José María Mora and the Migrant Surround in American Portrait Photography

The brief, bright career of the Cuban-born, US photographer José María Mora (1847–1926) represents a passage in American photography that deserves re-reading—in part because the vivid artifice of his work defies conventional expectations for how photographic images operate as cultural texts. Traditionally, historical narratives of photography in the United States have centered on the artistic pursuit of representational reality. Foundational scholarship in the field, seeking to define the characteristics of a national practice, identified the unembellished style of daguerreotypes, survey photos, and fledgling photojournalism with a distinctly American sensibility that was perceived as pragmatic, socially minded, and seemingly straightforward in its presentation of factual detail.1 These aesthetic qualities mapped neatly upon a prevailing desire to understand photographic images as illustrations of history. Robert Taft, for instance, in his pioneering 1938 study Photography and the American Scene, presented the medium’s formal development as a direct outgrowth of social events, describing his scholarly method in similar terms, as arising from an “accumulation of facts” about the technical evolution of image-making in the United States.2 Fifty years later, with the landmark publication of Reading American Photographs in 1989, Alan Trachtenberg proposed a more nuanced approach to photography’s beguiling realisms. Tracing the lineage from Mathew Brady’s grim Albums of War to Walker Evans’s “documentary style” masterpieces for the Works Progress Administration, Trachtenberg demonstrated that the process of framing and naming a view was fundamentally a political act, meaning that photography, like history writing, was less a process of accumulating facts than searching and selecting from a vast field of possibility to compose subjective patterns of meaning. As he wrote, “What empowers an image to represent history is not just what it shows but the struggle for meaning we undergo before it.”3 It is not only photographic subject matter, then, but also how that subject matter is approached that shapes the perceived relationship between photographs and history. From this perspective, as he asserted, “the viewfinder is a political instrument” for photographer and historian alike, with photographic images operating as sites through which past and present stakeholders manage and manufacture meaning about cultural experience in the United States.4

Yet if Reading American Photographs broke new ground in articulating the complex interrelationship of photography and history, it was less concerned with expanding the borders around what constituted “American” photography, or of challenging the primacy of a documentary style as the visual language through which cultural experience was most readily expressed. For Trachtenberg, this tightly focused aesthetic selection was purposeful in demonstrating how elements of subjectivity resided even in those images that appear least likely to contain it, but the possibility of locating a characteristic national vision nonetheless remained central to his interest.5 He concluded, even as we read photographs as complex cultural texts, that “it is not so much a new but a clarifying light American photographs shed upon American reality.”6 The difficulty with this perspective, and the canon developed to support it, is that it implies the existence of a singular “American reality” that might be read into and through historical images—and encourages us to search for its expression in a visual language that positions the photographer as cultural insider playing witness to history. This possibility is complicated by the urgent necessity of acknowledging that the mechanisms for framing the rules of representation have been accessible only to a privileged few for much of US history, so the scholarly valorization of representational reality may paradoxically limit full understanding of the medium’s true diversity of early use.

Re-reading American photographs with these politics of visuality in mind demands radically expanding the conventional range of this historical viewfinder. This involves not only embracing underrepresented subjects (though this too is crucial), but also reappraising those images, makers, and stylistic approaches that have proved an uncomfortable fit with enduring scholarly narratives—reevaluating how overlooked contributions to the annals of photographic history may illuminate more inclusive terms of engagement in the struggle for meaning through which we visualize the rich diversity of cultural realities that have shaped the United States.

Re-Reading the Unreal

Devoting renewed attention to photographers like Mora, who have been long excluded from scholarly consideration for seeming to traffic in the unreal, demonstrates how developing alternate modes of interpretive literacy can bring multicultural American experience into sharper focus. Based in New York City, Mora rose to national prominence during the 1870s and 1880s. He followed in the stylistic footsteps of his mentor Napoleon Sarony to build a phenomenally successful business by crafting elaborately staged celebrity portraits that circulated as cabinet card photographs—mounted 4 1/4 x 6 1/2-inch albumen paper prints that were avidly collected by a growing consumer class.7

The cabinet card was introduced in 1866 as part of a calculated effort to reinvigorate the US photographic business, which had started to flag with the close of the Civil War. Industry leaders such as Edward L. Wilson suggested that providing consumers with a novel image format would encourage them to refresh their portrait collections and generate fresh demand for the larger-sized albums and frames needed to display them.8 What Wilson and others did not anticipate, however, was the way this change would also revolutionize the medium’s aesthetic possibilities. With nearly twice the surface area of the tiny 2 x 3-inch cartes-de-visite images that had preceded them, cabinet cards brought new attention to compositional elements such as background, pose, and props simply by making them more visible. As a result, the final three decades of the nineteenth century were a golden age for staged studio portraiture, as rival photographers sought to outdo one another by orchestrating elaborate portrait settings crowded with prop furniture, papier-mâché rocks, and artificial trees.9

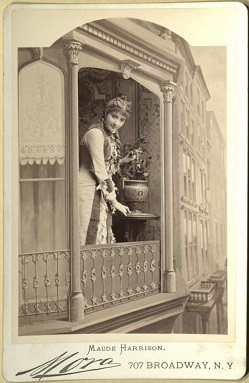

Mora developed a special reputation within this competitive commercial field as the unrivaled master of the studio backdrop. Many of his contemporaries employed these oversized painted renderings of landscapes or interiors as decorative elements in their portraits, but not always to equal degrees of success. Examples abound of awkwardly posed cabinet cards that depict subjects standing stiffly before flat canvas scrims, appearing strangely detached from the pictorial spaces that are supposed to contain them.10 What distinguished Mora’s portrait work was his ability to craft persuasive illusions that immersed sitters within utterly fantastical surroundings. Using multiple-plate exposures, retouching, and custom-designed set pieces, he transported his subjects beyond the mundane reality of the studio so that they convincingly appeared to inhabit the imaginative architecture in a realm of photographic invention (fig. 1). Mora’s knack for bending reality lent his work broad popular appeal and a mobility of purpose that echoed, to some degree, the spatial fluidity of his approach. He was the portraitist of choice for the Metropolitan Opera and Manhattan’s high-society costume balls, so during the 1870s and 1880s elite performers and socialites flocked to his studio to see themselves re-envisioned through his camera lens. At the same time, his photographs of comic actors, burlesque dancers, and clowns appeared as reproductions in the tatty tabloid pages of the National Police Gazette, giving his work unusual visibility across social and media hierarchies at a time in US public culture when these borderlines were growing increasingly rigid.

Despite Mora’s prominence and evident ambition, the characteristic artifice of his work has prompted it to be dismissed as a relic of Gilded Age consumer taste rather than valued as a meaningful cultural text. Taft devoted a chapter of Photography and the American Scene to Mora, Sarony, and their contemporary William Kurtz, identifying these artists as exemplars of what he derisively termed the “elaborate style” portraiture that dominated US photographic practice following the Civil War.11 In his view, the dramatic poses, theatrical settings, and props employed in these artists’ studios were analogous to other “grotesque” manifestations of Gilded Age taste—fashions such as bustles, hoopskirts, and exaggerated Lord Dundreary side-whiskers. In addition to discouraging deeper consideration of these photographers’ work, this logic allowed Taft to frame the dramatic artifice of cabinet cards as little more than a temporary aberration from the usual course of American photographic realism. He concluded that by setting a portrait against a wall of imitation stone, in a room filled with mock furniture, or on the banks of an artificial river, the late nineteenth-century American photographer “was but reflecting the day in which he lived” by replicating the shoddy material abundance of a postwar economic boom.12 Later scholars followed suit by aligning late nineteenth-century photography with US consumer habits and misguided mimicry of painting—the type of machine-made Victorian excess from which the purer forms of modernism would ultimately emerge.13

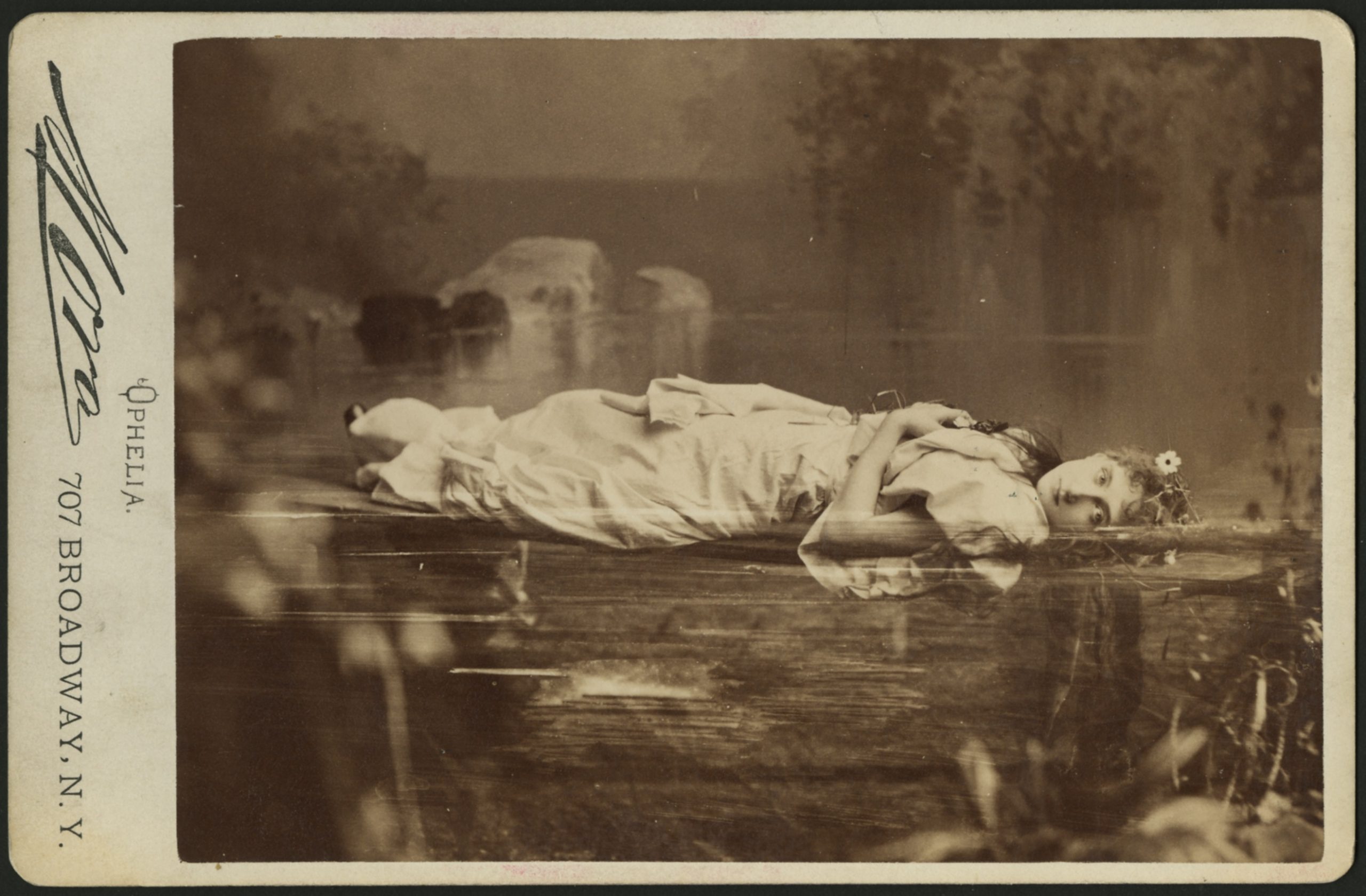

Yet Mora’s artistic compositions demand greater attention—a more careful read—because their labor-intensive production and complex spatial manipulations go so far beyond the necessity of their superficial commercial purpose. His portrait of the popular actress Maud Branscombe as Ophelia offers a fitting example of his approach (fig. 2). The image casts Branscombe as tragic heroine of Shakespeare’s Hamlet floating in a river immediately prior to her death by drowning. Mad with grief over the recent loss of her father, Ophelia is gathering flowers on the banks of a river when she slips and falls into the water. In the play, the scene occurs offstage. After the fact, Queen Gertrude describes how Ophelia’s long skirts kept her temporarily afloat but ultimately made it impossible to save herself. “Her clothes spread wide/And, mermaid-like, awhile they bore her up,” until “heavy with drink” the waterlogged garments pulled her down “to muddy death.”14 Perhaps inspired by well-known artworks like Sir John Everett Millais’s painting of the same subject (Ophelia, 1851–52; Tate Gallery), Mora’s photograph makes this extratextual tragedy visible by depicting Branscombe suspended in the moment between life and her inevitable demise as she begins to sink beneath the surface of the waters.

To produce such an image using the photographic technologies of the 1870s was a massive creative undertaking. Slow exposure times and the limited focal range of period portrait cameras would have made working outdoors to stage the scene in a natural setting absolutely impracticable. Under the circumstances, Mora’s best available option was to manufacture every visible element of the picture (apart from Branscombe herself) in the controlled environment of his studio. The resulting mixed-media image is at once obviously artificial and difficult to reverse engineer, a visual puzzle that engages what Neil Harris termed the “operational aesthetic” in a way that no doubt fueled the popular appeal of Mora’s photography with its original audience.15 A painted backdrop of rocks and foliage defines the distant landscape, while the foreground of the picture has been manipulated to disguise the studio where the actress posed. This seam between imagination and reality is concealed within an atmospheric blur of rippling currents and water plants produced using double exposure, composite printing, and hand-painted retouching.

The visual dramatics staged by Mora in his studio stood apart from any coincident theatrical production. Branscombe was known more for her beauty than her acting ability (indeed, scathing period reviews suggest that Shakespeare was far outside her range).16 Although she appeared briefly in a light burlesque variation on Hamlet, which may have created the occasion for Mora’s photograph, there otherwise was likely little relation between her comic stage role and his moody portrait. Indeed, Mora’s painterly manipulations lend her photographed performance an unsettling edge. As Branscombe gazes placidly toward the viewer, the portion of her body beneath the surface of the water takes on eerie translucence, and dark tendrils of her hair stream toward the river bottom, making it possible to imagine that in the next moment the mad princess will be dragged down into the depths. This sense of unfolding, narrative temporality within the still image is enhanced by the clashing logic of merged visual media, which imbues the image with a peculiar sense of spatial dislocation as photographic realism simultaneously undermines and supports the viewer’s ability to make believe in the picture’s verity.

In addition to underestimating the complexity of such reality effects, what Taft and others have largely overlooked is that Mora and the other so-called elaborate-style photographers were recent immigrants to the United States as, most likely, were the majority of their clientele during these peak decades of late nineteenth-century global migration. Re-reading Mora’s photography within this framework further challenges conventional interpretation of its unreality as a symptom of period consumer culture by illuminating an expanded picture of how publicly circulated portraiture participated in the formation of national identity for millions of new arrivals to the United States.

For Mora, as a recent Cuban exile, I propose that the theatrical fluidity of Gilded Age portraiture served special creative purpose in representing the shifting sense of place that characterized the forced transience of his American experience. In this sense, the customized theatrical spaces that he conjured in his studio operate as what I call a “migrant surround,” an unfixed site or background against which new social images are invented and performed. Drawing upon T. J. Demos’s concept of the “migrant image,” this notion applies both to the varied material elements of setting and the studio itself. The migrant surround describes the way late nineteenth-century photographic studios functioned as spaces of exception outside of the bounds of normal social performance, where portrait makers and subjects alike might experiment with what Demos calls “self-willed acts of mutability and becoming.”17 From this perspective, the flickering ambiguities of Mora’s visual effects and double exposures might be read not only as willful departures from recognizable reality, but as analogic expressions of a “double frame,” as Homi Bhabha characterized migration, or “double perspective,” as Edward Said described the condition of exile, representing a visual impermanence suggestive of identity at a point of cultural interstices.18 Viewed as realizations of the migrant surround, the shifting sites Mora constructed for his photographs during the peak years of his activity in the 1870s and 1880s represent a struggle to make meaning from a cultural reality that lacked the type of fixed symbols that could be located and easily photographed in the extant physical world. In his portrait of Branscombe (herself an immigrant) as Ophelia, the photographic image drifts from the shore of recognizable documentation in a temporal and spatial suspension of visible reality that nonetheless captures something real.

Locating the Migrant Surround

The son of wealthy Cuban landowners, Mora’s relocation to New York City was abrupt and not wholly voluntary. He was living in Paris and training as a painter in 1868 when his family was suddenly forced to flee their home in Havana with the start of the Ten Years’ War. Mora’s father, José María Sr., and his uncles, Manuel and Antonio Maximo Mora, were co-owners of one of the island’s largest sugarcane plantations. As reform-minded members of the Havana elite, they supported the uprising led by Carlos Manuel de Céspedes that launched the island’s violent bid for independence from Spanish colonial rule. After resettling in New York, José María Sr. became a leader of the separatist activism movement that bolstered the ongoing revolution from the United States by securing financial, political, and popular support for the cause of Cuban independence. He helped to draft the Manifesto of the Cuban Junta that was published in newspapers across the United States in January of 1870 and was one of its five signatories, along with Miguel de Aldama, Hilario Cesneros, Francesco Fesser, and J. M. Mestre. This bold open letter addressed “to the American people” laid out the revolutionaries’ goals of political liberty and the abolition of slavery on the island, and sought to combat public messaging from Spain that the Cuban rebellion was losing energy by signaling the strength and resolve of the diasporic community in the United States.19 The Spanish government had already seized the Mora family’s plantation and property in Cuba, but in November of 1870, following the letter’s publication, they sentenced José María, Sr., and Antonio Maximo to death in absentia for their complicity in the rebellion, along with numerous other prominent members of the US-Cuban community.20 The Moras’ wealth and privilege previously had allowed them to travel freely between Manhattan and Havana, attending to business, educating their children and shopping in New York, and even maintaining residences in both cities.21 The threat of execution effectively arrested this easy migration by barring them from ever returning to the island, a fate that loomed large in the minds of the Mora family. Historian Lisandro Pérez has noted that when asked to describe his occupation on the 1870 Census, José María, Sr., chose to respond “Cuban Refugee,” instead of stating his profession as a merchant and investor, as if this “identity had now overtaken him, forged by war and banishment: refugee,” reflecting a lingering sense of loss that reordered other aspects of lived reality.22

Mora’s career as a photographer took shape against this background, and the thread of displacement described by his father runs just beneath the surface of his work. Unable to continue his studies as a painter once he joined his family in New York, Mora approached Napoleon Sarony to be trained in the photographic portrait business. The Sarony studio was a bastion for artistically inclined, recent arrivals to the United States. Sarony himself was a native French speaker born in Québec, and his staff included other Québécois as well as Frenchmen, Brits, and several Cubans. Although Mora became a naturalized US citizen in 1878, just a few years after launching his independent photographic studio, his relationship to this national identity always retained a sense of contingency.23 Cast out of Cuba, perceived as foreign in New York, fugitive from Spain, and financially unable to return to Paris, he spent much of the remainder of his life in a diplomatic limbo between the US State Department and Spanish government. His later years were devoted to a lengthy legal battle to recover compensation for his family’s land, a process that gradually unraveled his portrait business and also, with the outbreak of the Spanish-American War in 1898, his fragile mental health.

The most visible expression of the migrant surround in Mora’s photography was in his vast collection of painted backgrounds. His renown in this area of practice derived in part from the unrivaled selection his studio offered. Where a typical period portrait studio might have two or three painted canvases in regular rotation, Mora stocked more than 150 individual scenes. One visitor observed that the photographer’s collection encompassed “every style of scenery from Egypt to Siberia,” including all imaginable architectural interiors from medieval fortresses to humble cottage kitchens, as well as landscapes depicting plains, mountains, and seascapes—a spectrum of settings that ranged from “tropic luxuriance to polar wastes.”24 Mora designed many of these background scenes himself, presumably drawing upon his early training as a painter, and often working in collaboration with Lafayette W. Seavey, a onetime theatrical agent who developed a lucrative niche position as the Gilded Age photographic industry’s main supplier of prop furniture, scenery, and set-pieces.25

The lavish abundance of Mora’s photographic spaces stood in stark contrast to the spare decor of his studio. Contemporary photographers notoriously packed their reception rooms with a riot of decorative novelties meant to showcase artistic good taste. At Sarony’s, for instance, visitors entered a room bursting with tapestries, taxidermy, and a giant swan-shaped sleigh that once belonged to Peter the Great.26 Mora’s studio, by contrast, was largely empty. Observers described his reception room as plainly furnished with only a few “tastefully mounted” examples of his photographs hanging on dull maroon walls. The so-called operating room, where his photographs were created, was even more stripped down and almost aggressively raw. Its uncarpeted floor was made of rough wood planks, and a disorganized jumble of props was piled haphazardly in one corner. The hundreds of unmounted canvas scrims in Mora’s collection were stored flat against the wall, where staff could lift them out when needed and mount them on a wooden frame and feet (described as resembling “ordinary dovetail bedstead casters”), before positioning them behind a photographic subject.27 This lack of permanent furnishing left his studio a blank, unoriented site that could be made and unmade completely between portrait sessions. Mora’s composition process was equally ephemeral. When constructing a scene, he employed a viewing box devised by the studio’s chief retouching artist, a man named Mr. Costa. The Photographic Exhibitor, as it was called, used a shielded gas jet to project translucent overlays of rippling water, forest foliage, or starry skies into a miniaturized studio space two and a half feet square.28 Mora and his subjects could then view illusive arrangements of sitter, props, and setting before these diverse elements were assembled in the studio and fixed in place by the photograph.

This limitless fluidity of locational possibilities would seem to position the studio as a site for virtual travel, an imaginary recreation of the easy migration his family once enjoyed, and perhaps this was a part of the appeal. But I argue that it was Mora’s creative deployment of these large-scale landscapes that activated the kaleidoscopic potential of the migrant surround. The process of repeatedly constructing a site for photography represented a profound rethinking of the relationship between figure and ground or individual and location, by temporarily unsettling the rigid logic of nineteenth-century connections between location and type. To this point, instead of using his backgrounds in a strictly representational sense, so that their painted content remained legible in the final portrait, he rotated and adjusted the canvas backdrops to suit the composition of his photographs, positioning their light and dark tonalities as abstracted design elements rather than symbolic referents. Two portraits Mora created to mark the occasion of the 1883 Vanderbilt costume ball, for instance, employ the same seascape backdrop, albeit in radically different orientations. In a picture of Alice Vanderbilt as the Spirit of Electricity, the horizon line of a rough sea runs along the left margin of the photograph (fig. 3). Vanderbilt’s body obscures the top of a steep cliff perpendicular to the water, while a trio of seabirds swirls around her raised torch. His portrait of Lizzie Pelham Bend as La Vivandière du Diable (a kind of female Mephistopheles) again uses this seascape backdrop. This time, however, the canvas is positioned upside down so that the water is immediately over the subject’s head, and the flying sea birds are just visible above the feathers in her cap (fig. 4).29 Mora’s creative deformation of the backdrop’s specificity as locational referent demonstrates that his process for setting a photographic scene involved more than matching a subject with an environment where it logically belonged. It was instead migrant in nature—so that the pictured subject oriented the meaning of a depicted background as much as it shaped the identity of the figure. Viewed in this way, a seascape cliff could represent Valhalla or a fiery inferno. It was not the place so much as the people within it that defined the meaning of a given location. Within the type of non-negotiable dislocations that directly shaped the lives of Mora and his family, this reflexive relationship between subject and site suggests individual persistence within an arbitrary organization of formal circumstance.

The multivalent ambiguities of Mora’s studio operations are striking because the aspirational quality of nineteenth-century US photography are conventionally discussed in terms of fixed results and shared goals of social elevation. Andrea Volpe writes that cartes-de-visite contributed to the formation of middle-class identity by establishing the characteristics of a respectable type that could be “made real” through the visible proof of photographic portraiture.30 Trachtenberg similarly described the antebellum photographic studio as a “theater of desire” where the average American viewer might encounter portraits of presidents, generals, and other illustrious individuals and “make oneself over” in their resemblance.31 Yet these formulations imply that class elevation was a universal goal that was shared by and equally accessible to all American observers. In fact, of course, the social roles most photographic portraits presented were rigidly cast along racial and gender types that foreclosed the possibility of genuine belonging to many. By defying such singular sense of purpose, Mora’s photographs, operating in the unfixed atmosphere of the migrant surround, point to an adjacent emerging desire in the late nineteenth century to use photography as a means for departing from standardized scripts. Rather than adhering to conventional models of belonging, they suggest what Bhabha might call a “desire of hybridity,” in the strategic adoption of a discursive transparency that refuses the usual rules of recognition.32 While Mora’s subjects varied widely in terms of class, ethnicity, and social privilege, many appear to have been drawn to his portrait studio to craft public images that were removed from ordinary social order and departed from the text of any predetermined script. Like Ophelia, suspended for a moment on a river’s surface, or Mora’s bare operating room that could be rapidly redefined, these photographic visions encompassed a sense of indefinable in-betweenness, making them pictures of people only temporarily transformed and their photographs the artifacts of a process that did not necessarily represent their past or future form.

Re-reading the products of Mora’s studio within this context illuminates a framework for understanding the unreality of his richly constructed photographs as visual intermediary for the social and geographic mobility that shaped cultural experience for millions of Americans during this time period. Furthermore, it helps to situate Mora’s studio stagecraft within a larger global discourse that reaches beyond the United States, connecting it to a creative network of photographers working elsewhere in the Americas during the nineteenth century, such as Benjamín de la Calle, Martín Chambi, Antíoco Cruces, and Luis Campa, as well as later African portraitists such as Malick Sadibé and Seydou Keïta. For all of these photographers, the studio was an ad hoc performance space that could be mobilized and continually remade from textiles, artwork, and consumer goods in order to do the important cultural work of reimagining convention during disparate historic moments of cultural and national metamorphosis. The resonance of this portrait practice across time and national boundaries suggests the formal operation of the migrant surround as an answer to the myriad complications of representing identity in the context of radical change. Scholars such as Christopher Pinney and Jennifer Bajorek have written that it was precisely this “lack of fixity” in postcolonial photographic studios that allowed artists and subjects to refuse the entrenched hierarchies of colonial representational regimes.33 Pinney writes that photography offered an escape from the oppressive depths of prescribed type “by siting its referents in a more mobile location on the surface.”34

Late nineteenth-century studio practice in the United States similarly mobilized the framework of a migrant surround to oscillate between national identities and cultural systems of belonging. Occupying neither the untethered freedom of the surface nor the predetermined identities of its depth, the migrant surround suspended individual representation in a generative space between fiction and reality. It was a site for representing crucial transitions that were otherwise invisible by formulating an image not fully accounted for in any official text or set of national descriptors. In this way, more than documenting a moment in social history or the birth of US consumer culture, the photographic work of Mora and his contemporaries visualized the fluid hybridity of national identity during a time when more than twelve million new arrivals to the United States were reinventing and revitalizing what it meant to be American.

Envisioning “American” Character

Mora’s investment in photographic fantasy does not mean that the real-world concerns of the Cuban émigré community in New York City are absent from the imaginative spaces of his portrait practice. These weighty political and personal interests are instead more easily legible in the context and circulation of his seemingly lighthearted work than they are through direct reading of its subject matter. Among the first independent projects Mora completed after leaving Sarony’s studio was a Centennial Album containing a series of portraits depicting “the most prominent young ladies of New York fashionable society.” It was sold at a well-publicized raffle for the benefit of the Ladies’ Centennial Union as a fundraising gambit to support the women’s pavilion at the upcoming fair in Philadelphia. The album itself was a sumptuous object. Valued at $3,000, its covers were inlaid with sterling silver by Tiffany & Co. and filled with thick, gold-trimmed pages upon each of which was mounted a portrait by Mora.35 The material richness of this presentation lent value and prestige to the photographs and elevated their commercial sale above the level of ordinary cabinet card hawking. Yet beneath these glittering surfaces was more serious political purpose.

The Centennial Exhibition ostensibly celebrated the hundredth anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence, but its underlying stakes were considerably higher. Coinciding with the collapse of Reconstruction, and just a decade following the Civil War, it was perceived by many as an opportunity to heal the cultural rift between North and South through a new chapter in American nation-building—not by reckoning directly with recent events, but by mining the nobler origins of the country to fashion a new model of national character. As Kimberly Orcutt argues, the exhibition marked a self-conscious pivot point in US history, “a break between past and future,” when nineteenth-century Americans sought reassurance “that a reunified nation could move confidently into a larger, more complicated modern world.”36 As such it prompted an urgent call to look inward as well as out—to identify a collective public image from amid cosmopolitan influences, and determine how this vision measured up to national characters from around the world.

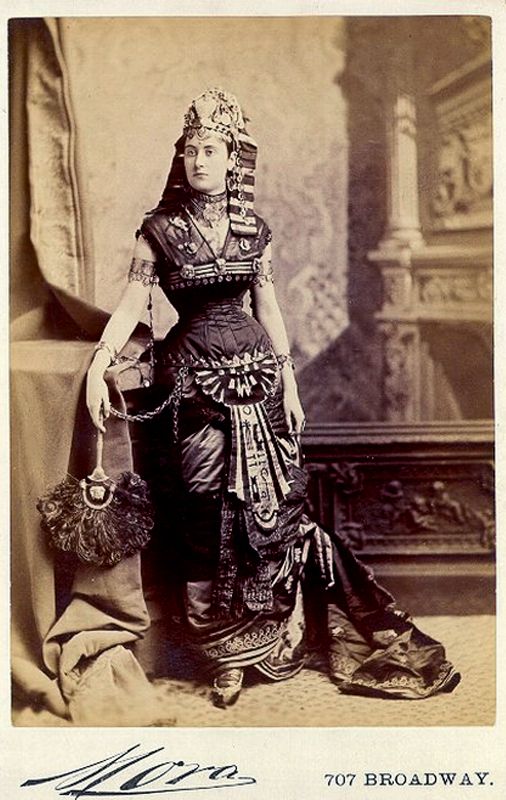

The Ladies’ Union, working in partnership with Mora, made this enterprise the explicit focus of their Centennial Album. Each of the white, upper-class women photographed was costumed to represent “one of the sixteen nations of the world,” which, according to a list Mora provided to the Photographic Times, were Egypt, Holland, England, Cuba, Ireland, Russia, Germany, Turkey, India, Asia, Lapland, China, France, Greece, and Spain—with the figure of Columbia included as an allegorical representation of the Americas.37 No explanation was given either for this limited number or the criteria used in their selection. Yet based on surviving photographs, it appears to have been in part due to the appeal of certain costumes and their photographic possibilities. Mrs. F. C. Barlow, who was dressed as a Laplander, posed beside a taxidermied polar bear. Minnie Stevens, daughter of the wealthy hotelier Paran Stevens, represented Egypt in a stunning gold headdress and tightly cinched corset that evoked the mythic allure of Cleopatra (fig. 5). Stevens’s choice of costume certainly was not motivated by any personal connection to the country, but more likely that she already owned the headdress, which she had worn to great public acclaim at a costume ball hosted at Delmonico’s restaurant four years earlier.38

This type of ethnic masquerade was a regular feature of nineteenth-century costume balls, which were a popular pastime for New York’s social elite, especially during the Gilded Age. Although costumes ranged from witches to fairy-tale characters to bumblebees, many wealthy participants chose to take on the guise of cultural, historical, or economic Others. Popular choices included French, Dutch, or English peasants; monarchs, such as Marie Antoinette and Mary Queen of Scots; or aristocratic courtiers inspired by Italian Renaissance portraiture.39 Considering the ascendency of this form of entertainment against a growing wave of global migration to the United States, the public act of ethnic masquerade took on an air of cultural gatekeeping, as wealthy classes of already-established Americans assumed the privilege of appropriating the national dress of more recent arrivals.

It is significant in this regard that none of the women pictured in the Centennial Album represented the United States specifically. At the later Vanderbilt costume ball of 1883, several women dressed as “Colonial Dames,” in lace caps and aprons inspired by conventional dress in the New England colonies, but a decade earlier this Anglo-Protestant caricature had not yet been adopted as an emblematic embodiment of US identity. Instead, in the Centennial Album, the allegorical figure of Columbia—represented as a Greek goddess cloaked in stars and stripes with a Phrygian cap of freedom—stood for a more vaguely defined notion of the New World. In this sense, the seemingly playful act of transnational pageantry participated in a weightier project of defining US national identity. It stood to reason, after all, that if Italian, Irish, or German identity were costumes that could be donned on special occasions, “Americanness” was the normative state that existed beneath—an unmarked category of universal identity that underlay the trappings of a theatrical extravagance. The Centennial Album also tacitly asserted whiteness as a condition of American identity by enacting ethnic otherness only within narrowly conceived, Eurocentric limits. It pointedly avoided racialized Native American or African American types that might have evoked the racist histories of settler colonialism and slavery, or highlighted the country’s foundational multiculturalism. These erasures seem particularly significant in the same year that the US government declared war on the Lakota people in the Black Hills and officially abandoned the full enfranchisement of millions of Black Americans along with the project of Reconstruction. Instead, in the Centennial Album’s roster of sixteen nations, Stevens’s portrayal of Egypt was the only representation from the African continent; Indigenous people were invisible; and while China, India, and Turkey each had individual representation, Mrs. R. Hunt was also cast more broadly as “Asia” in an outsized role that seemed to offer a tiny nod to the vast majority of world nations and people the album purposefully excluded.

These peculiar politics of representation and omission make it particularly significant that Cuba was prominently included among the sixteen nations in Mora’s Centennial Album. It appeared fourth on the photographer’s list, just after Holland and England, which were the most favored points of family origin for the members of Knickerbocker society, and well before Spain, which he ranked last. Representing Cuba as well as Spain within such a limited selection of nations subtly naturalized the idea of Cuban independence—as did the embodied distinction between Cuba and the more generalized allegory of Columbia. Moreover, the young woman chosen to portray the island nation was Leonor de Aldama, the youngest daughter of Miguel de Aldama, who was a leader of the US-based Cuban resistance movement to which Mora’s father also belonged.40 Pérez writes that the mass exodus of Cubans to New York during the Ten Years’ War of 1868 to 1878 heightened the city’s role as the most important setting for émigré separatist activism. “With a war raging in Cuba, that activism took on a greater urgency,” as did the public visibility and social acceptance of members of the diasporic community.41 As external support for the rebels—both financial and political—became a critical factor in the struggle for independence from Spain, “the volume and intensity of Cuban émigré activities in New York were turned up substantially and became more visible elements in the city’s landscape.”42

In this sense, Mora’s Centennial Album lent Cuba visibility among the roster of nations and placed Miss Aldama among the “the most prominent young ladies of New York fashionable society,” representing a political gambit cloaked in the frivolity of social theater—one that reveals the messy realities of nineteenth-century national identity that are easily overlooked within “elaborate style” portraiture. It also demonstrates the potentially meaningful reoccupation that might be performed within the migrant surround. Unlike most of the other young women who had no personal relation either to their national costumes or the landscapes constructed by Mora as portrait backgrounds, the stakes for Aldama were considerably different. Her position, and that of other Cubans displaced during the Ten Years’ War, was summed up in a passenger log that recorded her arrival in New York in January 1873. Traveling from Liverpool in the company of her sister- and brother-in-law, she listed the country to which she belonged as “An exile of Cuba” and her ultimate destination as “Exile”—suggesting this sense of national displacement would eclipse all other possible identities even once her ship had landed.43 For her, then, posing as Cuba within the constructed surround of Mora’s studio was an opportunity to reinhabit her home country from afar—not in reality, but through an imaginative act of photographic transportation that was in that moment the only available alternative.

The Mora Claim

Mora’s career as a photographer was an unintended outcome of his exile from Cuba, a diversion from his original aspiration of being a painter and what might perhaps have been a more conventional pathway to artistic success. The energy he invested in his extravagant studio compositions and backgrounds suggest that he regularly drew upon his interrupted early training despite the change in professional direction. And, under certain circumstances, it appears that the playful shape shifting of his portrait process facilitated an imaginative realization of this lost possibility. An 1883 photograph he made of Consuelo Yznaga Montagu, Viscountess Mandeville (and later the Duchess of Manchester) demonstrates such a photographic encounter (fig. 6). Consuelo Yznaga was a New York–born socialite of Cuban descent. Her marriage in 1876 to George Mandeville, a titled British peer, made her an exemplar of the ascendency of the Cuban diaspora in New York. Mora’s photograph was taken on the occasion of the 1883 costume ball hosted by Consuelo’s childhood best friend, Alva Vanderbilt. Both women dressed as figures from paintings for the event—Vanderbilt as a Venetian princess from a work by Alexandre Cabanel, La Patricienne de Venise (1881; private collection), and Consuelo as Marie-Claire de Croÿ from a portrait by Anthony van Dyck, Marie-Claire de Croÿ with Her Son Philippe-Eugène (1634; Legion of Honor, Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco). Mora photographed the two women along with many other guests of the event, but the number of varied portraits of Consuelo suggests she may have spent additional time with the photographer in a more extended portrait session. Attempting to capture the spirit of the source of inspiration for her costume, one of Mora’s photographs mimics the flowing drapery in Van Dyck’s original composition and employed composite printing to apply a border in the style of an ornate gesso frame. Above the script signature that appeared on the cardboard mount of all of his cabinet cards, Mora scratched a new artist’s name into the emulsion in the lower right corner of the image: “A: Van Dick: F.” By the transitive properties of the portrait process, the act of transforming Montagu into Marie-Claire de Croÿ positioned him as a modern-day Van Dyck—a respected artist of secure reputation with a place in the societal court—with the “F” following the name representing an important update: fotógrafo rather than painter, a choice that underscored Mora’s native tongue as well as his adopted medium.

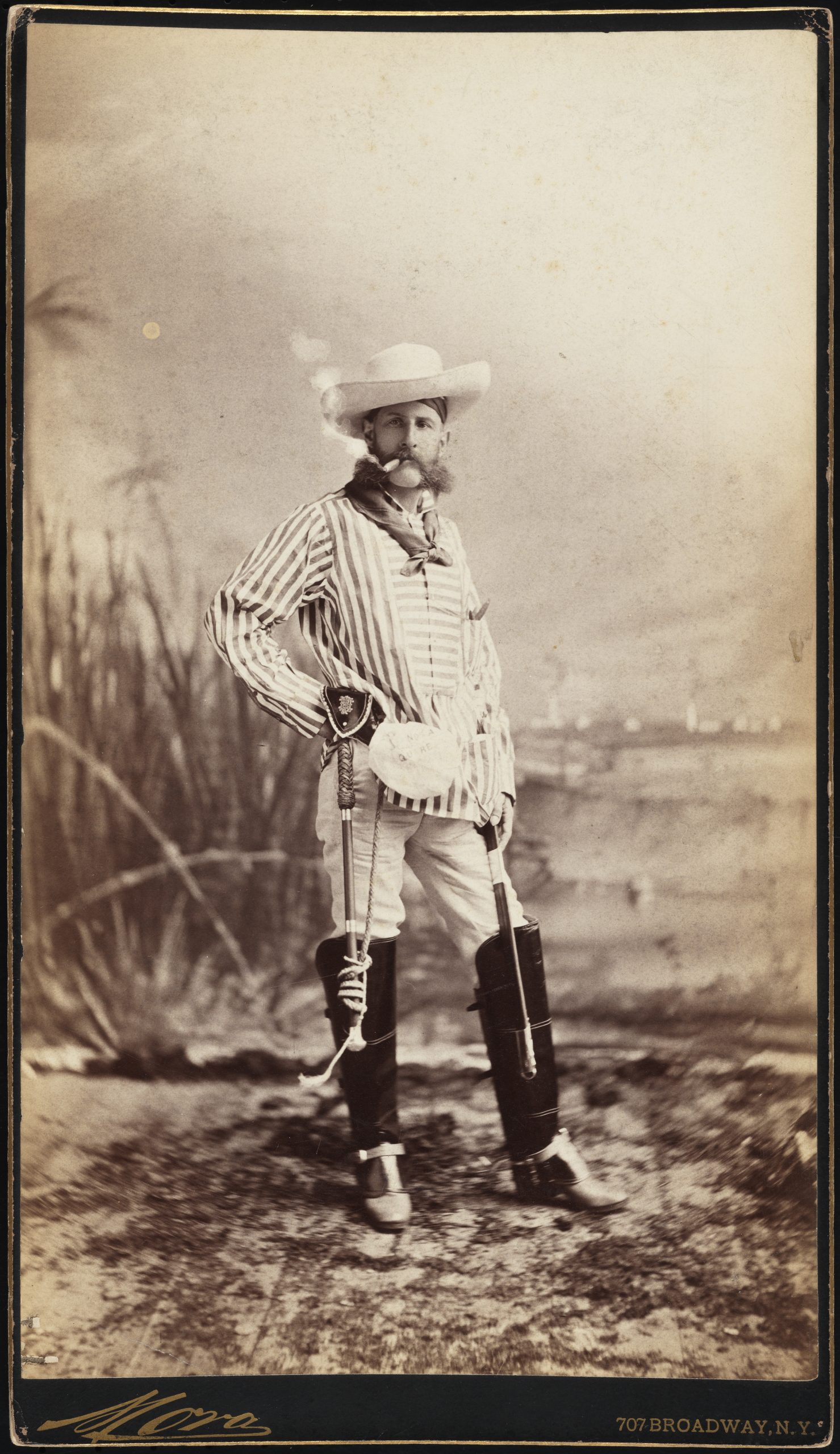

While photographing Consuelo may have enacted a fantasy of belonging, there were other persistent reminders of Mora’s outsider status in the elite circles of Manhattan society. At the same 1883 event, John Halsey Haight, wealthy scion of a family of insurance agents, appeared in a costume described as a “South American Rancher,” smoking a short cigar while wearing a pastiche of Caribbean and Latin American clothing items, including a wide-brimmed hat and a guayabera, and carrying a rebenque, or rawhide whip (fig. 7).44 Mora’s photograph appears to place Halsey Haight as the owner of a sugar plantation. Palm trees and crossed stalks of cane rise in the left, while a cluster of small white buildings and short smokestacks is visible in the painted distance of the landscape on the right. Instead of relishing what might be an opportunity to approximate his personal origins on his family’s lost plantation in Cuba, Mora’s rendition of the scene is uncharacteristically spare. The canvas of the backdrop sags visibly along its lower edge, and rough wood beams show clearly through scattered soil and pebbles that only partially cover the studio floor. It is possible that the crush of portrait business from the Vanderbilt ball simply made it difficult to conceive a fully immersive scene for every client, but the incomplete rendering of Halsey Haight’s photographic environment—the persuasive failure of the portrait surround that transported so many of Mora’s other subjects—appears on some level to bar the wealthy New Yorker from imaginatively entering a world where he did not belong, but dared nonetheless to caricature as a source of amusement.

If Mora benefitted early in his career from his class position as a white criollo of Spanish descent, rather than a racialized Cuban of Indigenous or African descent, which allowed him some ability to blend with New York City’s elite society, the effort of this engagement seems to have worn on him over time. By 1887, his portrait studio had begun to fail, perhaps in part, as David Shields has speculated, due to the escalating pressure his family’s political situation placed upon his business.45 In 1888, he closed his studio permanently, ceasing all professional work as a photographer and selling the rights to his negatives to the dealer Charles L. Ritzman. The end of this once-prominent society photographer’s career arrived with little fanfare or acknowledgment. The New-York Tribune only stated in a two-line report that Mora attributed his failure in business to “too much theatrical photographing.”46 In the absence of additional information, it is impossible to know what he meant by the statement. It could suggest that he felt regret over not diversifying his business into other areas of production, or relying too much on the whims of popular taste. The peculiar phrasing, however, makes it possible to speculate that it was his theatrical approach to photography itself that also proved a strain. The immense personal and emotional effort required to generate make-believe worlds in his studio, to negotiate the social encounters of the portrait process, or to repeatedly manufacture a sense of place for his sitters and himself—stepping back and forth between realities—may gradually have taken a toll.

Whatever the case may be, after ending his professional life as a photographer, Mora’s time and mental energy appears to have been consumed by an intensive battle to win compensation for his family for the land seized by the Spanish government in 1868. Since the eldest of his uncles had been a US citizen at the time, the family successfully lobbied the State Department in 1880 to aid in recovering a financial settlement for their seized property, requesting a sum of two million dollars.47 At the outset, the Mora family apparently hoped their bid for reparation would support the cause of Cuban independence by depleting the finances of the Spanish crown and tarnishing its reputation in the United States. The international legal battle that ensued, which was popularly known as “The Mora Claim,” stretched on for decades, ultimately becoming inculcated in the US government’s imperial ambitions in the Caribbean. When a sum was finally agreed to in 1895, Spain delayed payment, and President Grover Cleveland interceded—applying pressure on the Spanish government by dispatching Navy ships just outside the port of Havana until rumors circulated through Madrid that the United States meant to hold the city hostage until the claim was paid.48 This intervention was less a matter of protecting the Moras’ interests, however, than of advancing those of the United States. In subsequent years, even after the matter was resolved, newspapers characterized the Mora Claim as demonstration of the power of the US government to vanquish a foreign adversary. In July 1898, at the midpoint of the Spanish-American War, Horatio S. Rubens, a supporter of US intervention on the island, described the Mora Claim as the first step leading to the conflict. “Nothing has ever arisen between America and Spain which Spain has not conceded. . . . To begin with, Spain insisted it would not pay the Mora claim. When the United States insisted, she did pay it just the same.”49 In the end, the Moras’ suit was not interpreted as justice secured for US citizens and their Cuban allies, or a victory for two sibling nations in the Americas, but instead served as a diplomatic cudgel used by the United States to assert dominance in the region.

Once his family’s legal claim was settled, Mora dropped completely from the public eye until shortly before his death in 1926. The Washington Post reported that the long-lost photographer of the Gilded Age elite, now an eccentric recluse, had been discovered living in the Hotel Breslin in Manhattan. Mora had actually moved in decades before and escaped recognition by referring to himself only as “Old Joe,” rather than revealing his true name. He apparently spent his days in the hotel restaurant, appealing to guests to buy him cake or pie, despite having the majority of his share of his family’s land settlement—more than $200,000—remaining in his bank account. When hotel staff entered his room after his death, they discovered that his bathtub was filled entirely with old cabinet cards and his walls papered over with theater posters and playbills from the 1870s and 1880s.50 Although he had abandoned his career as a photographer three decades earlier, the portraits he created of fictional characters in fantastical environments clearly still held meaning as a reminder of another time and place, an absorbing alternate reality he had once inhabited.

The question of how to re-read these photographs as cultural texts, or to place them within a canon of US photography, prompts deeper consideration of how national realities related to citizenship and immigration policies have shaped individual ability to claim American identity—both in the past and present. It also provides an important reminder that “America,” in its greatest sense, is a generous and embracing term, expansive enough to include the interconnected populations of an entire hemisphere and describe the complex lived realities of their diverse cultural experiences; it spans entangled transnational histories as well, as is evidenced by the evolving relations of Cuba and the US during the nineteenth, twentieth, and twenty-first centuries. Part of the reason the work of Gilded Age photographers appears disengaged from reality was the transitional nature of the moment in which they worked—both in terms of national history and the technological development of their medium. The mutable spatial construct of the migrant surround visualized the cultural fluency of large transnational communities who made the United States their home in the late nineteenth century through a mode of portraiture that declined to fix the identity of either image maker or subject within the easy legibility of conventional symbols. Newspaper reports of the 1888 New York City funeral of Cuban patriot Miguel de Aldama describe an analogous kind of image. Although Aldama died in Havana, he had requested that his body be buried in the United States—the country that was his home for more than a decade as he fought for the cause of Cuban independence. The uncertainties of international transit ultimately necessitated somewhat ad hoc funeral arrangements, with Aldama lying in state for a full day in the corner of Pier 3 on the Hudson River before his planned interment at Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn. When his casket arrived in New York, a well-intentioned longshoreman, recognizing Aldama’s importance but misunderstanding Cuba’s contested political situation, draped the coffin with the Spanish flag. This was quickly removed once Aldama’s family and friends arrived and replaced with the US flag. Yet this marker did not seem wholly appropriate either, so the stars and stripes were in turn gradually covered by floral tributes as throngs of individuals from the Cuban diasporic community in New York visited to pay their final respects.51 The incident recalls the insufficiency of fixed symbols and static ideals in representing the ambiguities of identity, belonging, community, and kinship—the absences and erasures that often speak more eloquently to lived history than its material traces. Bending the borders of reality in his studio, Mora’s photographic experiments in the migrant surround grasped at this fluid sense of belonging, sliding subjects from one role to another as easily as changing costumes, or flags atop a casket. In the absence of a more effective visual language for expressing the complications of national identity in the Americas during the late nineteenth century, heaping flowery theatrical gesture upon these starker realities would have to do.

Acknowledgments

I wish to thank my colleagues Mariola V. Alvarez and James Merle Thomas at Temple University’s Tyler School of Art and Architecture for invaluable feedback on early drafts of this article, and extend special gratitude to Monica Bravo and Emily Voelker for meaningful guidance in its final development. Thanks as well to Kaelin Jewell, Emily Schollenberger, and Lily F. Scott for their intrepid research assistance; Dale Stinchcomb at the Harvard Theatre Collection for aiding with images; and Shannon Piercy Alvarez for supporting this project from the start. I also gratefully acknowledge E. Carmen Ramos for enthusiastically encouraging this inquiry in an earlier form, and my mentor Sarah Burns whose boundless curiosity and encyclopedic memory banks helped guide me toward Mora’s costume ball photographs in the first place.

Cite this article: Erin Pauwels, “José María Mora and the Migrant Surround in American Portrait Photography,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 6, no. 2 (Fall 2020), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.10613.

Notes

- Examples of texts that make this connection are Robert Taft, Photography and the American Scene (1938; reprint, New York: Dover, 1964); Floyd and Marion Rinhart, American Daguerreian Art (New York: Crown Publishers, 1967); and Beaumont Newhall, History of Photography from 1839 to the Present Day (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1949). Mia Fineman has argued more broadly that the tendency to construct narratives of photographic history from a modernist point of view around progress toward enhanced realism resulted in the counter formation of a “secret history of photography,” which contains a roster of rarely discussed outliers. See Fineman, Faking It: Manipulated Photography before Photoshop (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2012), 6. ↵

- Taft, Photography and the American Scene, vii. ↵

- Alan Trachtenberg, Reading American Photographs: Images as History Mathew Brady to Walker Evans (New York: Hill and Wang, 1989), xvii. ↵

- Trachtenberg, Reading American Photographs, xiv. ↵

- Trachtenberg, Reading American Photographs, xvi. ↵

- Trachtenberg, Reading American Photographs, 288. ↵

- For critical discussion of the role of cabinet cards in nineteenth-century visual culture, see John Rohrbach, Erin Pauwels, Britt Salvesen, and Francesca Valverde, Acting Out: Cabinet Cards and the Making of Modern Photography (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2020). ↵

- “The New Size,” Philadelphia Photographer 3, no. 34 (October 1866): 311–13. ↵

- William B. Becker, “Cabinet Cards,” in Encyclopedia of Nineteenth Century Photography, vol. 1, A–I, ed. John Hannavy (New York: Routledge, 2008), 233–34; and John Plunkett, “Carte-de-Visite,” in Hannavy, Encyclopedia of Nineteenth Century Photography, 1:276–77. ↵

- For more on the visual mechanics of photographic backdrops, see Arjun Appadurai, “The Colonial Backdrop,” Afterimage 24, no. 5 (1997): 4–7; Kate Flint, “Surround Background, and the Overlooked,” Victorian Studies 57, no. 3 (Spring 2015): 449–61; and Christopher Pinney, Camera Indica (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998). ↵

- See Taft, “Kurtz, Sarony, and Mora,” in Photography and the American Scene, 336–60. ↵

- Taft, “Kurtz, Sarony, and Mora,” 334–35. ↵

- For example, see: T. J. Jackson Lears, No Place for Grace: Antimodernism and the Transformation of American Culture, 1880–1920 (Chicago: University of Chicago, 1981) and Miles Orvell, The Real Thing: Imitation and Authenticity in American Culture, 1880–1940 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1989). ↵

- See William Shakespeare, Hamlet, Prince of Denmark, 4.7.175–76, 181–83. References are to act, scene, and line, in The Riverside Shakespeare, 2nd ed. (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1997), 1225. ↵

- See Neil Harris, “The Operational Aesthetic,” in Humbug: The Art of P. T. Barnum (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1973), 59–89. Jordan Bear argues further that similarly puzzling visual effects were instrumental in advancing acceptance of photography as art. See Bear, Disillusioned: Victorian Photography and the Discerning Subject (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2015). ↵

- Lawrence W. Levine has established that Shakespeare was a many-splendored thing in the nineteenth-century US theater, providing inspiration for an array of high- and lowbrow stage iterations. Branscombe’s turn as Ophelia was the latter type of production. See Levine, “William Shakespeare and the American People: A Study in Cultural Transformation,” American Historical Review 89, no. 1 (February 1984), 34–66. For a more complete accounting of Branscombe’s career onstage and in photography, see Erin Pauwels, “‘Let Me Take Your Head’: Photographic Portraiture and the Gilded Age Celebrity Image,” in Beyond the Face: New Perspectives on Portraiture—The Smithsonian Institution National Portrait Gallery 50th Anniversary Volume, ed. Wendy Wick Reaves (London: D. Giles, 2018); and David S. Shields, “Maud Branscombe: Biography,” Broadway Photographs, accessed August 2020, https://www.broadway.cas.sc.edu/content/maude-branscombe. ↵

- T. J. Demos, The Migrant Image: The Art and Politics of Documentary during Global Crisis. (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2013), 3. In choosing the evocative term “surround,” I am informed also by James Elkins’s construct of the photographic surround, and Kate Flint’s well-founded interrogation of his notion within the context of nineteenth-century visual culture. See Elkins, What Photography Is (New York: Routledge, 2011); and Flint, “Surround, Background, and the Overlooked,” 449-61. There is also resonance between nineteenth-century media and the twentieth-century immersive phenomena explored in Fred Turner, The Democratic Surround: Multimedia & American Liberalism from World War II to the Psychedelic Sixties (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013). ↵

- Homi Bhabha, The Location of Culture (London: Routledge, 1995), 126–27; and Edward Said, “Intellectual Exile: Expatriates and Marginals,” Grand Street 47 (Autumn 1993): 121. ↵

- Miguel de Aldama, José María Mora, Hilario Cesneros, Francesco Fesser, and J. M. Mestre, “Manifesto of the Cuban Junta,” New York Herald, January 4, 1870, 1. ↵

- “Prominent Cuban Leaders Sentenced to Death,” Baltimore Sun, November 23, 1870, 1. Neither Mora’s father nor his uncle ever faced this sentence. His father moved to Brazil in the 1880s and died there in 1892, while his uncles lived in New York for the rest of their lives. ↵

- Lisandro Pérez notes that the Moras made significant investments in Manhattan real estate and rented a large number of properties on Twelfth and Thirteenth Streets between Second and Third Avenues to their compatriots, making this area a stronghold for the Cuban diaspora within the city. See Pérez, Sugar, Cigars, and Revolution: The Making of Cuban New York (New York: New York University Press, 2018), 240–41. ↵

- Pérez, Sugar, Cigars, and Revolution, 148. ↵

- Index to Petitions for Naturalization filed in New York City, 1792–1989 (online database). Provo, UT: Ancestry.com, 2007. ↵

- E. K. Hough, “Mora,” Philadelphia Photographer (July 1878), 248–49, 248. ↵

- Professor Greene, “Can Photography Make Pictures?” Photographic News 21 (May 25, 1877): 244. ↵

- As in the large urban studios of his contemporaries, Mora would have relied on a staff of studio assistants to perform much of the hands-on labor of setting up props and developing and printing photographs. For the operations of nineteenth-century American photographic studios, see Barbara McCandless, “The Portrait Studio and the Celebrity: Promoting the Art,” in Photography in Nineteenth-Century America, ed. Martha Sandweiss (Fort Worth, TX: Amon Carter Museum of American Art, 1991), 48–75; and Pauwels, “The Art of Not Posing: Napoleon Sarony & Popularization of Pictorial Photography,” in Acting Out, 20–38. ↵

- Hough, “Mora,” 249. ↵

- “Matters of the Month: Mr. Costa,” Photographic Times 9, no. 101 (November 1879): 259. ↵

- A vivandière or cantonière is a French name for women attached to military settlements as canteen keepers, but the question of why a respectable society matron dressed as if performing this function in service of the devil is more difficult to answer. In their catalogue entry for a similar portrait by Mora (41.132.55), The Museum of the City of New York notes that Pelham Bend may have worn the costume for the Opera Bouffe Quadrille at the Vanderbilt Ball. This possibility, along with the Mephistophelian plumes on her headdress, suggests her choice could have been inspired by the role of Totchen, a vivandière character who appeared in the Meyer Lutz musical burlesque version of Faust on London’s West End in the 1880s. Nonetheless, period sources suggest that her costume was neither familiar nor wholly uncontroversial even among original observers. Reflecting on the Vanderbilt Ball, George Augustus Sala wrote, “There was a married lady who wore the costume of a ‘Vivandière du Diable’—whatever that may be.” See Sala, Echoes of the Year 1883 (London: Remington, 1884), 154. ↵

- Andrea Volpe, “Cartes de Visite and the Culture of Class Formation,” in Middling Sorts: Explorations in the History of the American Middle Class, ed. Burton J. Bledstein and Robert D. Johnston (New York: Routledge, 2001), 157–69. ↵

- Trachtenberg, Reading American Photographs, 40. ↵

- Bhabha, The Location of Culture, 106–20. ↵

- Jennifer Bajorek, Unfixed: Photography and the Decolonial Imagination in West Africa. (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2020), 9; and Christopher Pinney, “Notes from the Surface of the Image: Photography, Postcolonialism, and Vernacular Modernism,” in Photography’s Other Histories, ed. Christopher Pinney and Nicolas Peterson (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2003), 202–20. ↵

- Pinney, “Notes from the Surface of the Image,” 203. ↵

- “Mora’s Centennial Album,” Photographic Times 6, no. 67 (July 1876): 149–50. ↵

- Kimberly Orcutt, Posterity and Power: American Art at Philadelphia’s Centennial Exhibition (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2017), 10. ↵

- See “Mora’s Centennial Album,” 149–50. ↵

- Mora’s elder brother, José Manuel Mora, was a close friend of Charles Delmonico, the owner of the restaurant, and may have been responsible for making the introduction that earned this photographic job. As an aside, both Mora brothers were frequently described in period newspapers as J. M. Mora, making it difficult to distinguish between the two of them. Manuel, however, seems to have been the more public figure. A wealthy financier and supporter of the theater, Manuel for years listed Delmonico’s as his primary address. Most references to that effect, including a description of J. M. Mora as a “first-nighter” at Broadway theaters, which is reproduced in Taft and elsewhere in reference to the photographer, actually describe Manuel rather than José María Mora. ↵

- My speculation is that the prevalence of these types of costumes represents the class striving of Euro-American New Yorkers, eager to conflate their social positions in the United States with a longer history of European aristocracy by mimicking the faux rustic amusements at Versailles or inserting themselves imaginatively in royal positions. For more on Gilded Age costume balls, see Wayne Craven, Gilded Mansions and High Society (New York: W. W. Norton, 2009), 123–29; and Eric Homberger, Mrs. Astor’s New York: Money and Social Power in a Gilded Age (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002). ↵

- I remain on the hunt for a surviving example of this photograph. It may exist in the archives of the New-York Historical Society or the Museum of City of New York, between which the largest surviving collection of Mora’s costume ball photographs has been split. I have been prevented by the COVID-19 pandemic from visiting these archives in person while drafting this article. I look forward to the day when this will again be possible, and in the meantime welcome information about the photograph from readers. ↵

- Pérez, Sugar, Cigars, and Revolution, 214–16. ↵

- Pérez, Sugar, Cigars, and Revolution, 216. ↵

- Passenger Lists of Vessels Arriving at New York, New York, 1820–1897. Microfilm Publication M237, 675 rolls. NAI: 6256867, Records of the US Customs Service, Record Group 36, National Archives, Washington, DC. ↵

- Many of the costumes worn by wealthy guests photographed by Mora at the 1883 Vanderbilt Costume Ball are described and listed in an anonymous article written “As if by Frederick Townsend Martin,” entitled “Mrs. Vanderbilt’s Gracious Gesture to Society,” The Stage 14 (August 1937): 94–95. ↵

- Shields writes that Mora’s “distraction contributed materially” to the decline of his professional fortunes. See David S. Shields, “Jose Maria Mora,” Broadway Photographs, accessed May 2020, https://www.broadway.cas.sc.edu/content/jose-maria-mora. ↵

- “About the Stage and Its People,” New-York Tribune, December 12, 1888. ↵

- John Bassett Moore, History and Digest of the International Arbitrations to which the United States Has Been a Party . . . (Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office, 1898), 2397–98. ↵

- “Payment of the Mora Claim,” Washington Post, June 23, 1895, 1. ↵

- “Sees a Spanish Backdown,” Baltimore Sun, March 30, 1898, 1. ↵

- The publications relating the sad circumstances of his death got his name wrong, describing him as Maria Jose Mora. See “Maria Jose Mora Dead,” New York Times, October 19, 1926, 29; and “Aged Wealthy Recluse Lives on 15 Cents Daily,” Washington Post, June 13, 1926, M17. The 1925 New York State Census lists Mora living at the Hotel Breslin under the name Joseph rather than José. See State Population Census Schedules, 1925, Election District 26; Assembly District 10, New York, New York, 11, New York State Archives, Albany, New York. ↵

- “Miguel de Aldama’s Funeral,” New York Times, March 30, 1880, 8. ↵

About the Author(s): Erin Pauwels is Assistant Professor of Art History at the Tyler School of Art & Architecture, Temple University