Frank Speck in N’Daki Menan: Anthropological Photography in an Extractive Zone

A photograph from 1913 captures the crew of the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) longboat at dinner. A group of fifteen Indigenous men and children sit in an overgrown clearing in Temagami, a small community in northern Ontario that is on the traditional territory of the Teme-Augama Anishnabai (fig. 1). Two groups of standing men (in the center and far right) mimic the tree line behind them. In the front left corner, dense underbrush provides a compositional counterpoint to the neatly packed supplies anchoring the far right corner. Throughout the image, dappled light and textured foliage provide depth, guiding the eye through the group of men and framing them in the natural setting. The group portrait captures workers at rest. In the immediate foreground, a man faces away from the camera, although everyone else looks directly at it. In the center of the frame, a young boy peers out from behind the man in front of him, directing his gaze to the photographer. The boy holds a roll of Kodak film (fig. 2).

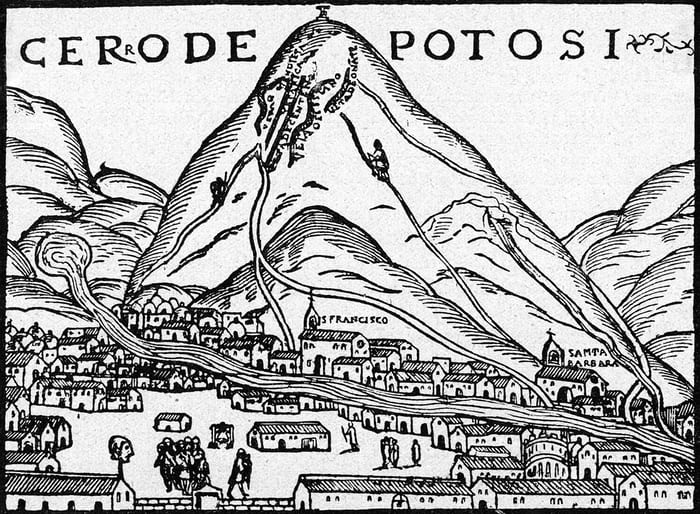

The inclusion of the roll of film introduces a confrontation to settler expectations of what it meant to be Indigenous in the early twentieth century. At that time, Temagami was a popular wilderness tourism destination for Americans, where Indigenous guides added perceived authenticity to this back-to-nature experience. The formal structure of the image emphasizes the incongruity between the old-growth Temagami forest, which had come to symbolize a primeval nature for tourist literature during this period, and the roll of Kodakfilm, an overt symbol of modernity. There were circulating narratives that cast Indigeneity as a disappearing way of life, such as the suggestion that “the bark canoe will soon be a method of travel known only through the pages of history.”1 The coexistence of a traditional form of labor (symbolized by the longboat, a narrow canoe used to carry cargo) and technological modernity (the camera/film) holds tradition and the contemporary in balance and asserts the possibility of being both Indigenous and thriving in the modern world (fig. 3).

While the photograph highlights the coexistence of tradition and adaption, it was taken in a period of considerable pressure on the Teme-Augama. In the decade before the photograph was taken, life in the region had been transformed by mining and logging that had limited Indigenous access to their own territory and disrupted traditional land-use patterns. Resource extraction created what cultural theorist Macarena Gómez-Barris describes as an “extractive zone,” a place whose constitutive logic was geared toward what could be taken out of the earth and transformed into value.2 The rise of large-scale extraction brought miners and timbermen to the region, as well as geologists working for the Geological Survey of Canada (GSC). The GSC also sent anthropologists, including the Philadelphia-based anthropologist Frank G. Speck (1881–1950), a professor at the University of Pennsylvania.

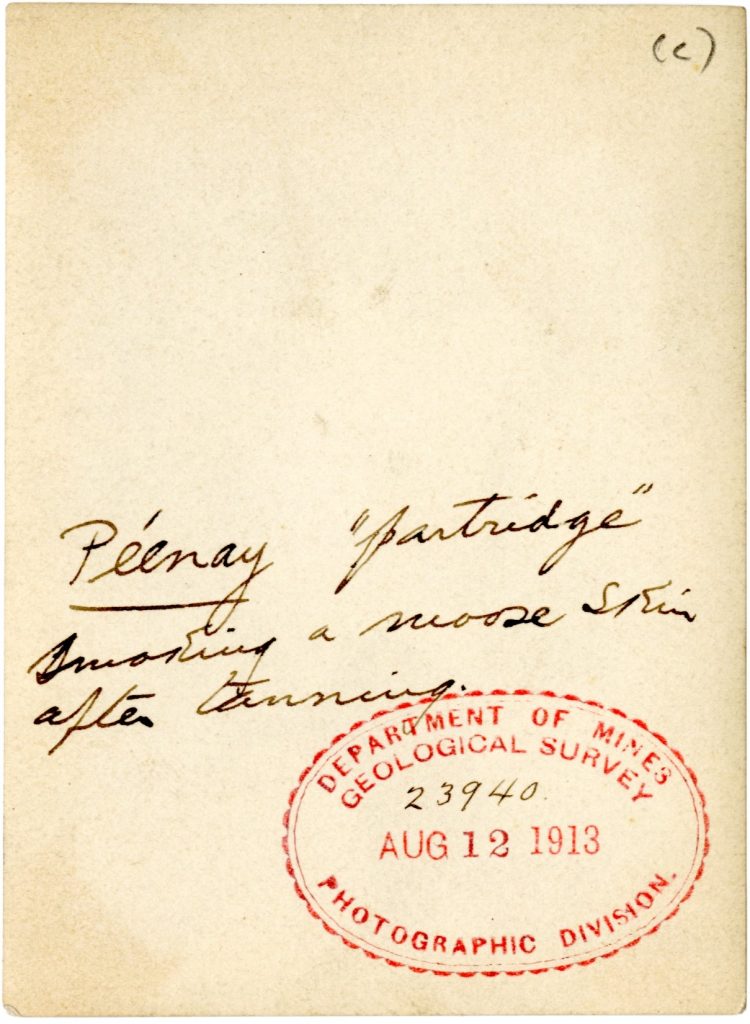

In 1913, Speck traveled to Bear Island, a small island on Lake Temagami, to study the experiences and folklore of the Teme-Augama under the auspices of the Anthropological Division of the GSC.3 The photograph of the HBC crew was likely taken by Speck.4 It is archived in the Frank G. Speck collection at the American Philosophical Society and was originally mounted in a photo album titled “Ojibwa Temagami Ont.,” which contained just fewer than one hundred photographs.5 The photographs were taken as the community advocated for a reserve to preserve their rights to territory. Chiefs William Berens and Aleck Paul asked Speck to advocate to the Canadian government for their territorial rights that were under pressure due to tourism and extraction (fig. 4).6

Extraction is both a material process and a worldview.7 Materially, it describes the physical processes of extracting raw natural materials from the earth. As a worldview, extraction views nature—and the people understood as being part of nature—as a resource to be expropriated. This way of seeing nature promotes economic growth as a priority, instead of sustainability. Once extracted, raw natural materials are transformed into commodities that are traded in global markets. Extraction is therefore the first step in an accumulative process through which materials are transformed into wealth. Some of these raw materials are transformed into the material foundations for making art. Photography can also be understood as an extractive process, where the photographer with institutional power extracts meaning, beauty, or pain from the subject. Extraction is the operative framework that I am exploring, both for mining and for the creation of photographs of Indigenous people for settler society.

In this article, I situate Speck’s archive of photographs within the economic and environmental transformations that occurred in this region in the first two decades of the twentieth century. This archive of photographs is situated in the complicated histories of anthropology, taxonomy projects sponsored by the state, and the promotion of extraction by the GSC. Extraction, however, is never an all-encompassing process that displaces all other forms of living and relating.8 This archive is a valuable record of how a community negotiated a moment of considerable change. I argue that Speck acted as a mediator between the government and the community, translating their experiences in a way that would be legible to anthropologists and a government that prioritized development. The photographs present a challenge to narratives of terra nullius (nobody’s land) by documenting the Teme-Augama’s ongoing presence and ties to land, even amid upheaval in traditional land-use patterns caused by extraction.9 I conclude by analyzing how these anthropological photographs were reactivated by the Teme-Augama decades later during a Supreme Court challenge over land rights.

The Geological Survey of Canada, Salvage Anthropology, and Extraction

The anthropological use of photography dates back to the emergence of the medium, forming what anthropologist Christopher Pinney describes as a “doubled history.”10 Throughout the Americas, scientists and the state used photography to accumulate a record of the conquest of Indigenous territories and people. While Canada’s Department of Indian Affairs (DIA) amassed a collection of more than eighty thousand photographs starting in 1880, many portraits that documented Indigenous people and their lives were taken and collected by the GSC, echoing a similar process undertaken in the United States.11 Topographical government survey projects adopted photography early on and comprehensively.12 These photographers often also photographed Indigenous people in North America, as the territory surveyed for potential fossil fuel or mineral extraction was frequently a site of contact between settlers and Indigenous nations.

The GSC was founded to develop Canada’s mineral knowledge and, by extension, mineral wealth. Yet within the GSC, the natural sciences were broadly defined, and specialized branches spanned a variety of outdoor sciences, including anthropology. Until the mid-twentieth century, Canadian anthropology programs were typically run and staffed by anthropologists trained in the United States, reflecting the lack of specialized training in the discipline within Canada. R. W. Brock, director of the GSC (1907–14), asked Franz Boas for a recommendation of an anthropologist to spearhead the Anthropology Division at the recently established Victoria Museum in Ottawa. Boas responded that there were no Canadians sufficiently trained in proper anthropological methods, and Brock would have to hire a US citizen. Edward Sapir, a student of Boas and a friend of Speck, was hired to run the department, housed in the Victoria Memorial Museum in Ottawa.13 Sapir supported Speck’s fieldwork in Temagami. This cross-border exchange of skilled labor highlights a hemispheric interconnectedness and dependency, as well as the international nature of anthropology and its forms of knowledge as a professionalizing field.

The mandate of the division was to carry out scientific research among all Indigenous people in Canada, in what would now be described as “salvage” anthropology. Salvage anthropology was rooted in the belief that Indigenous culture was corrupted by modernity and would eventually vanish; Boas was a leading voice in this field. In this framework, the anthropologist attempted to preserve Indigenous culture before it was lost.14 The relative isolation—and therefore, the authentic culture that had not been corrupted by modernity—of the Teme-Augama band was considered important to preserve, especially at a time when that culture was threatened as extraction brought settlers and industry to the region.

In the real-photo postcard of the boy holding Kodak film, the consequences of this extraction are not visible within the photographic frame; however, as an image-object, the photograph has a material connection to mining. As in many analog photographs, light-sensitive silver halides were used to produce the image. As art historian Robin Kelsey observes: “The emergence of silvery images in the darkrooms of photography has therefore always had a grim counterpart in the extraction of silver underground.”15 Furthermore, the discovery of silver in the nearby town of Cobalt in 1903 provided a source of cheap silver for rapidly expanding photographic industries as well as disrupting the Teme-Augama’s access to territory. As a physical object, the photograph highlights linkages between extraction, colonialism, environmental damage, and photography.

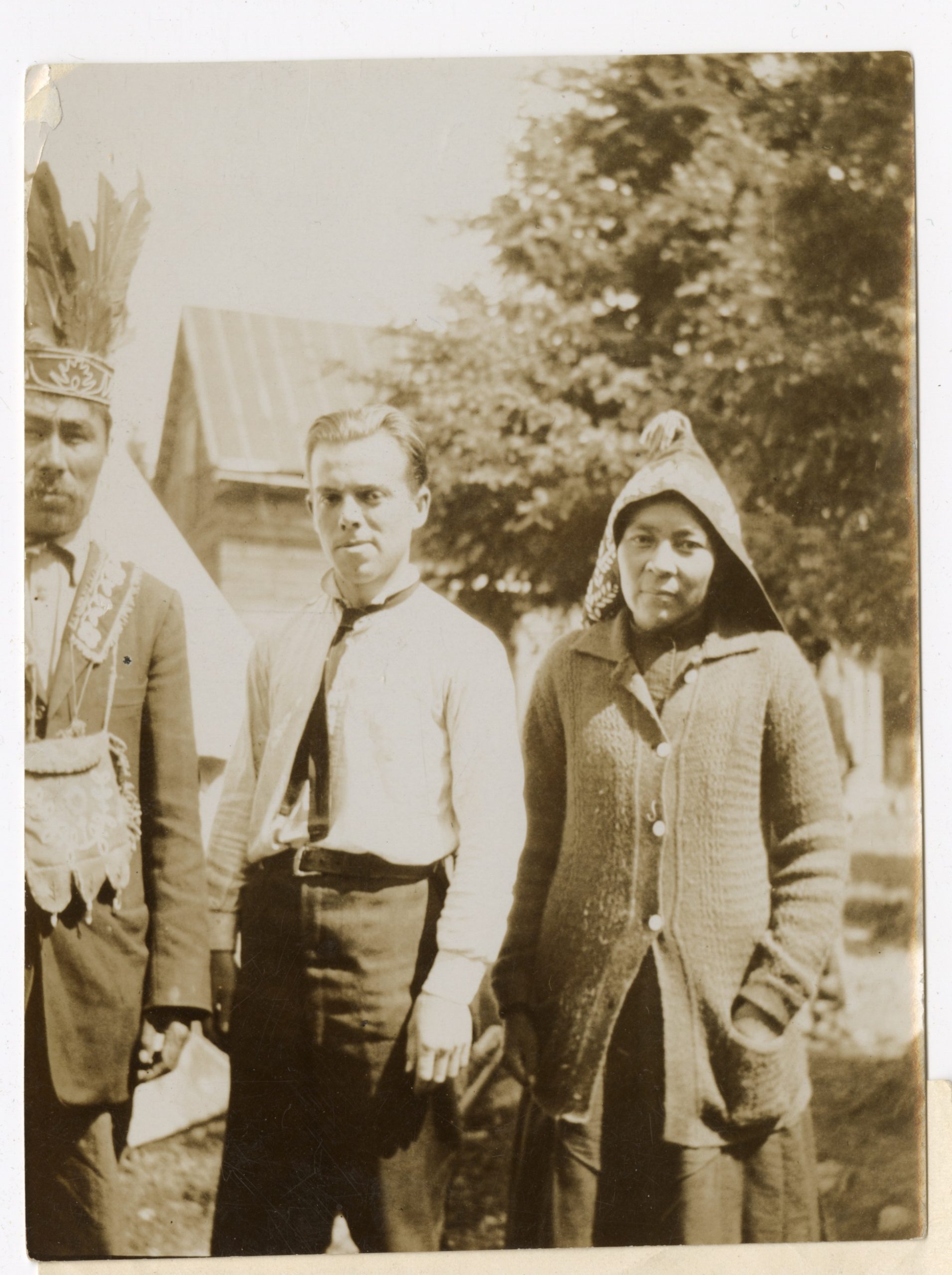

Photography’s material foundations in silver and silver mining draw attention to the hemispheric links between mining, capital investment, and photography. The extraction of metals and minerals under the oversight of colonial empires transformed the Americas. In 1545, the richest silver deposit in history, the Cerro Rico de Potosí in southern Bolivia, was discovered on the traditional territory of the Charcas and Chullpas people (fig. 5). Extraction undertaken by the Spanish Empire initiated extraordinary movements of capital, knowledge, technology, and forced labor, forming a commodity frontier that would reshape systems of value globally. Extraction in Potosi was represented in maps, paintings, and engravings that were circulated worldwide. Mining had devastating socioecological effects. As filmmaker Harun Farocki describes: “The Spaniards brought the cross and took away the silver. In doing so, they almost exterminated the Indigenous population.”16 By the time photography was introduced to the world in 1839, silver mining was concentrated in the Americas.17 Throughout the nineteenth century, silver deposits were discovered throughout the Western United States, reshaping landscapes, displacing Indigenous communities, radicalizing workers, and giving rise to industrial dynasties, many of which would go on to fund art institutions, such as the Guggenheims.18

At the turn of the twentieth century, silver veins were discovered in Canada. In 1902, the Temiskaming and Northern Ontario Railway was chartered as a Crown corporation.19 The railway brought an influx of tourists north, but it was also intended to open up the region for agriculture, logging, and potential mineral exploration. In 1903, just as tourism was ramping up, railway workers discovered rich silver deposits in Cobalt, roughly fifty kilometers from Temagami. The mining camp had two major factors that facilitated its success: the ore was of incredibly high value coupled with a very low cost of extraction, and its geographic location was accessible by train from northeastern centers of industry in the United States. In 1903, Canada had no significant mining industry, and as a result it had very few homegrown miners, prospectors, or investors. With the discovery of silver in Cobalt, investors, mine owners, and workers traveled north from mining camps in the American West.

The first mine incorporated in the camp in 1905, The McKinley-Darragh-Savage Mine, had ties to the Eastman Kodak Company (EKC) in Rochester, New York.20 Indeed, several mines were capitalized by investors, or had owners or managers, from Rochester, including The Rochester Mine Cobalt, Limited; North Cobalt Silver Mines Company; The Genesee Mining Company, Limited; The National Mines, Limited; and The Hewitt Lake Mining Syndicate, among others. The Ottawa Citizen observed in 1906 that if Ontarians “had not been overcautious and incredulous during the past eighteen months they might have made a lot of money. Now the Americans are coming in and buying large interests in the camp.”21 In 1907, a syndicate headed by New York–based industrialists Daniel and Murray Guggenheim invested in the Nipissing Mine. Thomas Edison, the inventor of motion picture film, founded the Darby Mine in Temagami, although he was in search of the mineral cobalt for batteries, not silver for film stock.22 This cross-border movement of labor, capital, and resources transformed life in the region; it also proved problematic for the Teme-Augama land claims.

Speck in Temagami

Speck arrived in Temagami at a pivotal moment in the relationship between the Temagami band and the provincial government of Ontario. While the Saugeen Anishnabeg in the neighboring region of Timiskaming, Quebec, were granted a reserve in 1852, the Teme-Augama did not have a formal agreement with the provincial or federal government, and their rights to the territory were not recognized. The creation of the Temagami Forest Reserve in 1901 introduced a policy of forest management designed to balance logging and preservation. It did not take into account the Indigenous inhabitants of the territory whose rights were even further eroded as wilderness tourism, logging, and mining escalated over the first decade of the twentieth century. In contrast to salvage anthropologists, Duncan Campbell Scott, the deputy superintendent of the Department of Indian Affairs (DIA) from 1913 to 1932, saw little value in Indigenous cultures and advocated for assimilation. Reserves were also created in part to facilitate development. Specifically, Campbell Scott selected reserve lands that had no mineral deposits and would not interfere with “railway development or the future commercial interests of the country.”23

In 1913, the Teme-Augama believed that the government would finally grant them a reserve in Temagami.24 A week before Speck arrived, a meeting was held with federal officials to negotiate a reserve. However, because provincial officials did not attend, the negotiations were halted.25 It was in this context that Speck arrived in June 1913 to conduct fieldwork. Community members have recounted that the Teme-Augama believed Speck was there on behalf of the federal government to gather information that would help settle their land claim.26 While in Temagami, Speck collected ethnographic material for the Victoria Memorial Museum and documented the experiences and folklore of the community. He also worked on his theory of family hunting territory, which would prove to be controversial in the anthropological community, partly because it was suspected as being politically motivated by Indigenous communities.27 Speck’s deeply personal mode of participant observation, what he described as “bedside ethnography,” contributed to the perception that his research was not wholly objective.28 Speck’s approach to fieldwork, however, was productive. In correspondence with Sapir, Speck described the community as welcoming and forthcoming with information.29

The willingness of the community to provide information to Speck reflects that they believed it might be useful in helping them prove their claims to territory. Speck was a representative of the government, albeit not directly tied to the Department of Indian Affairs, yet he was sympathetic to their cultural traditions and their contemporary plight. Abenaki anthropologist Margaret M. Bruchac directs our attention to the ways in which the Teme-Augama provided information to Speck to advance their own agenda, highlighting the significant role played by Indigenous people in producing anthropological knowledge.30 The community was very aware that their rights were being reduced by the encroachment of settlement and extraction, and their participation in Speck’s anthropological research reflects a community actively shaping the production of knowledge about Indigenous life in this period.

Speck belonged to the first generation of anthropologists to follow Boas’s method of fieldwork, based on long stays within a community.31 While in Temagami, he took a number of photographs, most of which were taken in mid-August, near the end of his first trip. There are other photographs from a second trip in February 1914. The majority of the photographs in the collection are stamped and dated by the Department of Mines Geological Survey Photographic Division. Speck’s field photography is situated within an international anthropological practice that aimed for objectivity, but more often revealed contingency and ambiguity.32 Colleagues described Speck as the “greatest and most persistent fieldworker of all of Boas’ students,” and this shift in methodology is reflected in a more personal approach to image making.33 Handheld cameras give more agency to the subject than large-format cameras and allowed for snapshot photographs, facilitating a more intimate approach to anthropological knowledge production. This was aided by Speck’s proficiency with Indigenous languages and interest in their philosophies, prompting a widespread assumption among his colleagues, and repeated by his biographers, that he had “Indian blood” or had been raised by members of the Mohegan tribe.34

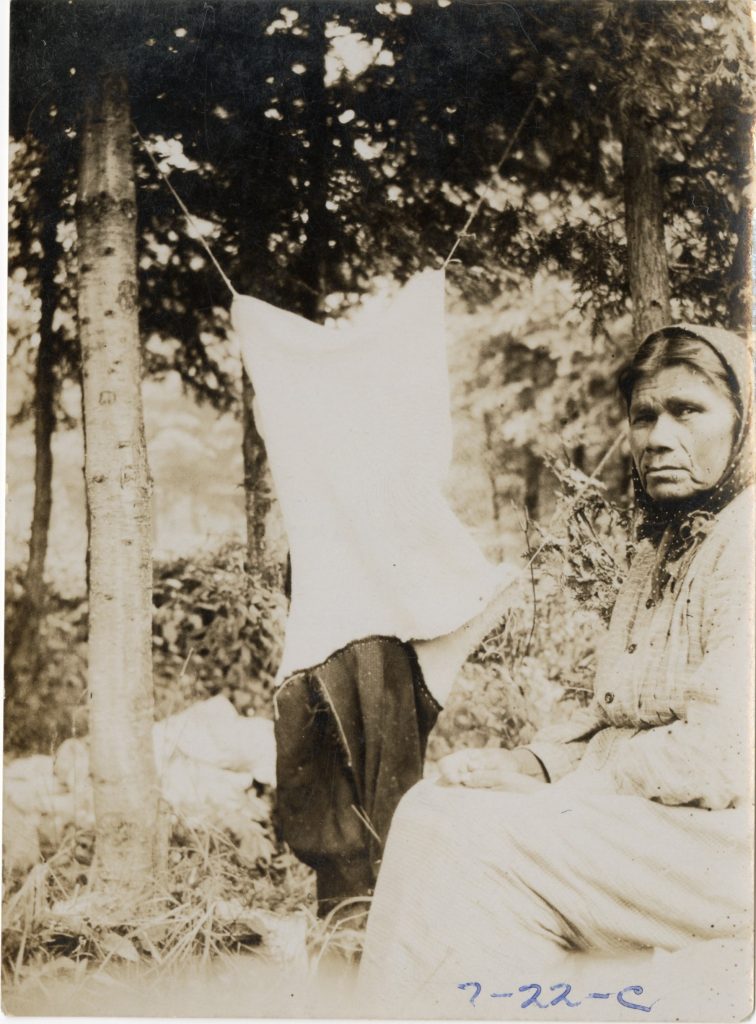

An archive of photographs documents Speck’s time with the Teme-Augama, including the real-photo postcard of the Indigenous boy holding Kodak film. These images subtly yet consistently articulate land use, demonstrating the multiple ways in which Indigenous communities reshaped their environments. For example, a photograph documents Peenay “Partridge” smoking a moose skin after tanning (figs. 6a,b). Partridge’s direct gaze at the camera, combined with the close framing of the image, creates an intimacy that mimics the intimacy of the labor, the slow and deliberate process of soaking and stretching the hide until it is soft and uniform. Tuscarora art historian Jolene Rickard describes how the material culture produced by Indigenous communities that is “molded in clay, carved in stone, stitched in animal skins, woven in fibers” reflects ongoing relationships with land.35 Unlike the stock images of Indigenous labor that circulated on lithographic postcards, the subject is named, and her labor is acknowledged.

The representation of labor connects to contemporary discussions surrounding land use that were employed to justify the settler colonial project. Throughout the Americas, settler states referenced terra nullius to argue that the land was empty because no one had shown the initiative to develop the land, and therefore it could be expropriated regardless of settlement. In the case of the Teme-Augama, making land productive meant the prioritization of logging and mining, limiting Indigenous access to their own territory. As Zapotec scholar Isabel Altamirano-Jimenez explains, this framing of lands “corresponded to a practice of eliminating Indigenous peoples . . . and the rejections of Indigenous land ownership.”36 In this context, the images within Speck’s archive that emphasize labor—splitting spruce tips, transportation by canoe, tanning a moose hide—take on a different resonance.

Under the guise of salvage anthropology and the GSC, the evidentiary nature of photography was enlisted to document traditional land use-patterns. At the same time, the small ruptures of stereotype within the photographs, such as the Kodak film being held by the longboat worker’s son, undermine the promise of unmediated glimpses into exotic ways of life, asserting that Indigenous labor coexists with the modern. This demonstrates that the extraction of Indigenous culture by settlers was not a linear process, as Indigenous communities responded to cultural imaginaries of authenticity, and points to the ways in which identity was always mediated and in flux. As cultural historian Sumathi Ramaswamy has suggested, we should “consider empire formation as a messy business of mutual entanglements and imbrications, of collisions and compromises,” placing enmeshment in the foreground instead of cultivating a binary understanding of active colonialists with agency acting upon passive or resistant colonized populations.37

Photographic Authenticity and Collaboration

At the turn of the twentieth century, images played an important role in shaping public opinion about what constituted authentic Indigenous identity. There was a fascination with authentic Indians, an existence that was perceived to be preindustrial, precapitalist, and therefore out of sync with the modern world. This belief informed a preoccupation with the imminent disappearance of the true Indian who could not coexist with modernity. This idea also served political goals of expansion onto Indigenous territory for settlement and/or industry. Photography was considered an important tool to document vanishing races, as in Edward S. Curtis’s The North American Indian, a twenty-volume set of photographs and text produced between 1907 and 1930. As feminist scholar Anne McClintock notes, while the authorial emphasis has been placed on Curtis, the body of work produced was “a huge collaborative enterprise in which Native Americans contributed significantly to the project as photographers—like his prodigious assistant Alexander Upshaw (Apsáalooke, 1874/5–1909)—interpreters, cultural brokers, cooks, and laborers.”38 The emphasis on collaboration can also be extended to the subjects of Curtis’s images, who were “to some degree at least, coauthors of the visual meanings,” highlighting agency and participation.39 This understanding of portraiture approaches photography as inherently collaborative: always a site of negotiation and interaction between photographer and subject.40

Anishinabekwe visual anthropologist Celeste Pedri-Spade has argued that while scholarship has traditionally placed emphasis on the intent and agency of the photographer, we “cannot presume that these individuals were solely the silenced subject or victim in a one-sided, inferior relationship with the camera and its operator.”41 They instead presented themselves to the camera in ways that asserted autonomy and agency. Significant numbers of Indigenous people engaged with modernity and technology to confront settler expectations that understood Indigeneity as anachronistic. For example, Ištá Ská (Oglala) was featured in a lithographic postcard of performers of “Buffalo Bill’s Wild West” on horseback in Paris in 1905. Ská sent one of these postcards to the French aristocrat Folco de Baroncelli, to whom he would also send real-photo postcards of the South Dakota landscape. Art historian Emily C. Burns documents how Ská embraced postcards and photocards to “test out identities along a spectrum between Oglala tradition and assimilation.”42 Indigenous performers created spaces of agency and alternative economies of cultural and economic survival. At the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition, Kwakwaka’wakw people from Vancouver Island performed a purported adaptation of a sacred winter ceremony that played with stereotypes of wild and savage Indians, what historian Paige Raibmon describes as a “show of cultural survival and political defiance.”43 Both Ská and the Kwakwaka’wakw performers used self-presentation as a site of self-determination.44

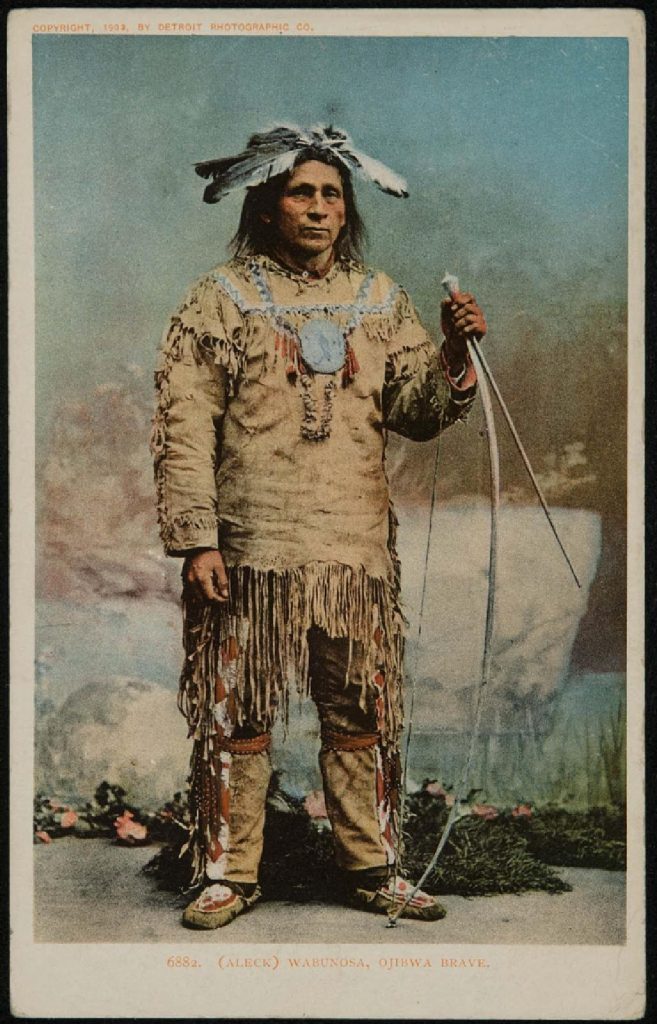

As the postcard of Ská demonstrates, images of Indigenous people in the Americas were popular subjects for postcards. Within Speck’s archive is a 1903 lithographic postcard produced by the Detroit Photographic Company that captures “(Aleck) Wabunosa, Ojibwa Brave” (fig. 7). Wabunosa poses in a yoke with beaded embroidery on top of a fringed buckskin shirt and knee-high moccasins, with a feathered headdress framing his long, loose hair. While other postcards from the same series show Ojibwa braves posing in action shots, Wabunosa stands in a dignified stillness in front of a studio backdrop. Holding a bow and arrow loosely in his right hand, he stares somberly out of the frame. The postcard does not follow an anthropological emphasis on cultural specificity and is one of only two mass-produced postcards archived in Speck’s collection of Temagami.45 The performative nature of the image stands in contrast with the ordinary, day-to-day scenes that Speck documented.

In tourist advertisements of Temagami, the promise of exposure to authentic Indigenous culture was a common theme. In postcards, however, Indigenous people often appeared as exotic, romantic, premodern figures. Extractive capitalism’s propensity “to abstract in order to extract” enacts a process of distancing that obscures historical and cultural specificity.46 This process often plays out in visual culture, demonstrated in the abstraction of people to types in postcards of “Indians.” Standardized, mass-produced, and cheap lithographic postcards such as those by the Detroit Photographic Company could be collected, catalogued, and compared by white settlers as a way of consuming Indigenous culture, forming a process of extraction. In this context, the reproducibility of the lithographic postcard is central to its meaning. The word “stereotype” comes from the printing trade and refers to a relief-printing plate used to reproduce identical copies.47 When applied to people, stereotypes produce generalized impressions of groups of people, which are then layered with symbolic meanings. Stereotypes create a set of expectations that direct our reading of images, which has tangible effects.

In 1903, the year the Ojibwa Brave postcard was made, Wabunosa was an actor in Hiawatha, a play developed by Garden River First Nation based on Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s The Song of Hiawatha.48 The performance was enacted by a “troupe of Ojibways from the North Shore of Lake Huron,” organized by L. O. Anderson and the Colonization and Tourist Agent of the Canadian Pacific Railway, and staged in various cities in the United States as part of the Sportsmen’s Show (a traveling expo). The show packaged Canadian identity for a US market to promote wilderness tourism, as the 1,200 foot constructed display of Canadian nature “showed wilderness in every inch.”49 In the promotional material for the performance, Wabunosa is identified as a guide from Garden River in Northwestern Ontario.50 Based on the fact that the postcard was taken the same year that Wabunosa appeared in Hiawatha, it is reasonable to assume that the attire and character were connected to the performance. The “Ojibwa Brave” was likely a performative construction of the “warrior,” context that is lost in the widespread circulation of the postcard.

The anthropologist Deborah Poole has drawn attention to the circulation of anthropological images in “image economies,” highlighting how the meanings of the images change through mobility.51 The idea of Indianness embodied in this postcard, in which an Indigenous man is literally playing Indian, participated in a visual economy of representing Indigeneity that could be appropriated by settlers. Dakota historian Philip Deloria has written that in the United States, playing Indian produced a sense of closeness to Indigeneity that enabled settler colonials to establish connections to territory.52 In Canada, Indigenous traditions were blended with French Canadian culture to create a native Canadian identity.53 Photography’s correlation with the performative assumption of identity is linked to the relationship between photography and the practice of staging, especially within the portrait studio. For example, William Notman and Company captured studio portraits of settlers dressed up in Indigenous regalia. The sets included props gathered indiscriminantly from different Indigenous communities across the country. An 1896 photograph captured the deputy superintendent general of Indian affairs, Hayter Reed (1893–97), dressed as Donnacona, the Iroquois chief.54 His costume mixed elements from Blackfoot and Cree communities to create a mythology of Indianness.55 Reed enacts a process of imagining an inheritance of Indigenous culture that functioned as a naturalization of the colonial project by allowing settler colonials to construct connections to territory.56

The symbolic construction of settler ties to land connects to assimilationist government policy. In his official capacity at DIA, Reed implemented policies that discouraged Indigenous people on the prairies from using farming equipment.57 In an ironic contrast to his studio costume representing traditional ways of Indigenous life, Reed believed that Indigenous communities should adopt subsistence agricultural methods used by farmers in Europe. This policy disrupted traditional land-use patterns. It also prevented communities from participating in market economies that required labor-saving machinery to make costs competitive, keeping communities in a state of economic underdevelopment. Under this assimilationist worldview, the violence against Indigenous people, the suppression of language and culture, and the expropriation of Indigenous territory were justified as inevitable steps in the linear progression of history. The cultural appropriation of Indigeneity is inextricably linked to the expropriation of Indigenous territory.

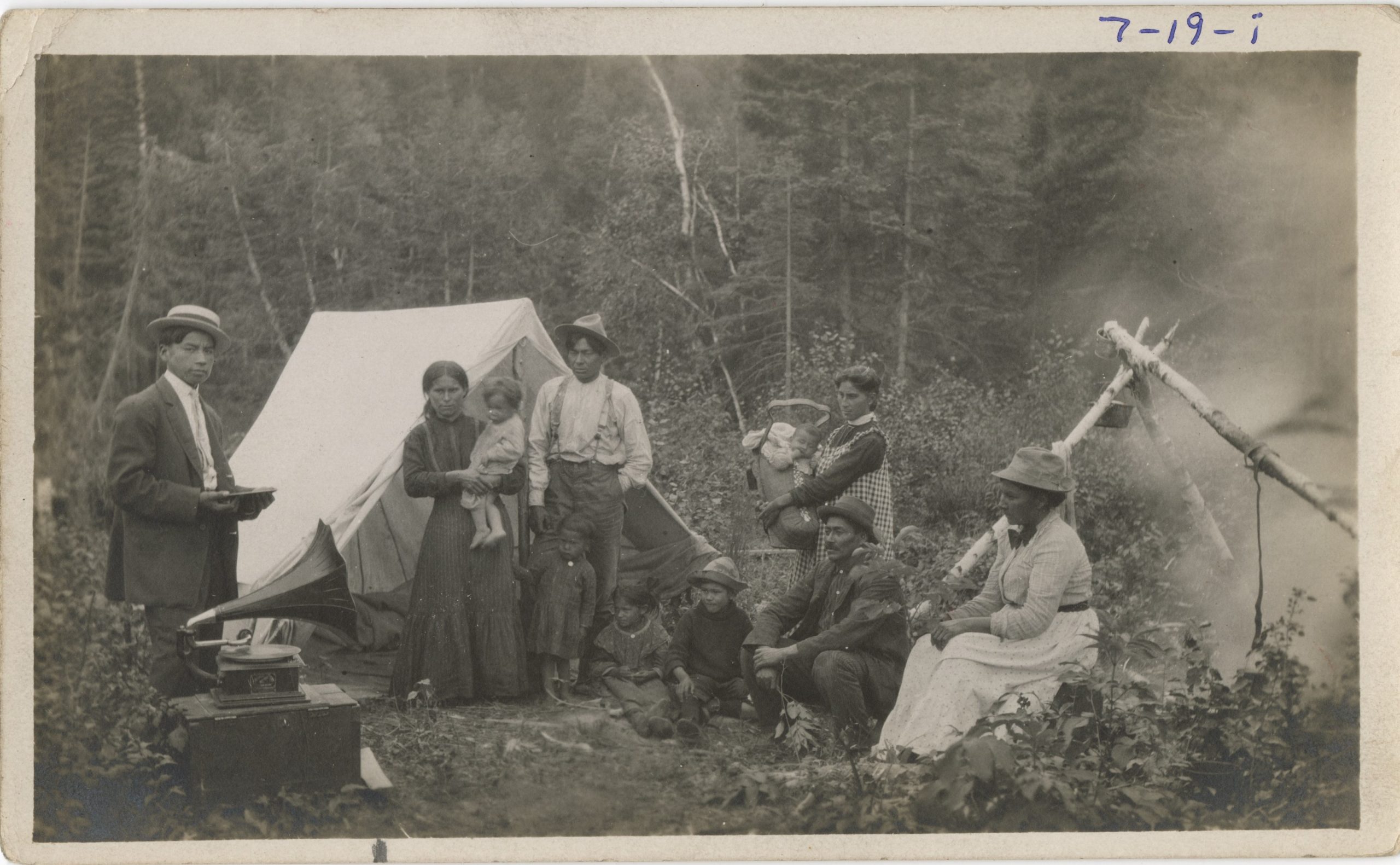

In contrast to the lithographic postcard of Wabunosa or the performance of Indigenous identity by settler colonials, a real-photo postcard in Speck’s album shows a group sitting in what appears to be a temporary campsite situated in a richly textured forest setting, a common motif in representations of Indigenous communities in the area (fig. 8). Speck’s postcard of the group in the campsite is a real-photo postcard. Real-photo postcards were individually printed in small numbers directly from negatives onto photo paper with a divided back and sent through the mail. Unlike traditional postcards, which often served to reinforce stereotypes, the ability to print any photograph as a postcard introduced the possibility for documenting, circulating, and archiving events of local significance.

The image captures the lushness of the foliage, while the framing immerses the viewer within nature. On the right-hand side, hazy smoke from a cooking fire pours out of a rudimentary structure made of birch trees; however, the attention of the group is directed away from cooking and toward a more modern leisure pursuit. The group faces the left-hand side of the frame, where a young man stands beside a phonograph holding a record. The presence of the phonograph invites us to imagine music filtering through the forest, forcing a reconsideration of the forest not as an untouched natural site or a retreat from the contemporary world but instead a place for work and play. The group’s modern clothing further asserts contemporaneity. The man on the far left is jauntily dressed in a boating hat and an oversized suit jacket. The woman on the far right wears long sleeves, a high collar wrapped in a bow, and a full polka dot skirt over a tight bodice, fixed with a leather belt; her companion dons a loose gingham garment and holds a baby in a cradle board.

The format of Speck’s postcard breaks from romantic, premodern renderings of Indigeneity that circulated in this region at that time. It undermines a widespread settler belief that Indigenous people had a naivete around technology—in this case around musical technology—but, in other instances, around image-making technologies. Narratives circulated that described how “supposedly primitive Indians are fearful of cameras, duped or coerced into film appearances, the subject of photographic jokes, so unsavvy that they refuse to play dead after being shot, and so on,” which suggested that Indigenous people were incapable of controlling their image and how it might be used.58 The Philadelphia Photographer described that “some of the Sioux think that photography is ‘pazuta zupa’ (bad medicine). Others have an impression that they will die in three days if they have their portraits taken.”59

As white settlers imagined an authentic Indigenous identity, Indigenous people occasionally toyed with stereotypes to assert their right to engage modernity and tradition equally. The postcard of the phonograph in the forest demonstrates how the mandate of salvage anthropology was nuanced in the interaction between the anthropologist and the community. While this is not to imply that power imbalances did not exist between the community and the state, as well as between the anthropologist and the subjects of the photographs, it does indicate that as the Teme-Augama presented themselves to the camera, an alternative perspective is introduced that asserted their ongoing connection to territory.

Contesting Terra Nullius

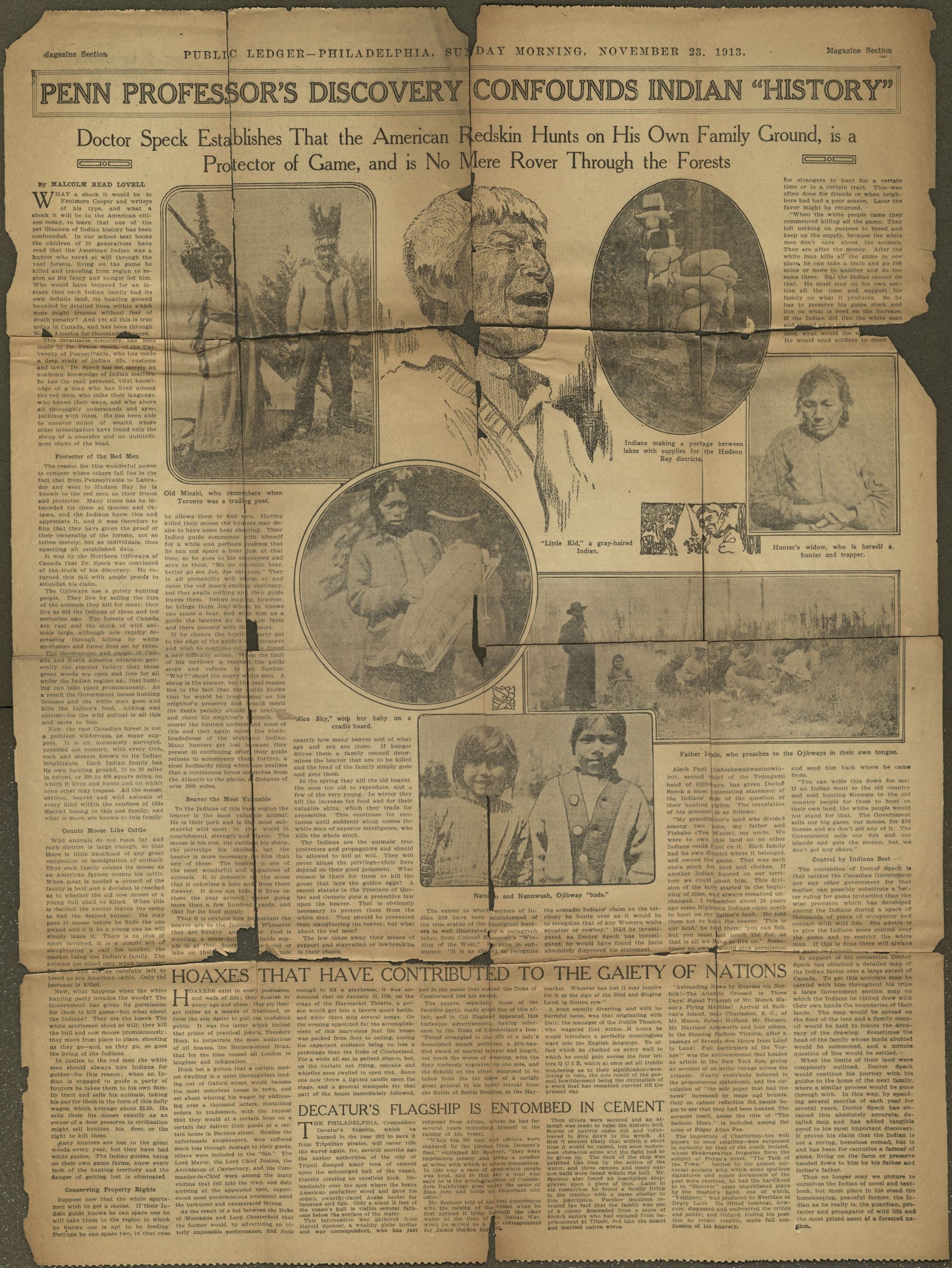

A few months after Speck’s fieldwork in Temagami, six photographs and two illustrations were published in the Philadelphia-based Public Ledger, illustrating an article titled, “Penn Professor’s Discovery Confounds Indian ‘History’: Doctor Speck Establishes That the American Redskin Hunts on His Own Family Ground, is a Protector of Game, and is No Mere Rover Through the Forests.”60 Occupying a full broadsheet, the article by Malcolm Read Lovell outlined Speck’s research on the hunting territory of the Teme-Augama (fig. 9). The article suggests that Speck’s research disproves the doctrine of terra nullius, conclusively demonstrating through rich fieldwork that “the vast Canadian forest is not a pathless wilderness, as many suppose. It is an accurately surveyed, parceled out country, with every tree, rock and stream known to its Indian inhabitants.”61 Lovell presents Speck’s research uncritically, describing Speck as the “Protector of the Red Men” and celebrating his “invaluable discovery.”62

Speck argued that his research demonstrated the ongoing and unbroken regulation, maintenance, and control of territory by the Teme-Augama. The portraits show members of the Teme-Augama band: children, a mother with a baby on a cradleboard, and elders. The photographs function as evidence of multigenerational Indigenous connections to territory. These portraits are included alongside a photograph of a priest, Father Evain, preaching “to the Ojibways in their own tongue” and another shot of “Indians making a portage between lakes with supplies for the Hudson Bay districts.” All of the images are simple in their framing and ordinary in the subject matter. The group shots and portraits of people doing day-to-day tasks reflect their ongoing presence in this territory, or “survivance.”63

A quotation in the article from Chief Aleck Paul situates the central conflict over territory as being one of extractivism:

They [white settlers] are after the money. After white man kills all the game in one place, he can take the train and go three hundred miles or more to another and do the same there. But the Indian cannot do that. He must stay on his own section all the time and support his family on what it produces.64

Paul argued that white settlers were endangering the community’s way of life by depleting ecosystems, which stood in contrast to the conservation and ongoing maintenance of land by the Teme-Augama. Through the direct challenge to terra nullius, Paul undermines settler colonial assertions that the land was empty and waiting for their extractive presence to make it productive. It is worth noting that Paul asked Speck to advocate to the Canadian government for their territorial rights.65 This advocacy is included in the article, which notes that Speck’s “advice [to the Canadian government] is to give the Indians more control over the game and to restrict the white man.”66

Speck’s research sought to convert Indigenous oral traditions into a framework of private property that the Canadian government would recognize as legitimate. This draws attention to the link between what counts as knowledge and who has the power to record and produce knowledge. Speck used settler ideologies of land use—arguing that territory was individually managed by Indigenous families and therefore conformed to Western notions of property—but in a way intended to benefit the community. His research “conceptually secularized hunting practices into a modern model that (apparently intentionally) fit the restrictions of the 1876 Indian Act.”67 Despite the specific implications of this research for Canadian governmental policy, the article was published in the United States, which highlights the cross-border significance of the research. The framing of the article links discussions of terra nullius in the US to Speck’s research in Canada, observing “what a shock it would be to Fenimore Cooper and writers of his type, and what a shock it will be to the American citizen of today,” suggesting that this research done on Indigenous connections to territory in Canada had broader hemispheric relevance.68

Speck later expressed disappointment that his research did not influence policy-makers to stop the dispossession of Indigenous people.69 His photographs play a nuanced and ambiguous role in an anthropological project initiated by the state with direct ties to extraction, revealing what Gómez-Barris describes as a “submerged perspective” that exists alongside the extractive gaze.70 These latent perspectives deny any sole ownership of the images or their meanings, and these images cannot simply be reduced down to the colonial-extractive gaze of the GSC. Speck’s photographs shifted meanings as they moved between the private (the album) and the public (the archive and the newspaper). As a result, the photographs register at multiple levels. They form a record of Speck’s time in the community, a private research archive for further consultation, and presumably, carried an affective resonance for Speck. In the public dissemination in a newspaper, Speck utilizes the images in the context of political advocacy. These images also, however, have meaning to the individuals and communities documented that exist outside of the formation, archiving, or intent of the images. They draw attention to a parallel history that counters the extractive gaze which existed before, during, and after extraction, an assertion of presence that resisted displacement. The archive reveals the other histories, stories, and purposes of the extractive zones that supplied the silver that was set in images worldwide.

Reactivating Histories

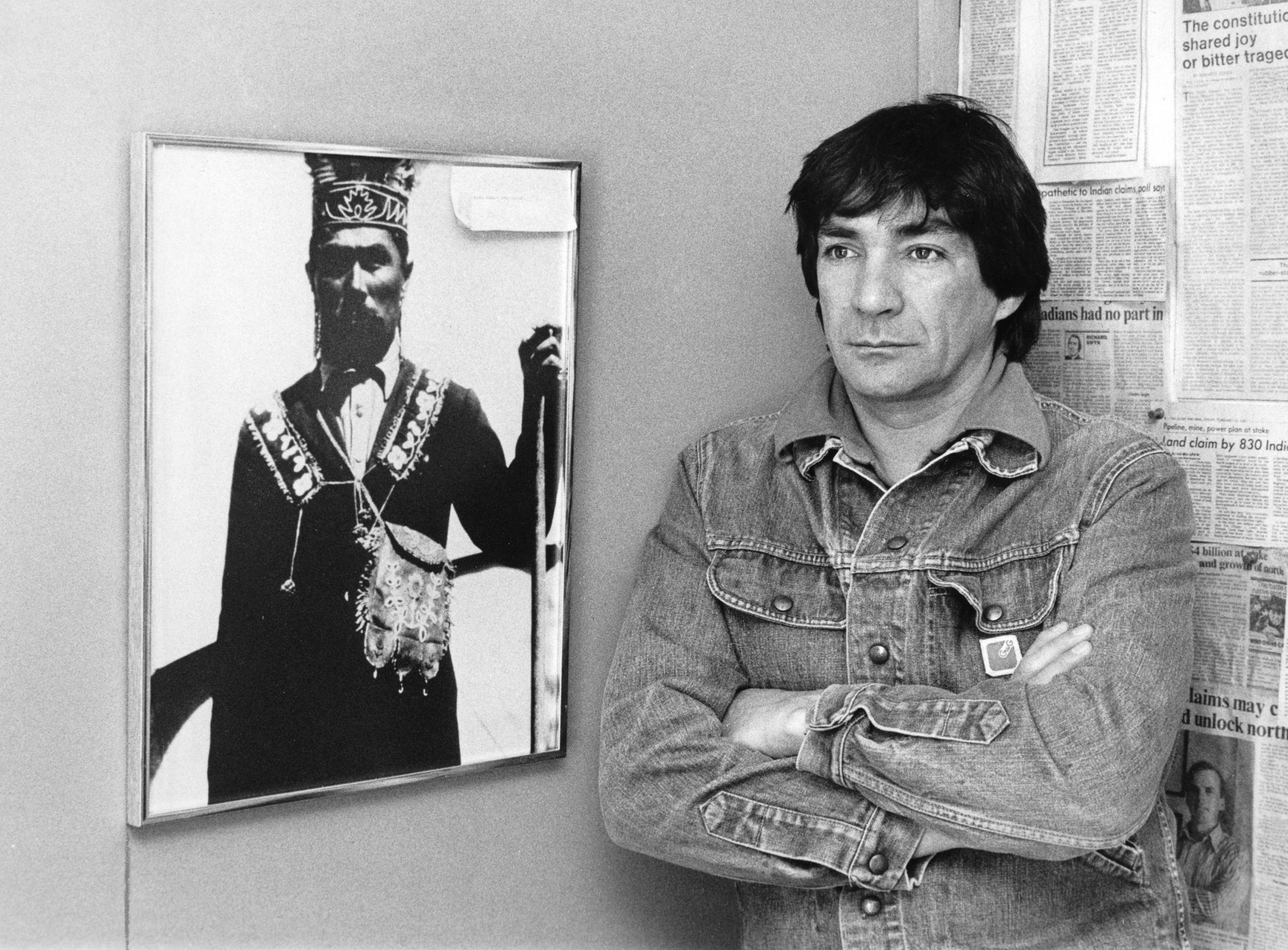

More recently, Indigenous communities have reanimated anthropological images in a practice of image use that locates connections through time.71 This reactivation of histories is shown in a 1983 portrait of Gary Potts, then the chief of the Teme-Augama First Nation (fig. 10). He leans against a wall covered in newspaper clippings. Beside him is a large framed 1913 photograph of Chief Aleck Paul. The image is similar to photographs of Paul taken by Speck and is presumably from the same fieldwork trip. Potts is dressed casually in a denim jacket, while Paul presents in regalia, holding a staff. Both, however, convey the authority of their position. The camera is angled so that the photograph of Paul—who, in the 1913 photograph, addresses the camera directly—appears to look at the viewer. In Speck’s archive of the Teme-Augama, there is an openness to the way that people present to the camera. This openness likely reflects a level of comfort with Speck but also the reality that they thought that Speck could help them by translating their experiences into a framework that was recognized as legitimate by both anthropologists and the Canadian government.

Paul’s body language forms a contrast to Potts. In a refusal to perform for the camera, Potts angles his body away from the lens with his arms crossed, defiant and determined. This shift in self-presentation reflects changing dynamics and strategies. In 1913, the community believed that the government would settle their land claim. As Potts reflected on Speck, “Our people called him the writing man, and they told him the whole story of the Teme-Augama Anishnabai.”72 It was nearly sixty years after Speck’s visit that the province of Ontario granted the Teme-Augama a reserve of one square kilometer on Bear Island. In response to the inadequacy of the government’s offer, Potts escalated the community’s tactics in a way that directly disrupted the priorities of the settler state. In August 1973, Potts filed paperwork with the land registry office to issue a land caution on ten thousand square kilometers of Ontario crown land. Land cautions pause development in the context of competing mining claims. Once a caution is issued, land cannot be sold or developed until the legal ownership of territory is decided. The land caution halted all new development—including mining, logging, and a theme park—on Crown land for over twenty years as the case snaked through the courts.73 The Teme-Augama argued that since they were not signatories of the Huron-Robinson Treaty, they had not relinquished their traditional territory to the Crown. Speck’s research was used to advocate for their right to what they called N’Daki Menan, “our land.”74

Using a legal mechanism developed to protect property in the context of extraction, the Teme-Augama asserted their claim over territory that predated colonial borders. The filing of the land caution connects directly to the issues that the Teme-Augama articulated sixty years prior. In both instances, the issue was not only about ownership of land but how the land is used. Potts described the bureaucratic language of “sustained development,” which functioned as a “rubber stamp to go ahead and develop what’s left of earth.”75 In contrast, the community advocated for “‘sustained life,’” which included the “non-human voice.” In 1991, the Supreme Court of Canada rejected the land claim, ruling that while the Teme-Augama had never signed the treaty, they had adhered to it in practice; however, the court also ruled that the Crown had breached its treaty and fiduciary obligations, affirming the Teme-Augama had aboriginal title or right to territory. The land caution was not lifted until 1996.

The double portrait of Potts and Paul moves outside of colonial boundaries and across time periods and links the two chiefs and their advocacy for the Teme-Augama. Potts’s gaze is intense but focused beyond the horizon. It suggests an orientation toward the future, although his defensive posture also reflects a community under pressure. Potts remained defiant in the face of the Supreme Court ruling, reflecting that the struggle would go on, for it was driven by “a spirit that rises from the Canadian soil . . . they cannot suppress the Indigenous spirit . . . and the Canadian people have nothing to fear from that.”76

In Conclusion

In the Americas, the hemispheric circulation of knowledge, labor, and capital shaped the mining industry while images symbolically affirmed the value of extraction and wealth production. The development of mining and logging in the region was extensively documented in photographs by governments, corporations, and individuals, although the ecological and social devastations that accompanied extraction are not visible in Speck’s fieldwork photographs of Temagami. The material transformations in Indigenous life in this period, including their displacement from traditional territory and the limitations on traditional land-use patterns, however, are tied to the encroachment of logging, mining, and settler colonialism. In this context, the Teme-Augama worked with Frank Speck to prove their land title. As anthropologist Ann Laura Stoler reflects, archives are sites of “epistemological and political anxiety,” and Speck’s fieldwork, tied as it was to the GSC and territorial control, is an archive that sits uneasily with “predictable stories with familiar plots,” revealing the “granular rather than seamless texture” of the archive.77 Using photography as a tool, the Teme-Augama asserted their ongoing and unbroken connection to territory, laying bare the myth of vanishing races. In drawing attention to histories of territory that predate the nation state, the Teme-Augama denaturalize the concept of a distinctive national history of photography. By positioning their actions as being rooted in the enduring relationship to this territory, the images assert the ways in which Teme-Augama Anishnabai sovereignty exists outside of the state recognition of it.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council and the American Philosophical Society. I would like to express my gratitude to Adrianna Link, Patrick Spero, and Brian Carpenter.

Cite this article: Siobhan Angus, “Frank Speck in N’Daki Menan: Anthropological Photography in an Extractive Zone,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 6, no. 2 (Fall 2020), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.10820.

PDF: Angus, Frank Speck in N’Daki Menan

Notes

- Soaphy Anderson, “Canada’s Greatest Archipelago,” Mer Douce 2 (September/October 1921): 11. ↵

- Macarena Gómez-Barris, The Extractive Zone: Social Ecologies and Decolonial Perspectives (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2017), 5. ↵

- Speck was not an official employee of Sapir’s division, and Speck’s research for the GSC was informally arranged. The majority of Speck’s fieldwork was done on his own and partially financed by the sale of items collected in the field. ↵

- In this article, although the photographer is unidentified, I am working under the assumption that Speck was the photographer. ↵

- After Speck’s death in the 1950s, many of his papers and the majority of his photography collection was acquired by the American Philosophical Society (APS) in Philadelphia. The collection at APS consists of five thousand items, primarily from Speck’s own collection, including a set of four hundred lantern slides which were used for lectures and public talks. The collection was indexed by Anthony F. C. Wallace, an anthropologist and former student of Speck. Speck’s notes did not have a consistent organization, and it is unclear how much of the current archival system was imposed by Wallace. There are also photographs from regions in which Speck did not conduct fieldwork, including Mexico, South America, Africa, Asia, Australia, and Oceania. ↵

- Margaret M. Bruchac, Savage Kin: Indigenous Informants and American Anthropologists (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2018), 168. ↵

- For an analysis of extraction, vision, and world-making, see Gómez-Barris, The Extractive Zone; Marisol de la Cadena, “Uncommoning Nature,” e-flux, 2015, ccessed on October 4, 2020, http://supercommunity.e-flux.com/texts/uncommoning-nature. ↵

- Gómez-Barris, The Extractive Zone, 1. ↵

- Terra nullius is land that is legally understood as being empty or not being used. Terra nullius was commonly invoked by European settlers in the Americas to argue that Indigenous people did not have an entitlement to land and that it could expropriated. ↵

- Christopher Pinney, Photography and Anthropology (London: Reaktion Books, 2011), 17. ↵

- The department is now titled Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada. ↵

- E. Hall, Early Canada: A Collection of Historical Photographs by Officers of the Geological Survey of Canada (Ottawa: Queen’s Printer, 1967), 6. ↵

- For a history of the Geological Survey of Canada, see Suzanne Zeller, Inventing Canada (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2009). ↵

- For a contemporary description of this belief and method, see, for example, Franz Boas, “Ethnological Problems in Canada,” Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland 40 (1910): 539. ↵

- Robin Kelsey, “Photography and the Ecological Imagination,” in Nature’s Nation: American Art and Environment, exh. cat., ed. Alan C. Braddock and Karl Kusserow (Princeton: Princeton University Art Museum in association with Yale University Press, 2018), 394. ↵

- In his 2010 video essay, The Silver and the Cross, Harun Farocki analyzes a painting by Gaspar Miguel de Berrios (1706–1762) to develop a discourse on the socioecological consequences of extraction at Potosi, as quoted in Laura Turner Igoe, “Creative Matter: Tracing the Environmental Context of Materials in American Art,” in Nature’s Nation, 148. ↵

- Between 1550 and 1800, Latin America produced 80 percent of the world’s supply of silver. See Nicholas A. Robins, Mercury, Mining, and Empire: The Human and Ecological Cost of Colonial Silver Mining in the Andes (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2011), 4. Between 1870 and 1900, the United States and Mexico were responsible for over 50 percent of the global silver production. See Patrick Manning, Dennis O. Flynn, and Qiyao Wang, “Silver Circulation Worldwide: Initial Steps in Comprehensive Research,” Journal of World-Historical Information 3/4, no. 1 (2016/2017): 7. ↵

- Joel Conarroe. “Guggenheim, Simon (1867–1941), Mining Industry Leaders, Philanthropists,” American National Biography Online, Oxford University Press, February 2000, accessed on July 4, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1093/anb/9780198606697.article.1500298. ↵

- The region is referred to as both Timiskaming and Temiskaming. Temagami is also sometimes spelled as Timagami or Ti Magami. ↵

- Douglas Baldwin, Cobalt (Charlottetown, PE: Indigo Press, 2016), 15; and The Canadian Mining Journal (Toronto: The Mines Publishing, 1910), 8. ↵

- “Cobalt,” Canadian Mining Review 27, no. 6 (1906): 202. ↵

- Edison also discovered and abandoned the Falconbridge Claim in Sudbury, ON, which became one of the largest nickel producers in history. ↵

- Richard H. Bartlett, “Mineral Rights on Indian Reserves in Ontario,” Canadian Journal of Native Studies 3, no. 2 (1983): 253. ↵

- While the territory fell under the boundaries of the Robinson-Huron Treaty (1850), for reasons that are not entirely clear, the Teme-Augama were not invited to sign the treaty. The community claimed ten thousand square kilometers as their traditional territory. In 1943, a small island in the middle of Lake Temagami, Bear Island, was purchased by the Department of Indian Affairs from the Province of Ontario, in order to be designated as a permanent reserve. A reserve of one square kilometer was granted in 1971. ↵

- Gary Potts, “Bushman and Dragonfly,” Journal of Canadian studies 33, no. 2 (1998): 190. ↵

- Gary Potts and James Morrison, “The Temagami Ojibway, Frank Speck and Family Hunting Territories,” paper presented at the American Society for Ethnohistory Conference, Williamsburg, VA, November 11, 1988. ↵

- Janet Chute, “Frank G. Speck’s Contributions to the Understanding of Mi’kmaq Land Use, Leadership, and Land Management,” Ethnohistory 46, no. 3 (1999): 488. ↵

- Margaret M. Bruchac, “The Speck Connection: Recovering Histories of Indigenous Objects,” Penn Museum Blog, May 20, 2015, https://www.penn.museum/blog/museum/the-speck-connection-recovering-histories-of-indigenous-objects; and Chute, “Frank G. Speck’s Contributions to the Understanding of Mi’kmaq Land Use, Leadership, and Land Management,” 488. ↵

- Siomonn Pulla, “Anthropological Advocacy? Frank Speck and the Mapping of Aboriginal Territoriality in Eastern Canada, 1900–1950” (PhD diss., Carleton University, 2006), 237. ↵

- Bruchac, Savage Kin, 169. ↵

- Anthony F. C. Wallace, “The Frank G. Speck Collection,” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 95, no. 3 (1951): 286. ↵

- Elizabeth Edwards, Raw Histories: Photographs, Anthropology and Museums (Oxford, NY: Berg, 2001), 144. ↵

- William Fenton, “Frank G. Speck’s Anthropology,” in The Life and Times of Frank G. Speck, ed. Roy Blankenship (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, 1991), 9. ↵

- In a period of social stratification and racial prejudice, Speck’s willingness to associate socially with people from diverse backgrounds and his perceived preference for associating with Indigenous people rather than his colleagues form a large component of his reputation. As Margaret M. Bruchac describes, “Speck was an opportunist and a sort of ethnographic shape-shifter, willing to participate in whatever strange fictive kinship would offer him the best access to desired material or data. Native people welcomed him because he was generous, kind, and nonjudgmental. He allowed his white colleagues to imagine he had Native ancestry or Native kin, perhaps as a means to explain his desire to cross social color lines, or to avoid compliance with white social norms.” See Bruchac, Savage Kin, 149. ↵

- Jolene Rickard, “Arts of Dispossession,” in Picturing the Americas: Landscape Painting from Tierra Del Fuego to the Arctic, exh. cat., ed. Peter John Brownlee, Valeria Piccoli, and Georgiana Uhlyarik (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2015), 115. ↵

- Isabel Altamirano-Jimenez, Indigenous Encounters with Neoliberalism: Place, Women, and the Environment in Canada and Mexico (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 2014), 32. ↵

- Sumathi Ramaswamy, “The Work of Vision in the Age of European Empires,” in Empires of Vision: A Reader, ed. Martin Jay and Sumathi Ramaswamy (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2013), 4. ↵

- Anne McClintock, “Ghostscapes from Forever War,” in Nature’s Nation, 277. ↵

- Shamoon Zamir, The Gift of the Face: Portraiture and Time in Edward S. Curtis’s The North American Indian (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2014), 3. ↵

- From the inception of the medium, women and people of color used the “pseudo-scientific authority {of photography} to carefully craft stronger public personae.” See Sarah Parsons, “Site of Ongoing Struggle: Race and Gender in Studies of Photography,” in Gil Pasternak, The Handbook of Photography Studies (London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2020), 273. ↵

- Celeste Pedri-Spade, “‘But They Were Never Only the Master’s Tools’: The Use of Photography in de-Colonial Praxis,” AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples 13, no. 2 (2017): 106. ↵

- Emily C. Burns, Transnational Frontiers: The American West in France (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2018), 119. ↵

- Paige Raibmon, Authentic Indians: Episodes of Encounter from the Late-Nineteenth-Century Northwest Coast (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2005), 15. ↵

- For studies that focus on how the visual functions as a form of political self-construction for Indigenous North Americans, see Philip Deloria, Indians in Unexpected Places (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2004); Michael D. McNally, “The Indian Passion Play: Contesting the Real Indian in ‘Song of Hiawatha’ Pageants, 1901–1965,” American Quarterly 58 (March 2006): 105–36; L. G. Moses, Wild West Shows and the Images of American Indians, 1883–1933 (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1996); and Laura L. Peers, Playing Ourselves: Interpreting Native Histories at Historic Reconstructions (Lanham, MD: AltaMira Press, 2007); and Raibmon, Authentic Indians. ↵

- The other postcard captures “The Hudson’s Bay Post, Bear Island, Temagami, Ont., Canada,” about 1907. ↵

- Rob Nixon, Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2011), 41. ↵

- Deloria, Indians in Unexpected Places, 8. ↵

- For a discussion on resistance and representation in the Hiawatha performances, see Karl Hele, “The Vanishing Indians That Never Were,” Restorying Canada, accessed July 16, 2020, https://restoryingcanada.com/karl-hele. ↵

- Charles Hallock and William A. Bruette, “The Sportsmen’s Show,” Forest and Stream 60 (1903): 173; and Charles Hallock and William A. Bruette, “Chicago and the West: Chicago Sportsmen’s Show,” Forest and Stream 58 (1902): 128. ↵

- Hallock and Bruette “Chicago and the West,” 128. ↵

- Deborah Poole, Vision, Race, and Modernity: A Visual Economy of the Andean Image World (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1997). ↵

- Philip Deloria, Playing Indian (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998). ↵

- Gillian Poulter, Becoming Native in a Foreign Land: Sport, Visual Culture, and Identity in Montreal, 1840–85 (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 2009), 10. ↵

- J. Topley, Hayter Reed as Donnacona with his stepson Jack Lowery, Ottawa, 1896. National Archives of Canada, PA-139841, accessed October 4, 2020, https://www.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/CollectionSearch/Pages/record.aspx?app=FonAndCol&IdNumber=3191522. ↵

- Cynthia Cooper, Magnificent Entertainments: Fancy Dress Balls of Canada’s Governors General 1876–1898 (Fredericton, NB; Hull, QC: Goose Lane Editions; Canadian Museum of Civilization, 1997). ↵

- Poulter, Becoming Native in a Foreign Land, 125. ↵

- Sarah Carter, “Two Acres and a Cow: ‘Peasant’ Farming for the Indians of the Northwest, 1889–97,” The Canadian Historical Review 70, no. 1 (1989): 27–28. ↵

- Deloria, Indians in Unexpected Places, 54. ↵

- As quoted in “Photography Amongst the Red Indians,” Photographic News, September 14, 1866, 443. ↵

- Malcolm Read Lovell, “Penn Professor’s Discovery Confounds Indian ‘History’: Doctor Speck Establishes That the American Redskin Hunts on His Own Family Ground, is a Protector of Game, and is No Mere Rover Through the Forests,” Public Ledger, November 23, 1913, n.p. American Philosophical Society, Frank G. Speck Papers Mss.Ms.Coll.126, II(3B1k). ↵

- Lovell, “Penn Professor’s Discovery Confounds Indian ‘History,’” n.p. ↵

- Lovell, “Penn Professor’s Discovery Confounds Indian ‘History,’” n.p. ↵

- Gerald Vizenor, Manifest Manners: Narratives on Postindian Survivance (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1999), vii. ↵

- rank G. Speck, “Ojibwa Hunting territories,” n.d., American Philosophical Society, Frank G. Speck Papers, Mss.Ms.Coll.126, II(2F5) Ojibwa Hunting territories, 3. ↵

- Bruchac, Savage Kin, 168. ↵

- Lovell, “Penn Professor’s Discovery Confounds Indian ‘History,’” n.p. ↵

- Bruchac, Savage Kin, 168. ↵

- Lovell, “Penn Professor’s Discovery Confounds Indian ‘History,’” n.p. ↵

- Harvey A. Feit, “Afterword: Dispossession with Possession, Governance with Colonialism: Algonquian Hunting Territories and Anthropology as Engaged Practice.” Anthropologica (Ottawa) 60, no. 1 (May 2018): 151. ↵

- Gómez-Barris, The Extractive Zone, 1. ↵

- Elizabeth Edwards, “Photographs and the Sounds of History,” Visual Anthropology Review 21, nos. 1/2 (2005): 28. ↵

- Potts, “Bushman and Dragonfly,” 190–91. ↵

- David McNaab, No Place for Fairness: Indigenous Land Rights and Policy in the Bear Island Case and Beyond (Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2009), 40. ↵

- Jocelyn Thorpe, Temagami’s Tangled Wild: Race, Gender, and the Making of Canadian Nature (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 2012), 126. ↵

- Potts, “Bushman and Dragonfly,” 188–89. ↵

- As quoted in Rudy Platiel, “Temagami Chief Gary Potts led fight for Indigenous rights to Northern Ontario land,” Globe and Mail, July 10, 2020. ↵

- Ann Laura Stoler, Along the Archival Grain: Epistemic Anxieties and Colonial Common Sense (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2009, 50. ↵

About the Author(s): Siobhan Angus is Banting Postdoctoral Fellow in the History of Art at Yale University