Indigenous Temporal Enmeshment in Akwesasne Notes

PDF: Schmitz, Indigenous Temporal Enmeshment

Author’s note: I would like to begin by stating that, as a non-native settler living in what is presently known as the United States, I do not speak for any Native person or nation(s). I offer my profound respect for all Indigenous creators mentioned in this article, which has been significantly informed by the work of Native scholars, artists, and cultural knowledge keepers. However, I am responsible for any gaps in my understanding or interpretation of this material, and I offer my observations humbly. While it should not be seen as a move to innocence, what I have attempted to do with this article is to make the art and design community more aware of Akwesasne Notes as an under-researched subject that deserves recognition and inclusion in our discussions surrounding twentieth-century decolonial media and counterculture graphic design history. The American Indian Digital History Project was instrumental in my introduction to the broad scope of Akwesasne Notes’ graphic and illustrative contributions. I thank the researchers and educators at the University of Kansas and the University of Nebraska at Omaha for creating this open-access resource, which I encourage everyone to visit. I also thank former Notes editor Doug George-Kanentiio, whose published work on Akwesasne Notes fleshed out my understanding of the Mohawk community and their histories. Finally, I would like to heartily thank former Notes layout artists and editors Clayton Brascoupe and Alex Jacobs/Karoniaktahke for providing me with important personal accounts of their time at Notes.1 I send gratitude to The Mohawk Nation Council of Chiefs, Indian Time, and the Panorama editorial team for their help and guidance as well. This article is dedicated to all past, present, and future Indigenous creators.

Introduction

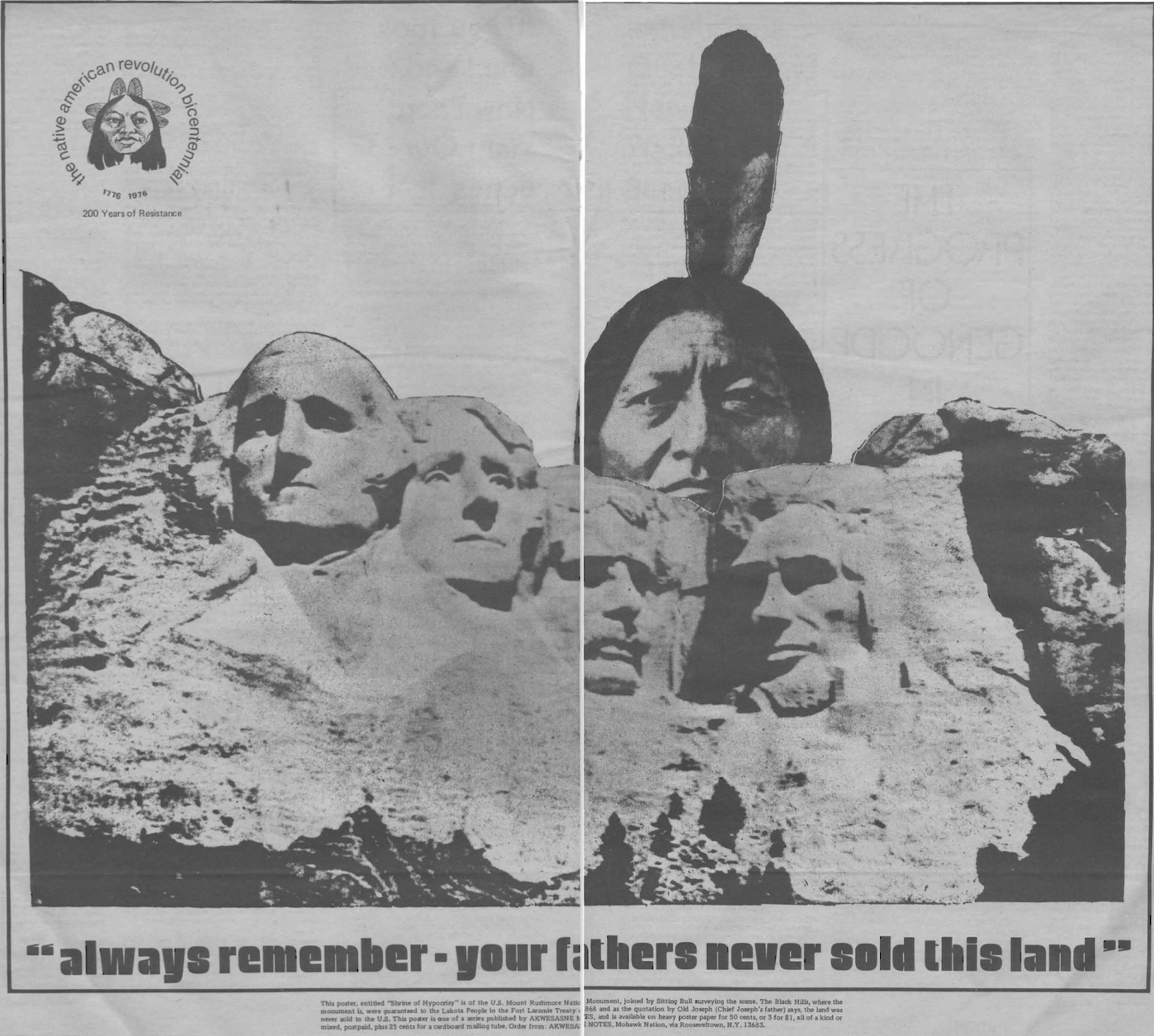

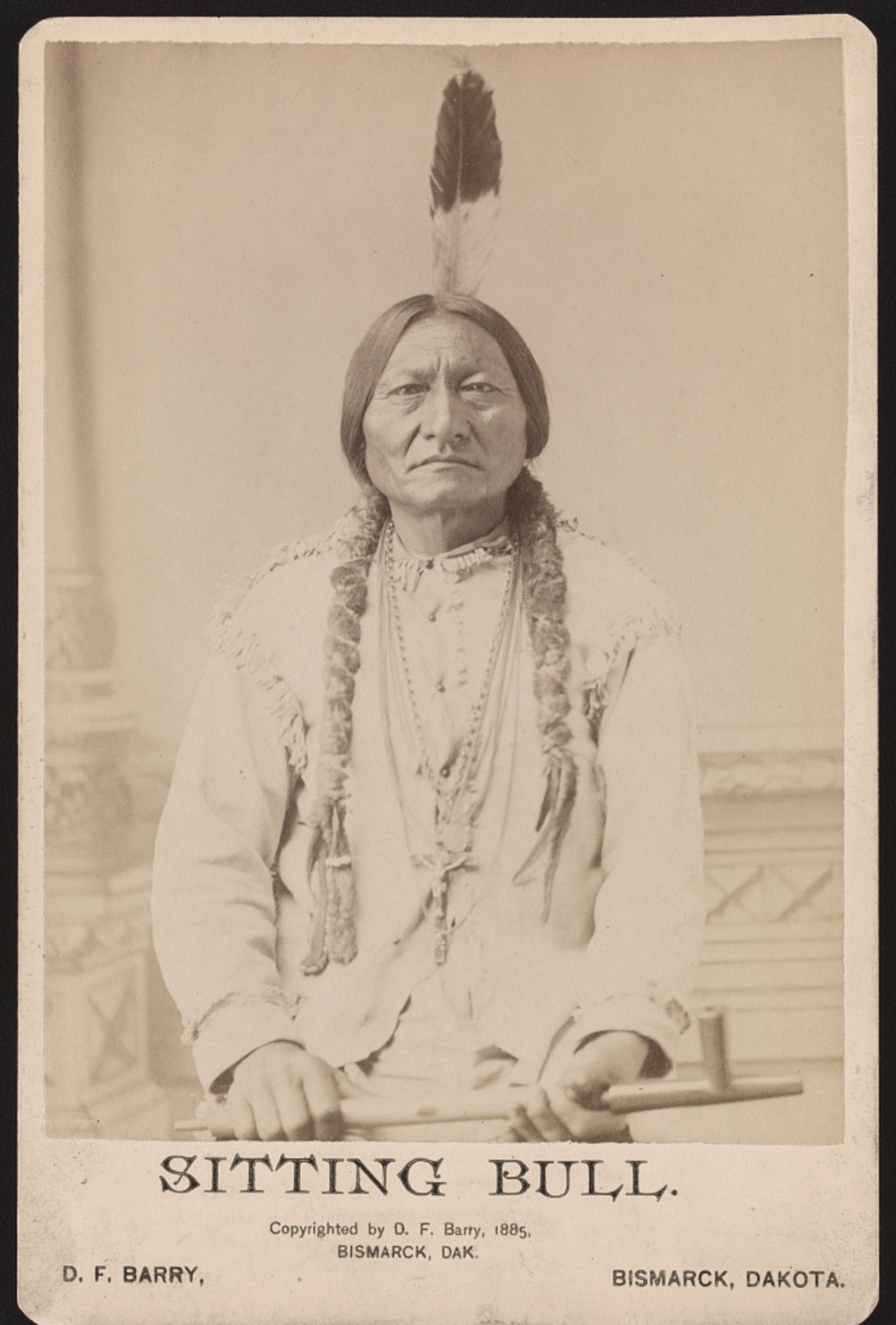

In 1975, the Mohawk-run newspaper Akwesasne Notes published a poster titled The Shrine of Hypocrisy (fig. 1). The poster contains a picture of Mount Rushmore National Monument together with a cropped image of Sitting Bull’s head taken from David F. Barry’s 1885 portrait of the Hunkpapa Lakota holy man and warrior (fig. 2). Called Thunkášila Šákpe (Six Grandfathers) by the Sioux, the mountain popularly known as Mount Rushmore was given its colonial name after a wealthy New York lawyer the same year Sitting Bull’s portrait was made. Plucked from his original portrait, which was a commodity in Barry’s photography studio, Sitting Bull looms over the carved faces of the imperialist project, scrutinizing what has become of the sacred Black Hills and its Six Grandfathers. The wrinkled granite grandfathers were chiseled solely by the elements until the year 1927, when the white artist Gutzon Borglum began his sculptural project, which was conceived as a symbol of freedom and patriotism, a shrine to democracy. Each president featured, however, had implemented their own genocidal strategies on Indigenous people. Thomas Jefferson was a passionate assimilationist and is recognized as the initial architect of Indian removal policies, most famously exemplified in his orchestration of the Louisiana Purchase. Abraham Lincoln ordered the largest mass execution in history following the Dakota uprising: thirty-eight Indigenous men were hanged the year he signed the 1862 Homestead Act into law, which further incentivized violent Western expansion. During his presidency, Theodore Roosevelt transferred millions of acres of tribal land to the US federal government. His infamous 1886 quote—“I don’t go so far as to think that the only good Indians are the dead Indians, but I believe nine out of every ten are”—perhaps best summarizes his feeling about Native peoples. In Sitting Bull’s day, the site, which is located in the Lakota’s sacred Paha Sapa (Black Hills), was a major point of contention between the Sioux and the US government, who wished to open the area to white settlers after gold was found there in 1876. Bogus treaties were signed by unauthorized individuals, and the land was soon overrun.

Sitting Bull is best known for his leadership alongside Crazy Horse at the 1876 Battle of Greasy Grass, which saw the destruction of Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer’s Seventh Cavalry and marked a major victory for the Sioux as they attempted to retain the Black Hills. In December of 1890, fearing he would join the Ghost Dance resistance movement, the US government facilitated Sitting Bull’s arrest and assassination at the Standing Rock Indian Reservation in the Dakota Territories. Just a few days after Sitting Bull’s death, the Wounded Knee Massacre saw three hundred Lakota men, women, and children murdered by Custer’s former regiment. The Ghost Dance movement that helped support and inspire Indigenous resistance in the West was started by a Paiute holy man, Wovoka, who, after receiving a series of visions, prophesized that if the Native people lived peacefully, danced this new dance, and sang the Ghost Dance songs, their world would revert back to the old one, ancestors and the buffalo would rise from the dead, and the white settlers would disappear. Mark Rifkin has shown that “prophecy emerges [in late twentieth-century Indigenous texts] as a catalyzing force that punctuates and animates Native frames of reference,” so that, consequently, “modes of prophetic duration . . . exceed the parameters of settler historicity.”2 In a similar manner, The Shrine of Hypocrisy refuses the idea that the Ghost Dance prophecy was debunked at the so-called closing of the frontier in 1890. Instead, it visualizes the prophecy: Sitting Bull has risen in 1975 to help in the contemporary defense of Indigenous futurity. A quote in bold letters below the collage, reportedly among the last words of Nez Perce Chief Old Joseph as he lay on his deathbed in 1871, reads, “Always remember—your fathers never sold this land.” The image disrupts the colonial temporal narrative and its prognostications about the land and its people by enmeshing moments in time that prioritize Native narratives, historical perspectives, and land stewardship in the present.

In 2009, curator Henrietta Lidchi and Seminole-Muscogee-Navajo artist and scholar Hulleah J. Tsinhnahjinnie stated, “For Native communities, archives formerly identified as a place of subjugation are now more frequently the sites of reclamation and retrieval.”3 Of particular interest to Indigenous artists, scholars, and educators are archival photographs and portraits of nineteenth-century Indigenous leaders previously used as commodities by white photographers or studied and categorized as ethnographic specimens. Since their earliest contact with Indigenous peoples, non-native people have attempted to control, or obliterate, Indigenous stories, worldviews, sovereignty, conceptions of self, and histories. In addition to the acts of genocide and epistemicide that supported Manifest Destiny, various legislative measures were passed to diminish Indigenous claims to land and lifeways over time. In short, the future of Indigeneity, according to settler doctrine, was and is subtractive. These beliefs were supported by several tropes present in historical portraits of Indigenous people by non-native people. Ariella Aïsha Azoulay has helpfully applied the term “imperial shutter” to photography’s ability to deny historical alterity and prioritize colonial interpretations of space, bodies, and time.4 Through the imperial shutter, Native Americans were constructed in the settler racial imaginary as a monolithic people, destined to vanish. By appropriating and recontextualizing images like Sitting Bull’s 1885 portrait, Native artists and designers can disrupt colonial linear time and its narrative about inevitable white progress and Native erasure, as well as the imperialist project’s grip on identity and possibility. This article attempts to analyze one of the first instances in which Indigenous artists reoriented historical portraits with text for these purposes.

During the 1970s, at the height of the American Indian Movement (AIM), a handful of Native-published newspapers offered a mix of editorials and news on Native issues. Akwesasne Notes, published by the St. Regis Mohawk Reservation between 1969 and 1997, was the widest circulated and most abundantly illustrated newspaper of its kind.5 The paper, known colloquially as Notes, was published around six times a year, with extra issues some years due to AIM’s activism throughout the 1970s. Notes was distributed to subscribing individuals, libraries, and schools, as well as directly to Native and non-native people through the Haudenosaunee traveling educational group, White Roots of Peace. Like other radical newspapers at the time, including the Black Panther, Notes was the press arm for a large anticolonial movement and was full of illustrations, tailpieces, and posters created by the Mohawk Nation at Akwesasne or by sympathetic outside artists. Because the colonial narrative of time assumes the eventual absence of all Indigeneity, the Notes staff often went back to the imperial photographic record and manipulated it with text to provide an alternative view of history while asserting Native contemporaneity. Consequently, Notes seized temporality from the arsenal of colonial weaponry to affirm Indigenous presence and futurity.

Using historical portraits of Indigenous people, the artists and designers involved with Notes originated a method of temporal enmeshment as a rhetorical strategy of decoloniality. This technique is found today in the work of several contemporary Native artists, such as Wendy Red Star, Marcus Amerman, Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, Larry McNeil, and Shan Goshorn, among others. Despite the newspaper’s dynamic graphical layouts, its contributions to the visual cultures of decolonization and social justice during the political and social upheavals of the 1970s, and its impact on contemporary artistic critiques of imperialism, Notes has never been deeply explored by art and design historians.6 The present article begins the investigation. The study uses information gathered from former Notes volunteers and staff members as well as historical and visual analysis of the periodical’s imagery and layout as evidence.

Temporal Enmeshment as Indigenous Survivance

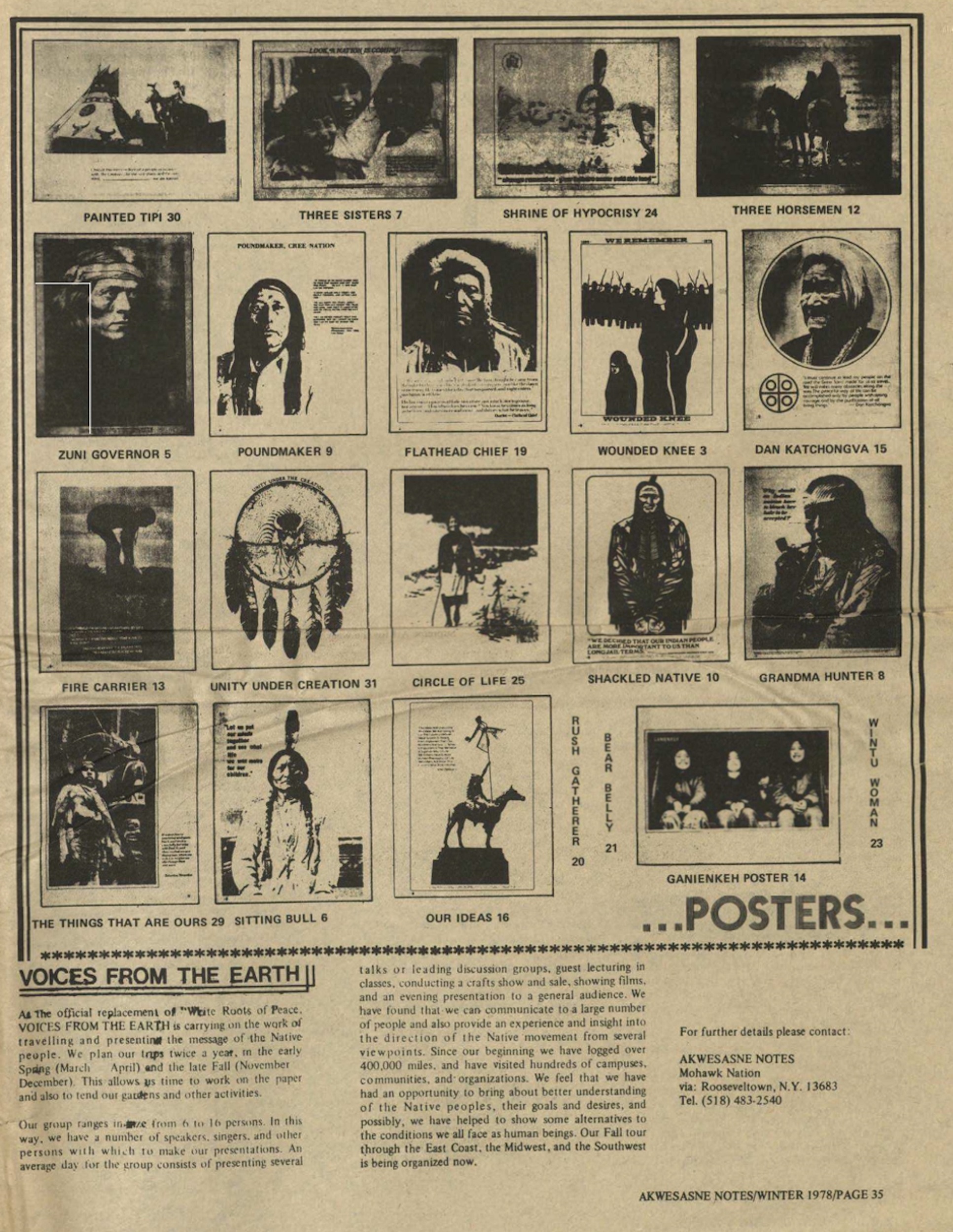

This article’s specific concentration is a series of poster centerfolds and poster advertisements dispersed throughout the newspaper and sold for one dollar by mail order between 1971 and 1978 (fig. 3). Many of the images appropriated, cropped, and manipulated in the posters were portraits of Native leaders taken and commodified at the turn of the twentieth century by white photographers. Notes editors and designers strategically chose to feature these turn-of-the-century Indigenous portraits because they carried powerful weight in American mass consciousness, and they knew this power could be harnessed. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, photography blurred the lines between scientific, social, and artistic designations. Its problematic association with “truth” gradually contributed—aided by Wild West shows and eventually Hollywood Westerns—to the wide reception of a contrived Native identity that perpetuated essentialized stereotypes developed by colonizers. The Native people in the portraits of Charles Milton Bell, Frank A. Rinehart, David F. Barry, and Edward Curtis, for instance, are often removed from their historical context and are usually shown wearing customary clothing that conveyed the sitter, and Native identity more broadly, as somehow stuck in a historicized past. Gerald Visenor defines such images as “poselocked fugitives of ethnocentric discoveries.”7 While the sitters undoubtedly understood the power of self-presentation, curator Jill Sweet suggests that the subtext behind the portraits’ frank gaze for white audiences was not cool defiance but “the idea that Native Americans are victims who see their own futures coming to a tragic end.”8 Consequently, these photographs perpetuated the well-worn stereotypes of the “noble savage” and “vanishing Indian.” These myths, having been visualized and solidified by the imperial shutter, served to encourage Western expansion and the theft of Native land.

As Tuscarora scholar and historian Jolene Rickard points out: “Photography became prominent at precisely the same moment that the American government was staging the take-over of the great Plains. The combination of these layered events created a powerful imaginary image in the mind of most Americans about the Indian.”9 The late nineteenth century was also an important moment for Indigenous resistance, as the US government ramped up its efforts to relocate the remaining Native people who refused to reside on reservations. Notes staff recognized that they were still facing battles regarding sovereignty over the land and lifeways their ancestors had fought for in previous generations. Former layout artist and editor at Notes Clayton Brascoupe (Mohawk/Anishnabeg) remembers looking over the photographs fondly, “whoever the photographer was,” and recognizing that the sitters outwardly communicated a power that could resonate in the present: “Looking back on the strength of our parents, grandparents, and ancestors inspired present-day activists who were also facing difficult circumstances.”10 Brascoupe’s reflection connects with Apsáalooke artist Wendy Red Star and curator Shannon Vittoria’s argument that to interpret all such photographs exclusively as symbols of settler domination would “deny the ambitions and intentions of the sitters, who . . . actively fashioned themselves as independent leaders of a sovereign nation.”11 By collaging the portraits with quotes from celebrated holy people, warrior ancestors, and contemporary activists, Notes galvanized and united Indigenous peoples in the present fight for Native sovereignty, many years after the photographs were taken and most of the quotes were recorded. In the process, Notes reincarnated these ancestral leaders, renewed their power and agency, and, in a way, gave the photographed, commodified, and romanticized figures their voices back.

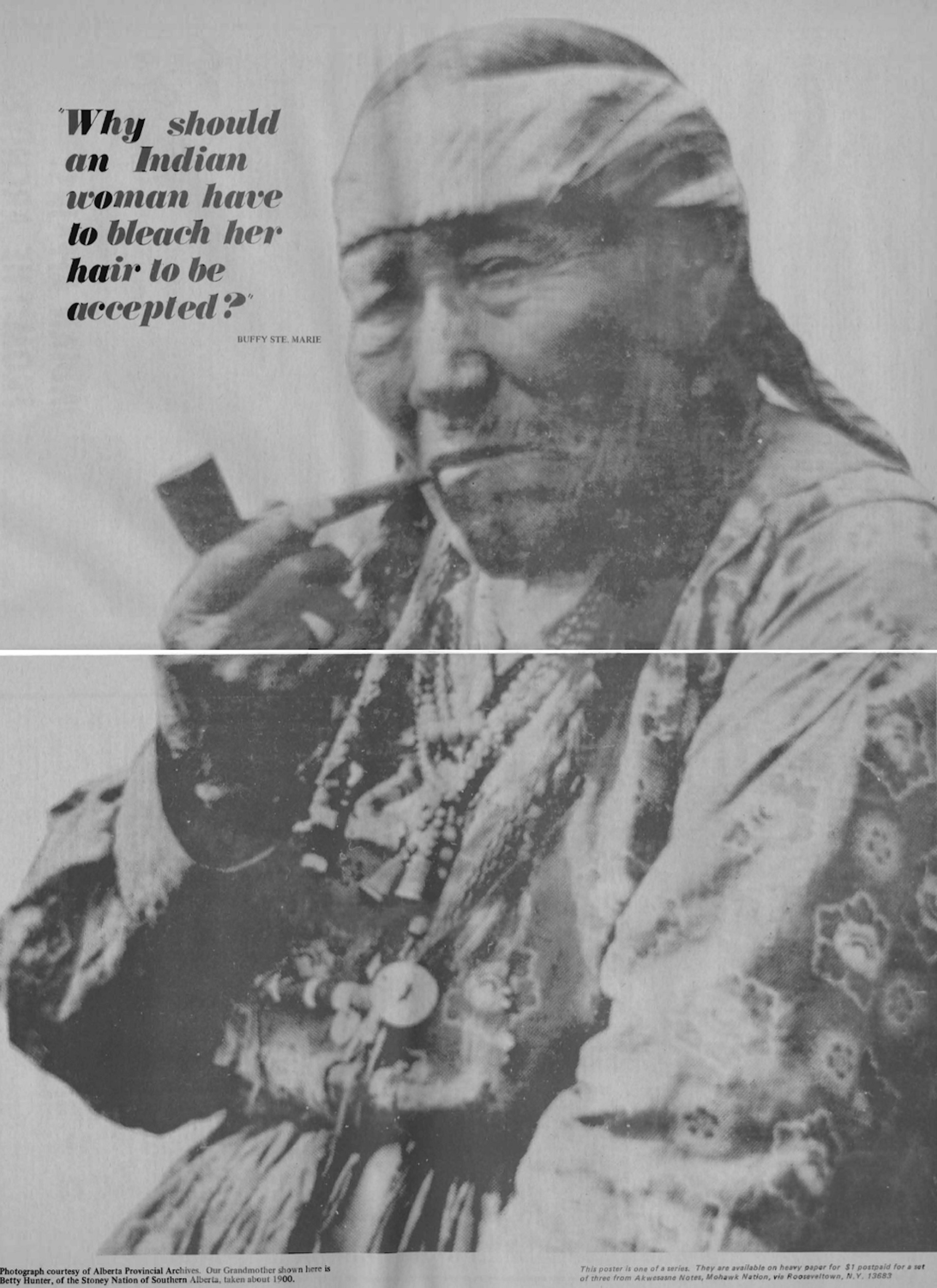

Temporal enmeshment is a key tactic in Notes posters, since the method helps visualize Indigenous survivance. In one sense, I use the phrase to describe the way Notes editors and designers constructed their posters: each is a literal enmeshment of photomontage and text, which are, respectively, appropriated from different times, places, and circumstances. Consequently, the posters offer an outlet for ancestral guidance that is unbound by space and time. One poster, for example, contains a found photograph sourced from the Alberta Provincial Archives of an elder named Betty Hunter, who gazes wryly at the viewer while smoking her pipe (fig. 4). The text on the left, a quote from contemporary Native singer-songwriter and activist Buffy Sainte-Marie, reads, “Why should an Indian woman have to bleach her hair to be accepted?” The resulting didactic prevents the formidable Hunter from remaining an anthropological document, filed away and abandoned in the past. She is instead able to advocate for an Indigenous future absent of prejudice as she speaks through Sainte-Marie in the present. The spectral nature of temporal enmeshment is integral to the poster’s function.

Temporal enmeshment reveals that prognosticating the future of Indigeneity involves following ghosts and being followed by them. C. Ree and Eve Tuck’s work on the threat of haunting to settler colonialism is relevant: “Settler colonialism is the management of those who have been made killable, once and future ghosts. . . . Haunting, by contrast, is the relentless remembering and reminding that will not be appeased by settler society’s assurances of innocence and reconciliation.”12 The revived ancestors in the Notes posters pose a real threat to colonial linear time and false assumptions about a future devoid of Indigenous people because these individuals are now capable of residing in any temporal location: past, present, or future. Ultimately, Notes designers created temporal enmeshments in their posters to critique colonial understandings of history and linear time by articulating an ancestrally informed, future-making agenda in single images.

Given Akwesasne’s geographic position and the Mohawk’s political agility, it makes sense that such a periodical would develop there. The Mohawk territory of Akwesasne uniquely covers two countries: the United States (New York State) and Canada (Québec and Ontario). The presence of the community emphatically demonstrates the arbitrariness of colonizer borders set up after the War of 1812.13 The newspaper’s founding coincided with the 1969 blockade of the Seaway International Bridges between Cornwall Island and Akwesasne, which had been instigated by young Mohawks protesting customs taxes imposed on reservation residents crossing the US-Canada border. With the release of a documentary film on the blockade and international media focusing attention on Akwesasne, Mohawk Ernest Benedict (a seasoned newspaper editor) and several other activists saw an opportunity to promote such events in print through Native channels.14 The first editions of the paper documented the bridge protest extensively, but soon its coverage expanded to news about Native life across Turtle Island and eventually the world. Articles and imagery in Notes frequently drew from history to remind the US and Canadian governments of Native sovereignty over knowledge, identity, land, and education. They did so by emphasizing connections between past atrocities and present politics, providing language lessons, publishing contemporary Native poetry, and documenting oral histories, all while offering a galvanizing outlet of information about contemporaneous Indigenous struggles and victories. Therefore, temporal enmeshment, as a methodology of decolonial resistance, was integral for the entire publication.

Notes was funded through mutual aid—whatever readers could give made up its publishing costs. While a revolving set of individuals edited and contributed to the newspaper routinely, the publishing and distribution of each issue was decisively a communal project, as evidenced by a 1971 editorial: “Four cartons of materials were sifted down to make this issue on a table in Mike Boot’s barbershop. Soon others will come in for the two-day task of putting on labels and wrapping for mailing with the help of grandmas and teenagers and our Mohawk people. It is a community project, with time out from daily chores, preparing for the Maple Festival and the Dead Feast later this month.”15 The intergenerational power behind the construction of Notes reflects the temporal layering of the images and articles presented in the newspaper. While Notes had correspondents and in-house writers and artists, many of its articles and graphics were handpicked from national and international newspapers that happened to run stories about Native life. Crowdsourcing news clippings from readers helped Notes editors curate its content for the convenience of their largely Native audience, which wanted to be kept informed on Indigenous issues.16 These clippings formed the newspaper’s titular “notes,” which were largely about the present but often recited Indigenous histories with the intent of building a better future for all Native peoples.

Relationality and “the Otherwise”

Notes’ posters must be seen in the context of developing postmodern tactics that similarly challenged the social, economic, and political status quo of the 1960s and 1970s by transforming the original intent of images.17 However, while Notes was organized by cosmopolitan editors and designers who took inspiration from several contemporaneous radical movements, it is also important to recognize that notions of communal learning and work, the manipulation of preexisting imagery and stories, the acceptance of change or flux, and the cyclicality of time are not new concepts in Native North American epistemologies.18 Regarding these transformative tropes found in Indigenous oral histories, Carcross/Tagish Native and scholar Candice Hopkins writes:

In art, since the dawn of mechanical reproduction, the copy is understood as subversive: Its very presence . . . challenges the authority of the original. Replication in storytelling, by contrast, is positive and necessary. It is through change that stories and, in turn, traditions are kept alive and remain relevant.19

Notes’ manipulation of preexisting images with text to construct their posters is an extension of established Indigenous knowledge and education.20 Alex Jacobs, a Mohawk editor and graphic artist at Notes, remembers that the ideas of “continuum” and “circular” time were central to the editorial team’s thinking because these notions are autochthonous to Haudenosaunee culture: “When you tell a story . . . there is always a beginning point, but the story often circles back on itself. . . . The creation myths and migration myths—they always come back around—now they are not ‘myths,’ now they are considered Indigenous knowledge.”21 Notes staff understood that text aided Indigenous storytelling and could be a powerful addition to portraits of Indigenous people by white photographers, somewhat anticipating Vizenor’s argument that such images “are never worth the absence of narratives because languages are imagination and photographs are the simulations of culture and closure.”22 The newspaper’s reformatted images, as well as its collecting and reprinting of news stories about Native people, drew from a legacy of transformations and visual puns commonly found in Native imagination and knowledge—that is, in Indigenous design, oral traditions, memories, and art—to create uninterrupted or cyclical trajectories of resistance.

Brascoupe recalls that creating the posters was a group effort. Layout artists and editors, most of whom were Mohawk volunteers, first chose a timely political issue they wished to promote. Then, as a group, they looked over images and texts to brainstorm an effective didactic combination. Jacobs recounts how one of the posters came to be:

A supporter in the Hudson River Valley donated a trove of Edward S. Curtis prints to us. . . . [W]e were always matching quotes from Native peoples with art we made, photos we collected, much of it donated by artists wanting to be supportive. We kept the center spread of the NOTES open for poster ideas and poetry with art. When we travelled around Indian Country we would see the newsprint posters and the $1 posters everywhere.23

Anthropologist and design theorist Arturo Escobar suggests that decolonial design breaks from coloniality’s agenda to separate Indigenous communities by creating cooperative artistic processes and opportunities to imagine “worlds otherwise.”24 Utilizing cooperative, community-oriented processes of making, Notes staff created posters that rekindled the past—or circled back to it—in order to gesture toward “the otherwise,” a possible decolonial future gestating in the present.

Temporal enmeshment aids Indigenous relationality. Brascoupe remembers Hunter’s image with affection because it reminded him of his grandmother, who also enjoyed smoking a pipe.25 Jacobs discusses the poster with similar tenderness:

It represented grandfather and grandmother at the end of the day smoking a pipe. That was the use of tobacco. It is contemplative and meditative. The sun is going down and there is a rocking chair with someone’s grandmother and all you see is an ember from a pipe. It is a common image everyone has. Same thing with my grandmother.26

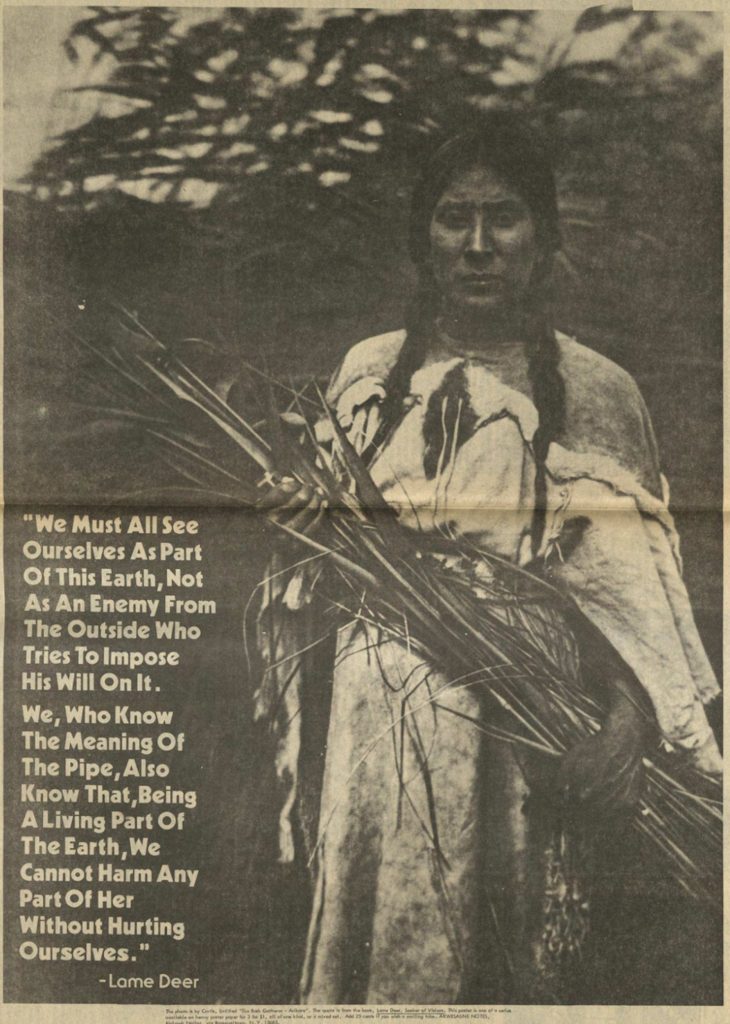

Notes’ communal design and editing process and shared creation of imagery breaks from colonialism’s aspiration to isolate Native individuals from their pasts, futures, and one another—something nineteenth- and early twentieth-century portraits of Indigenous peoples by white settlers did visually. The recontextualized portraits in the Notes collage poster series not only transformed their white makers’ original intent into a more holistic, Indigenous, community-grounded mode of representation, but they also expanded these objects’ relationship to land/place, identity, and time. For instance, Edward Curtis’s 1908 photogravure titled The Rush Gatherer—Arikara depicts an Arikara woman clad in a hide dress, standing by herself against a backdrop of tall rushes (fig. 5). Her hands are wrapped around a bushel likely chosen for mat-making purposes. Like many turn-of-the-century portraits of Native women by white men, she is shown isolated in nature and appears historically bound. By placing her in proximity to a superimposed quote from Sioux medicine man Lame Deer, however, she is transformed: “We Must All See Ourselves As Part Of This Earth, Not As An Enemy From The Outside Who Tries To Impose His Will On It . . .” (fig. 6). This simple restructuring restores her power and agency and points to her as custodian of the land in which she is posing. The quote’s emphasis on the word “we” also underlines the poster’s collectivizing intent, which supported contemporary activists’ ongoing efforts to create pan-Indigenous solidarity throughout the 1970s. In visualizing and inspiring relationality between all Native people, past and present, the creators of Notes diverted the liberating notion of possibility, or “the otherwise,” into Native hands and prevented coloniality’s dissolution of Indigenous futures.

Visual Sovereignty

In her study on the way Indigenous filmmakers reconfigure and challenge ethnographic film conventions to maintain Indigenous epistemologies and a connection to land, Michelle H. Raheja conceptualizes the phrase “visual sovereignty” as a notion that can enhance our understanding of how temporal enmeshment functioned in the Notes posters. According to Raheja, Indigenous-made films deploy visual sovereignty by communicating knowledge about important issues such as “land rights, language acquisition, and preservation,” as well as other issues relevant “to a mass, intergenerational, and transnational indigenous audience.”27 These are features plainly found in the selection of articles and images in Notes. Raheja further explains, however, that “visual sovereignty, as expressed by indigenous filmmakers, also involves employing editing technologies that permit filmmakers to stage performances of oral narrative and indigenous notions of time and space that are not possible through print alone.”28 I would nuance this claim by adding that the Notes posters collapse time and history to assert visual sovereignty in a way similar to film. While the posters do not have the same capacity to create cinematic temporal dynamics, their claiming, editing, and remaking of Indigenous portraits and words across time not only engage with and deconstruct settler-generated portrayals of Indigenous people, but they also assert Indigenous sovereignty temporally (because they regenerate the past as present activists fight for Indigenous futures) and spatially (because they largely concern the liberation of land).

For example, The Shrine of Hypocrisy depicts a formerly commodified image of an ancestor to promote Native sovereignty over land, lifeways, and time. By reusing the iconic portraits and the words of historical Indigenous resistance fighters, Notes encouraged Native rights organizations’ ongoing efforts. The paper reported on all of AIM’s most important demonstrations. Because of Notes’ affiliation with traveling educational unity groups, like White Roots of Peace and those led by Akwesasne teacher Ray Fadden, the paper was trusted by, and had exclusive access to, Native rights leaders such as Russell Means Dennis Banks and Akwesasne’s own Richard Oakes. Native activists’ marches, protests, and demonstrations, particularly the occupations of Mount Rushmore in 1971 and Wounded Knee in 1973, were undoubtedly fresh in the minds of all who saw The Shrine of Hypocrisy poster published by Notes around the US bicentennial in 1976. Leaders like Sitting Bull and Old Chief Joseph—not to mention the very presence of a dynamic newspaper like Notes reporting on AIM’s actions—dismiss the idea that survival and resistance ever stopped after Native peoples were confined on reservations.

The Shrine of Hypocrisy encapsulates Jarrett Martineau and Eric Ritskes’s assertion that “Indigenous art contributes to decolonization by disrupting colonialism’s linear ordering of the world and its conditioning of possibility.”29 This disruption is achieved “by Indigenous remembrance and re-presencing on the land.”30 Without intervention from Indigenous people, historical portraits of Natives by non-native artists struggle to accomplish this task. Visenor writes extensively about the simulation of the “Indian” present in such archival photographs—images that primarily serve to suggest the “absence of Native memories and the actual landscape.”31 Significantly, in The Shrine of Hypocrisy, Sitting Bull’s face appears to occupy the space behind Roosevelt’s head, a place on the mountain where a ceremonial altar had been erected during the 1971 Mount Rushmore protest. By reviving and reintegrating Sitting Bull into the actual contested landscape, the Notes designers released him from his pose-locked image, asserted Native stories and connections to the land, and supported ongoing struggles for sovereignty.

Notes’ Impact

Since contemporary Native lives are so impacted by histories too often misremembered or ignored by settler culture, Indigenous peoples often fight this historical amnesia by forcing a process of remembering on viewers and readers. For Notes, this process involved not just remembering but reactivating important Indigenous ancestors. The paper’s staff took part, then, in a process eloquently described by Achille Mbembe in “The Power of the Archive and Its Limits”:

Writing history involves manipulating the archives. . . . Following tracks, putting back together scraps and debris, and reassembling remains, is to be implicated in a ritual which results in the resuscitation of life, in bringing the dead back to life by reintegrating them in the cycle of time, in such a way that they find, in a text, in an artefact or in a monument, a place to inhabit, from where they may continue to express themselves.32

While themes of transformation, cyclical time, and ancestral or spectral guidance have existed in Indigenous oral and visual traditions for thousands of years, Notes’ mobilization of these tropes through the means of temporal enmeshment contributed to the development of contemporary decolonial media in an important way.

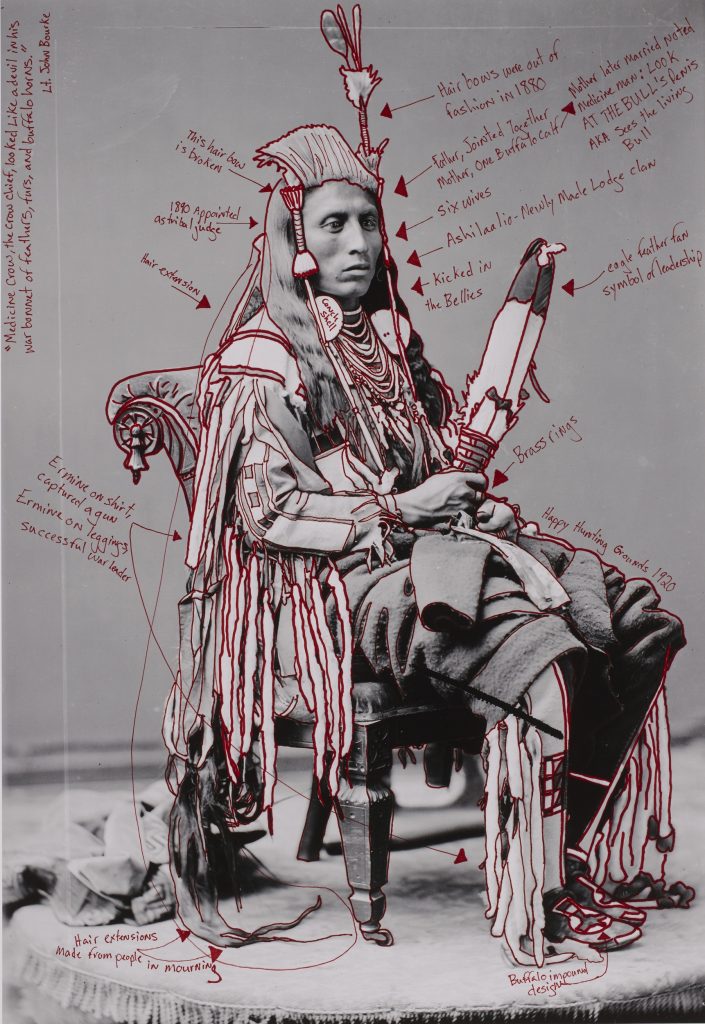

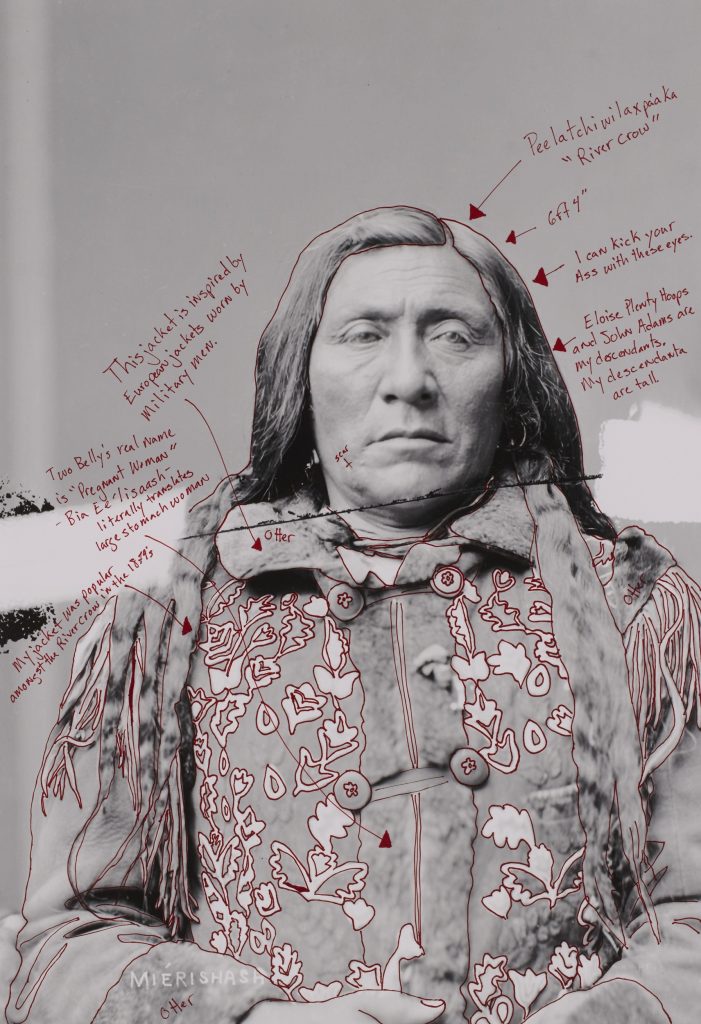

Notes’ deployment of temporal enmeshment is reflected in the work of numerous contemporary Indigenous artists and designers who also mine archives for Native portraits to dehistoricize the past and free Native identity from settler optics. For example, in Red Star’s series 1880 Crow Peace Delegation, the artist annotates several portraits of Medicine Crow and other members of the peace delegation taken by the white photographer Bell in Washington, DC (fig. 7). These Indigenous leaders traveled some two thousand miles to advocate for their people and negotiate terms with the US government. While the men were highly regarded in their own communities, their portraits were deposited at the Bureau of Ethnology, a governmental department that systematically documented Indigenous peoples before their assumed extinction.33 Once categorized, each delegate’s individuality was thus muted and controlled. The subsequent dissemination and appropriation of these images—found, for instance, on contemporary packaging for the Coca-Cola Company Honest Tea’s “First Nation” range of organic iced teas—further obstructed the sitters’ identities.34 Nefarious ideologies are also evident in the profile view used for many of the portraits, which was a popular method deployed by physiognomists and phrenologists to showcase racialized features.35 By annotating the photographs with text, Red Star literally gives these individuals their names back. Each annotation is done in bright-red pen and works to humanize the sitter while highlighting the luxurious materials that adorn their regalia, the origin and meanings of which were likely unknown to Bell and most non-native viewers. The sentiment behind each annotation ranges from humorous, to poignant, to valiant. Two of Bia Eélisaash (Two Belly)’s annotations read, “I can kick your ass with these eyes” and “Eloise Plenty Hoops and John Adams are my descendants. My descendants are tall” (fig. 8). By mentioning a physical attribute of living relatives and strategically using present tense in the notation with “I can,” Red Star ensures that Two Belly is not only an important ancestor to someone living but that his personhood may persist in the here and now. Time is depicted as enmeshed in Red Star’s images because Two Belly, Medicine Crow, and the other delegates are not simply being remembered; rather, they appear to continue to express themselves in the present through Red Star’s annotations. The delegates are no longer controlled by the bounds of history in which the colonizer defined them.

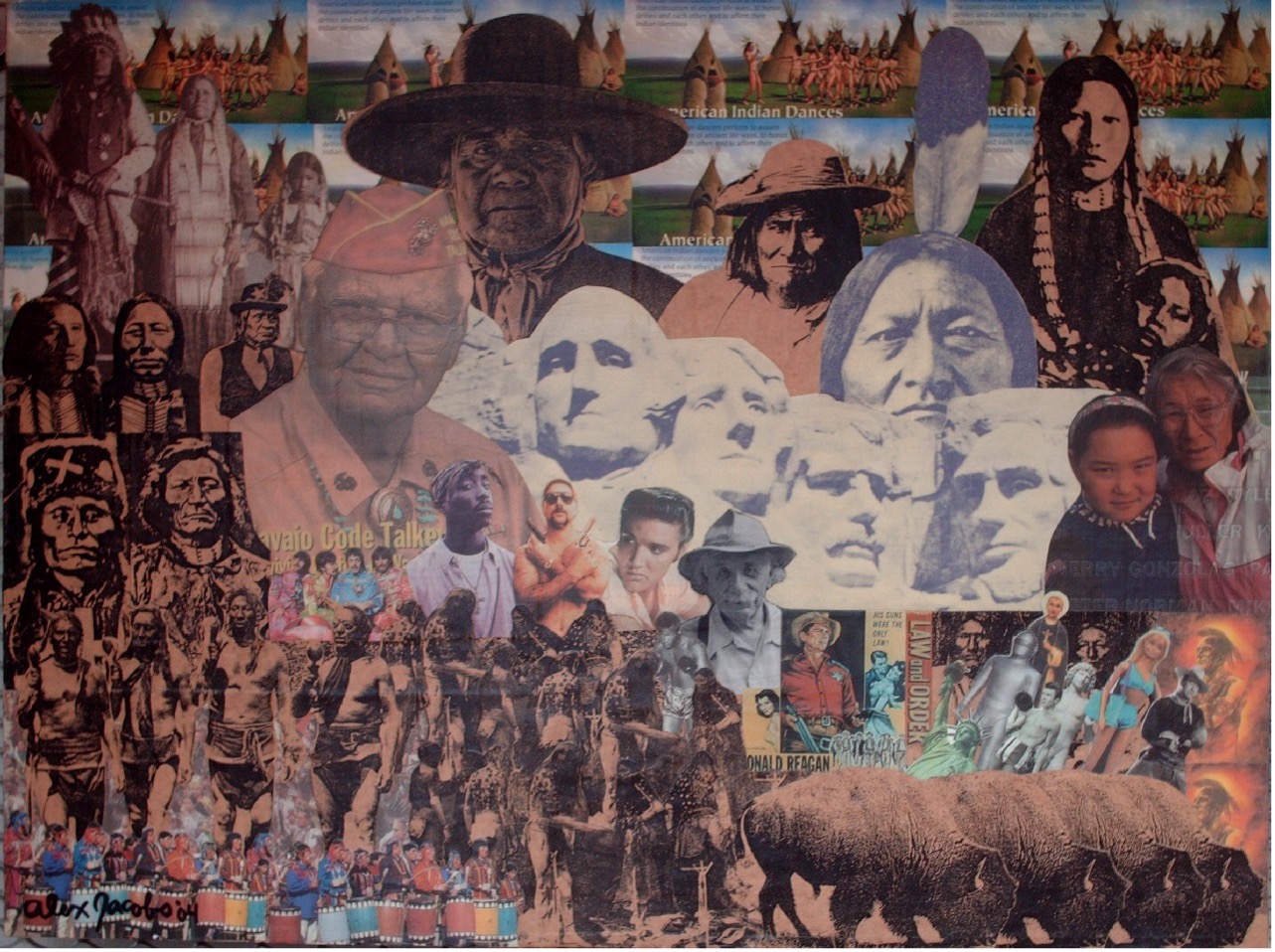

When Jacobs was asked where he sees Notes’ influence today, he responded that Notes started the trend of “appropriating from the appropriators. . . . [I]t circles back around. It’s called ‘meme warfare’ now. And with young artists today, I see Notes in a whole new generation. I still use things Notes published in my art.”36 Jacobs’s own collage work is an intense cacophony of temporal moments represented through mass-media images spliced with historical photographs. The Shrine of Hypocrisy makes an appearance in several of his paper collages. In HEROES, Sitting Bull gazes back amid other images that include pictures of real Indigenous “heroes,” obscure pop-culture headlines, a blonde Barbie in a bikini, stills from Hollywood Westerns, and other representations of false Indigenous imagery (fig. 9).

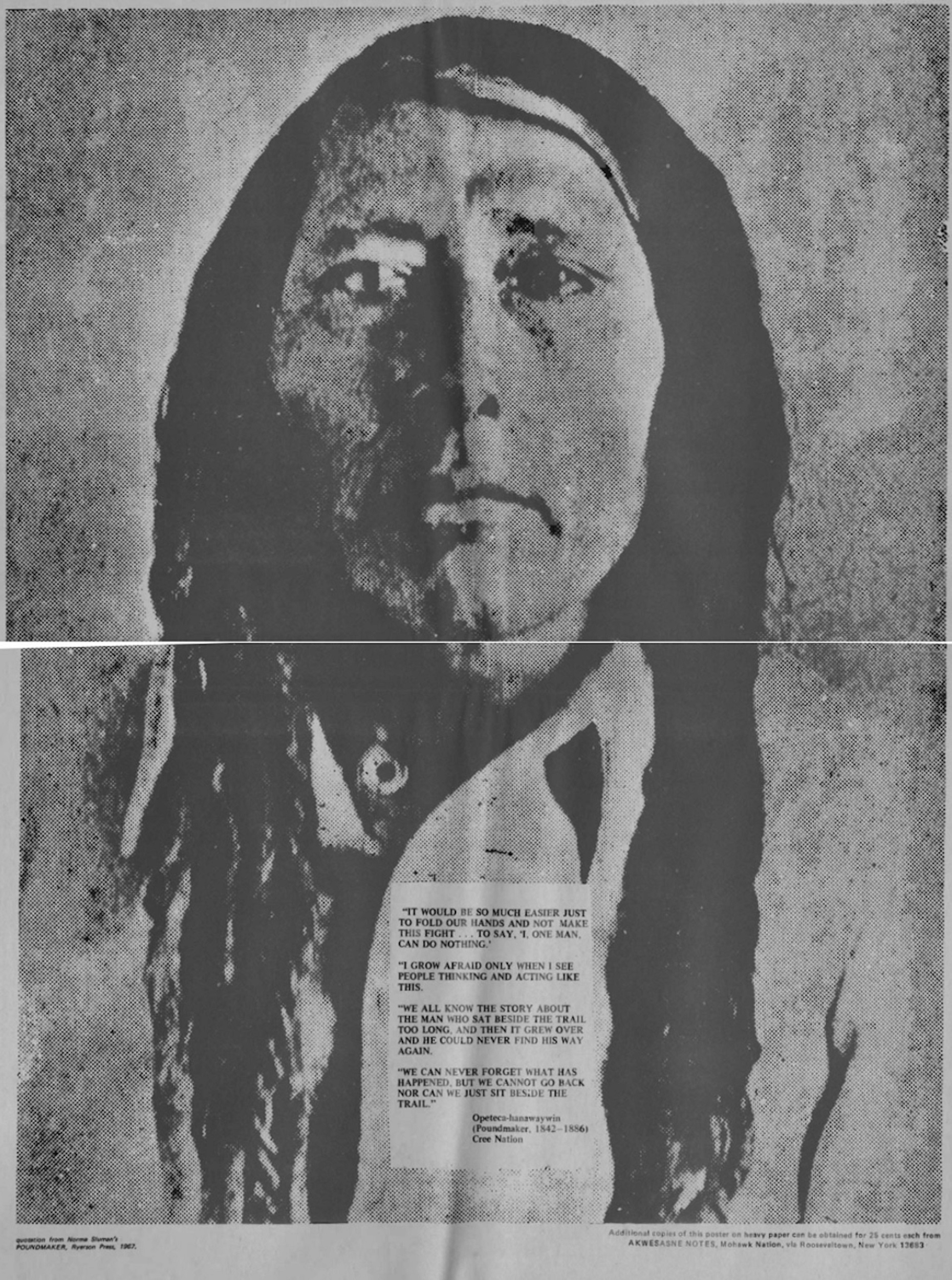

A poster published by Notes in 1971 features an image and words attributed to the Cree chief Poundmaker (fig. 10). The poster urges its viewers/readers to avoid apathy and continue their fight for sovereignty: “We all know the story about the man who sat beside the trail too long . . . it grew over and he could never find his way again. We can never forget what has happened, but we cannot go back nor can we just sit beside the trail.”37 Not many viewers are aware that the iconic nineteenth-century image of Poundmaker featured by Notes is ostensibly his mug shot, taken when he was outrageously placed into the Stony Mountain Penitentiary in Manitoba after he led his people peacefully through the North-West Rebellion.38 Poundmaker became ill while imprisoned and died not long after his release. By placing him within a context completely opposed to the photograph’s origins, the Notes poster visually frees and revives Poundmaker from both incarceration and death at the hands of his colonizers, so that he could continue instructing his living relatives.

Through the poster, the newspaper’s staff demonstrates that decolonization is a process that must involve remembrance but is not passive; it is active and future-minded. Indigenous makers past, present, and future had to and will continue to have to contend with the inventive settler whose created memories tend to become history, but Notes blew open the fissures of these histories and engendered revolutionary, alternative ways of seeing and remembering, of social activation, and of Indigenous solidarity. The consequences of such actions on the colonial project, especially regarding imperial assumptions about linear time and the progression of history within the doctrine of Manifest Destiny, is profound and liberatingly destructive.

Remembering Notes and its achievements perpetuates its breakthroughs and decolonial efforts in our present. Decolonization is a long, ongoing process that involves the liberation of land and minds from colonial power. Part of this work, as Notes’ posters show, involves the process of remembering. In the spirit of active remembrance, much more work beyond this article needs to be completed to fully recognize the newspaper’s contributions to decolonial media aesthetics, counterculture history, and Indigenous liberation movements of the 1970s and beyond. I encourage the readers of this article to take part.

Cite this article: Margaret J. Schmitz, “Indigenous Temporal Enmeshment in Akwesasne Notes,” in “About Time: Temporality in American Art and Visual Culture,” In the Round, ed. Hélène Valance and Tatsiana Zhurauliova, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 8, no. 2 (Fall 2022), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.15034.

Notes

- In issues of Notes, Alex Jacob’s Mohawk name was credited and spelled as Karoniaktatie. ↵

- Mark Rifkin, Beyond Settler Time: Temporal Sovereignty and Indigenous Self-Determination (London: Duke University Press, 2017), 131, 135. ↵

- Henrietta Lidchi and Hulleah J. Tsinhnahjinnie, eds., Visual Currencies: Reflections on Native Photography (Edinburgh: National Museums Scotland, 2009), xviii. ↵

- Ariella Aïsha Azoulay, Potential History: Unlearning Imperialism (London: Verso, 2019). ↵

- The paper’s circulation skyrocketed from 10,000 its first year to 150,000 within eight years. Doug George-Kanentiio, “Akwesasne Notes: How the Mohawk Nation Created a Newspaper and Shaped Contemporary Native America,” in Insider Histories of the Vietnam Era Underground Press, ed. Ken Wachsberger (East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 2011), 127. ↵

- An important exception is Louise Siddons’s excellent article investigating the coalition of the Black Panthers and AIM activists around the 1973 occupation of Wounded Knee—and their resulting liberation aesthetics—which includes discussions about Notes: Louise Siddons, “Red Power in the Black Panther: Radical Imagination and Intersectional Resistance at Wounded Knee,” American Art 35, no. 2 (Summer 2021): 2–31. ↵

- Gerald Visenor, Fugitive Poses: Native American Indian Scenes of Absence and Presence (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1998), 146. ↵

- Jill Sweet, quoted in Morgan Bell, “Some Thoughts on ‘Taking’ Pictures: Imaging ‘Indians’ and the Counter-Narratives of Visual Sovereignty,” Great Plains Quarterly 31, no. 2 (Spring 2011): 90. ↵

- Jolene Rickard, quoted in Bell, “Some Thoughts on ‘Taking’ Pictures,” 90. ↵

- Clayton Brascoupe, interview with the author, August 10, 2022. ↵

- Wendy Red Star and Shannon Vittoria, “Apsáalooke Bacheeítuuk in Washington, DC: A Case Study in Re-Reading Nineteenth-Century Delegation Photography,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 6, no. 2 (Fall 2020), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839 .10672. ↵

- Eve Tuck and C. Ree, “A Glossary of Haunting,” Handbook of Autoethnography, ed. Stacey Holman Jones, Tony E. Adams, and Carolyn Ellis (Newbury Park, CA: SAGE, 2013), 642. ↵

- George-Kanentiio, “Akwesasne Notes,” 109–38. ↵

- For more information on the 1969 customs dispute, see National Film Board, “You are on Indian Land,” YouTube video, 36:44, 1969, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=URpZwAuvxjQ&ab_channel=NFB. Leaders at the first Notes meeting included Ernest Benedict, Tom Porter, John Fadden, Mike Boots, Mose David, Iran Benedict, Alec Gray, Mary Tebo, and Anne Jock. See George-Kanentiio, “Akwesasne Notes,” 126. ↵

- Editorial, Akwesasne Notes 3, no. 2 (1971): 3. ↵

- In addition, like several other underground newspapers at the time, Notes contributed to, and made use of, the Liberation News Service, which provided packets of news stories, clippings, and images for radical periodicals to reprint. ↵

- Notes’s rerouting of historic portraiture is likely informed by, for instance, the Situationists’ detournement tactic made popular among counterculture activists since the 1950s. On occasion, the Black Panther also reproduced manipulated nineteenth-century portraits to extend solidarity to Native people in the early 1970s—but these works were also very likely influenced by Notes’ output. See, for example, Malik Edwards, Untitled (Chief Joseph), Black Panther, March 31,1973; Siddons, “Red Power in the Black Panther,” 20. ↵

- Brascoupe recalls that he and his colleagues had regular access to various underground publications at the time, including from journals and newspapers published by the Black Panthers, the Chicano movement, lesbian and gay rights movements, and even comics, like Zap Comix (interview). ↵

- Candice Hopkins, “Making Things Our Own: The Indigenous Aesthetic in Digital Storytelling,” Leonardo 39, no. 4 (2006): 342. ↵

- For more contemporary examples of this tactic, see Karen Ohnesorge, “Uneasy Terrain: Image, Text, Landscape, and Contemporary Indigenous Artists in the United States,” American Indian Quarterly 32, no.1 (Winter 2008): 43–69. ↵

- Alex Jacobs/ Karoniaktahke, interview with the author, August 16, 2022. ↵

- Visenor, “Fugitive Poses,” 157. ↵

- Jacobs quoted in “Classic ’70s Poster Art: Akwesasne Notes x Edward S. Curtis,” Indian Country Today, July 17, 2014, https://indiancountrytoday.com/archive/classic-70s-poster-art-akwesasne-notes-x-edward-s-curtis. ↵

- Arturo Escobar, “Worlds and Knowledges Otherwise,” Cultural Studies 21, nos. 2–3 (2007): 179–210. ↵

- Brascoupe interview. ↵

- Jacobs/ Karoniaktahke interview. ↵

- Michelle H. Raheja, “Reading Nanook’s Smile: Visual Sovereignty, Indigenous Revisions of Ethnography, and ‘Atanarjuat (The Fast Runner),’” American Quarterly 59, no. 4 (2007): 1162–63. ↵

- Raheja, “Reading Nanook’s Smile.” ↵

- Jarrett Martineau and Eric Ritskes, “Fugitive Indigeneity: Reclaiming the Terrain of Decolonial Struggle through Indigenous Art,” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society 3, no. 1 (2014): v. ↵

- Martineau and Ritskes, “Fugitive Indigeneity.” ↵

- Visenor, “Fugitive Poses,” 152. ↵

- Achille Mbembe, “The Power of the Archive and Its Limits,” in Refiguring the Archive, ed. Carolyn Hamilton et al. (Dordrecht: Kluwer, 2002), 25. ↵

- Red Star and Vittoria, “Apsáalooke Bacheeítuuk in Washington, DC.” ↵

- Red Star and Vittoria, “Apsáalooke Bacheeítuuk in Washington, DC.” ↵

- Bell, “Some Thoughts on ‘Taking’ Pictures,” 87. ↵

- Jacobs/ Karoniaktahke interview. ↵

- The first time this quote and image were published in Notes was vol. 3, no. 7 (1971), but the formatting diverged from what was ultimately advertised later in Notes and sold via mail order. A version of the latter can be found at the Oakland Museum of California, http://collections.museumca.org/?q=collection-item/20105410034. ↵

- The 1885 photograph can be found in the Glenbow Museum archives, where its origin is listed as Stony Mountain Penitentiary. ↵

About the Author(s): Margaret J. Schmitz is Assistant Professor in the Department of Art History at the Milwaukee Institute of Art and Design.