro at the Museum of Arts and Design in New York. Auther’s catalogue essay restates her analysis of the interdependencies between high art and craft and expands on the role of the decorative in providing grammar and syntax for feminist expression. She highlights Schapiro’s critical contributions to P&D and feminist art more broadly, as “pioneering a revival of the decorative in visual art in the late twentieth century” that “questions the way we conceive of both high art (painting) and everyday experience (in the form of women’s creative labor in the home)” (80; 81). Auther’s investigation into how Schapiro problematized decoration demonstrates the artist’s importance to P&D, specifically, and to contemporary art more broadly.

Gender remains a topic of interest in Rebecca Skafsgaard Lowery’s essay “Infinite Progress: Criss-Cross and the Gender of Pattern Painting.” Lowery, who is LA MOCA Assistant Curator and worked with Katz on the exhibition, focuses on the utopian artist collaborative community Drop City, started in 1963 near Trinidad, Colorado. Drop City ceased to exist by the mid-1970s and seemed to fade away like many utopian communities. In 1974, it re-emerged with some Drop City members as the Criss-Cross Cooperative in Boulder, Colorado. Pattern painting was one of the main focal points for these artists. The Buckminster Fuller geodesic dome served as a central inspiration for the earlier group, and later artists shared an interest in mathematics as the basis for developing an abstract, geometric, and patterned painting style. Lowery carefully notes the connections and disconnections between Drop City/Criss-Cross and P&D proper and lands on a mutual disinterest in decoration, as well as an absence of gender parity (120–21). Her analysis offers close consideration of the distinctions between the individual artists, including painter George Woodman (1932–2017) and his disdain for decoration, and sculptor Maryanne Unger’s (1945–1998) disinterest in dualism (114–15; 120). While Lowery’s treatment is a much-needed contribution to the literature on Criss-Cross, more attention to the numerous contributors to their journal, Criss-Cross Art Communications, would be beneficial.

The influence of art historian, critic, and artist Amy Goldin (1926–78), her mentor Oleg Grabar (1929–2011), and the much-touted new Islamic art collection galleries of the Metropolitan Museum of Art form the subject of Sarah-Neel Smith’s essay, “A Meeting of Two Minds: Oleg Grabar and Amy Goldin on the Met’s Islamic Art Galleries, 1975.” An art historian specializing in late Ottoman and early Turkish art, Neel has an interest in cultural interactions between the Islamic world, Europe, and the United States. Her essay is vital for its estimation of how Islamic art was framed for artists of the era through contemporaneous geopolitics and the intellectual efforts of Goldin and Grabar. Unfortunately, with the exception of one passage in Katz’s introductory essay and the inclusion of a critical text by Goldin in the historical reprints, the significant critical projects of Goldin get short shrift within the catalogue at large.

Hamza Walker, executive director of the Los Angeles nonprofit art space LAXART and an adjunct professor at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, contributes “Rebecca Morris and the Revenge of P&D.” In this essay, Walker offers a thought-provoking analysis of feminism and P&D, perceptively illuminating a compelling reason for P&D’s complicated reception: “It is easy to be ironic about P&D. It can be hard to look it in the eye and even harder to avail oneself to a course of painterly exploration in which you don’t choose your bedfellows” (182). Here, Walker successfully grapples with and conveys the overlapping concerns of Rebecca Morris (b. 1969), a thoroughly postmodern artist for whom the painting is always a palimpsest, with conceptual artist Daniel Buren (b. 1938), and P&D artists Valerie Jaudon (b. 1945), Robert Kushner (b. 1949), and Robert Zakanitch (b. 1935).

Kayleigh Perkov’s contribution, “Pattern Consciousness: Counterculture-Influenced Interior Design,” centers on the explosion of surface patterns and colors throughout US interiors in the 1960s and 1970s. A curatorial fellow at the Center for Craft in Asheville, North Carolina, Perkov explores the enthusiasm for patterning and decorative motifs at midcentury that “owes intellectual debts to a pop cultural notion of expanded consciousness, urging sensual experience and individuality” (218; 216). She historicizes “pattern-on-pattern,” arguing that it resulted from a short-lived embrace of the counterculture and that “it is this removal of hierarchies and the mixing of tropes in service of rebellion that produces the pattern-consciousness found in both trends” (223). In this way, Perkov continues a theme of the P&D movement (and catalogue) when she describes how robust visual patterning flipped traditional hierarchies by giving the decorator status usually reserved for the designer.

With Pleasure is beautifully illustrated with color images and also contains historical reprints, artist biographies, exhibition histories, an exhibition checklist, and a bibliography. Because it takes such an expansive approach to P&D, it collects previously dispersed materials into one much-needed volume. Ultimately, the P&D movement, which ran counter to modernism’s stern austerity, gets its due. The uninitiated will be introduced to the movement and its concerns, and curatorial attention will translate into museum acquisitions. All told, the catalogue allows these artworks to delight audiences once more, showcasing the issues the artists tackled.

Cite this article: Anne Swartz, review of With Pleasure: Pattern and Decoration in American Art 1972-1985, ed. Anna Katz, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 7, no. 1 (Spring 2021), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.11850.

PDF: Swartz, review of With Pleasure

About the Author(s): Anne Swartz is Professor of Art History, Savannah College of Art and Design