Pendant Across Time: John Singleton Copley and John Singer Sargent

PDF: Culp, Pendant Across Time

In 1899, the famed expatriate American painter John Singer Sargent (1856–1925) received an unusual commission. He was asked to create the belated twin to a much older work. By that point in his thriving career, Sargent had already painted many companion paintings, called “pendants,” in the standard style: matching portraits of a married couple, produced at or around the same period, framed independently, and displayed as a pair. In this configuration—a form descended from the diptychs of church altarpieces—the two physically separate images communicated their togetherness through compositional harmonies and reciprocal narratives. But the commission Sargent completed in 1900 was a different sort of request, requiring the artist to mirror a work by John Singleton Copley (1738–1815) from 1786. Such a pendant was unusual: it did not just marry two pictures across the expanse of wall space that divided them, as was traditional. What made it altogether different was that Sargent’s pendant attempted to fuse 1786 with 1900, linking two points in time.

This untraditional pendant was made with care and calculation. “What I want,” demanded the commissioner Sir George Sitwell (1860–1943)—4th Baronet, member of Parliament from 1885 to 1895, and owner of extensive grounds at Renishaw Hall in Derbyshire—is “a portrait group that will give information and tell its own story, and will hang and mezzotint as a pair to the Copley.”1 With characteristic peremptoriness, Sir George Sitwell referenced a group portrait completed over a century before. “The Copley” to which he referred—Copley’s six-foot-wide The Sitwell Children—was still on display in the dining room at the family seat, Renishaw Hall (1786; fig.1).2 By then an antique, it depicts a sprightly group of carousing children. The young Sitwells are directed by Sir George’s great-grandfather—named Sitwell Sitwell—and include, as well, his great-aunt Mary Sitwell and great-uncles Francis and Hurt Sitwell. For Sir George Sitwell, the success of his twentieth-century commission was contingent on its similarity to this Copley original. So he arranged for the 1786 painting to be wrapped, packed, and transported more than 150 miles south from Renishaw Hall to Sargent’s studio in London.

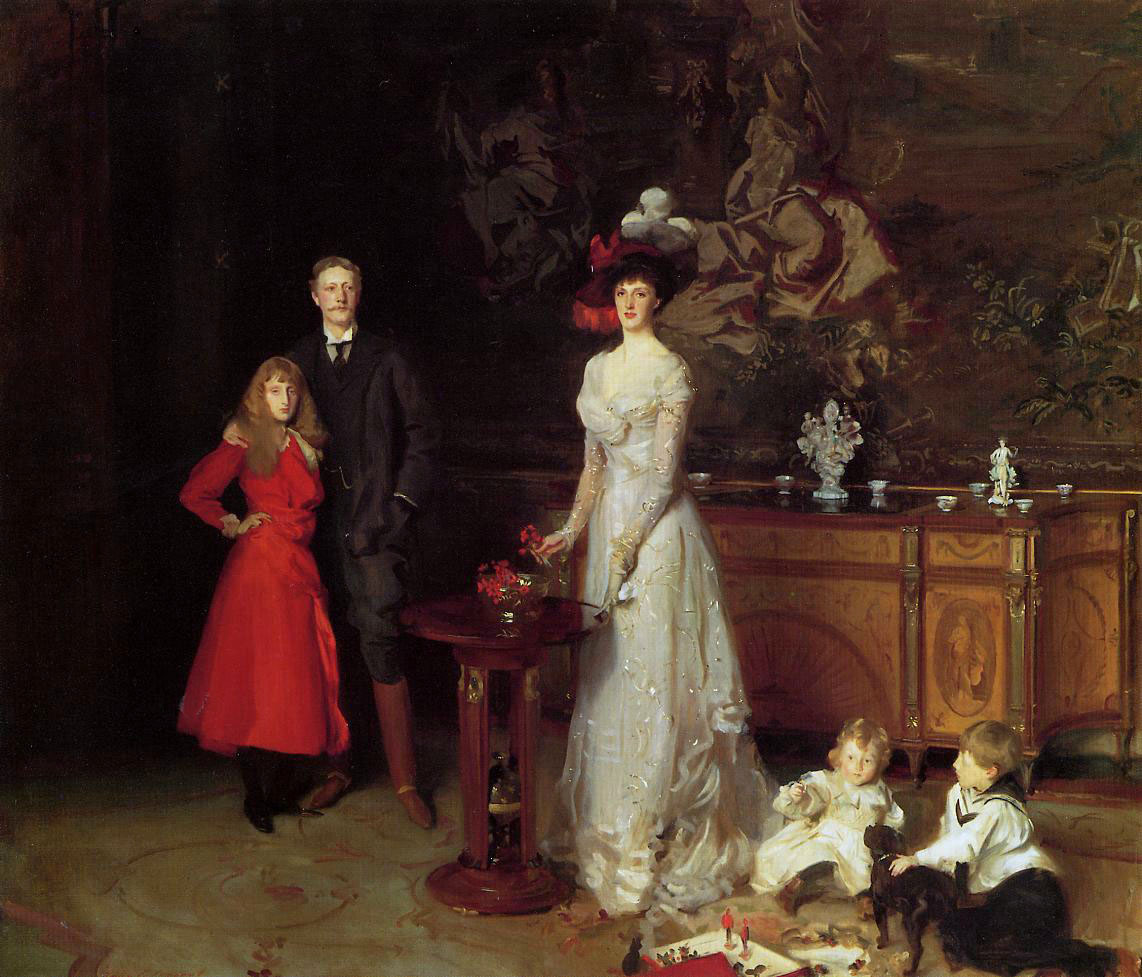

With the Copley canvas installed in his studio as both model and muse, Sargent took great care to reformulate many of the elements of its progenitor. The painter especially embraced his role in selecting the family’s costumes—apparently the one pictorial element wherein he was given free rein by the otherwise overbearing Sir George.3 Sargent’s resultant George Sitwell, Lady Ida Sitwell and Family (1900; fig. 2) intentionally mirrors the scale, palette, figural composition, and setting of the Copley. Sir George; his wife, Lady Ida; and their three children, Edith, Osbert, and Sacheverell, were painted as the iconographic doubles of their direct ancestors.

Considered together, Copley’s playfully boisterous group and Sargent’s more staid one evidence a bevy of rhyming elements. They are so similar, in fact, that a general description can serve to introduce both images. At the pinnacle of the roughly triangular figural group stands a female figure clad in white, her body serving as the visual anchor for the arrangement of forms within the frame. Connected to this central figure is a gentleman in riding boots and tight britches and a younger child dressed in flashing cardinal red. On the floor, interrupted games are strewn across the patterned carpet, their inclusion adding a sense of unaffected jocularity. The figures are positioned in interior rooms illuminated with natural light, surrounded by the decorative props of domestic life: a table, some flowers, and wall hangings.

The objects in Sargent’s George Sitwell, Lady Ida Sitwell and Family evidence the same special attention to the project of matching or doubling the two generations across the time that divides them. When he planned Sargent’s group picture of himself and his family, Sir George chose to include behind them an arrangement of family heirlooms, all of which originated from the era of Copley’s painting. Sir Osbert Sitwell, one of the boys playing on the ground in Sargent’s painting of 1900, would later describe these objects in his 1944 autobiography:

a vast and dark panel of Brussels tapestry, measuring thirty by twenty feet . . . a so-called commode, designed by Robert Adam, and executed by Chippendale and Haigh, with ormolu mountings by Matthew Boulton—a large and exquisite piece of furniture, made for the marriage of Francis Hurt Sitwell in 1776 . . . [and] a silver racing cup won by an ancestor at the Chesterfield races in 1747.4

Sitwell Sitwell and Frances Hurt Sitwell, collectors of the tapestry and sideboard, respectively, are depicted in Copley’s 1786 composition. The racing trophy of 1747 is also period appropriate; it likely has some now-forgotten connection to the Sitwell children of 1786.

From Copley to Sargent, then, we witness the replicated features of two nuclear families, captured three generations and 113 years apart.5 Taken together, the pendant’s interlocking pieces simulate one uninterrupted line of descent. This ostensibly facile schematic of family lineage has led to oversimplified readings of the Sitwell group portraits as uncomplicated emblems of succession. While Copley scholars and Sargent experts have each analyzed the works independently, the following essay merges these analyses, bringing them together to understand the group pictures as a single pictorial project that aimed to remake the present in the guise of the past.6 Though these people never met, the pendant’s medium attempts to collapse two separate moments—namely, 1786 and 1900—fusing these generations through the mirroring of their representational forms. As one example of the ways in which the genre of portraiture engages with the question of temporality, the Sitwell pendant allows us to consider how and why art can collapse time by evoking the qualities of simultaneity and timelessness.

§

Derived from the Latin pendere, meaning to hang or suspend, the term “pendant” in the year 1900 connoted structures of ornamentation: decorative elements that were, as a rule, oriented spatially. In the case of the Sitwell pendant—matching images divided by time but connected through their common representational genesis—the medium of the pendant highlights difference while insisting on connection.7 I call this specific variety a “cross-generational” pendant. The form acts, through visual representation, as a fulcrum connecting the two generations it depicts. Considered in this way, the cross-generational pendant is a conceptual medium. It utilizes spatial division and the delimitations of the frame as sources of meaning: separate compositions are understood to be divided by time, action, or location. A pendant thus performs its commentary by producing meaning from the space between frames; its paired formula allows the viewer to derive meaning from the juxtaposition of two similar but divergent images. That interval is by no means a dead space; quite the opposite, in fact: the space between frames acts as a kind of conceptual hinge connecting the two works. Like Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony beginning with silence or Robert Rauschenberg’s White Paintings made exclusively with white paint, the blank space that divides a pendant pair is active, a contributing element that changes the relationship between the two discrete objects.8 As Wendy Ikemoto summarizes, “Pendants are paintings about the very relationship between themselves—about their own interpictoriality.”9

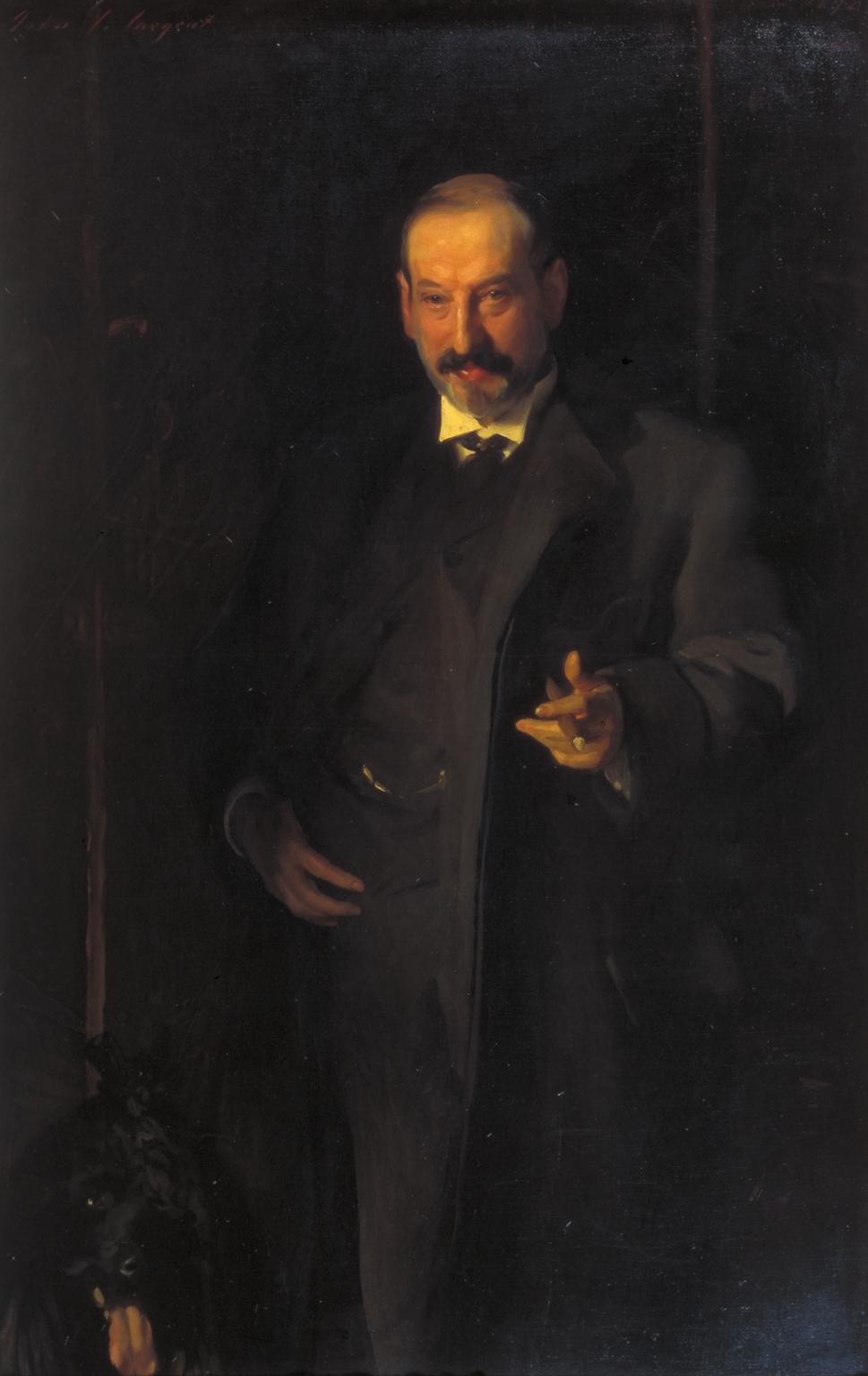

In her scholarship, Ikemoto identifies the pendant’s rise in popularity during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, tracking the medium as the paired images increasingly highlighted contrasts between the connected compositions.10 In a typical example by Sargent, completed only a year before the Sitwell commission, the portrait of Asher Wertheimer appears as the foil to that of his wife, Flora (1898; figs. 3 and 4). He is dressed in black and wrapped in the darkness of a shadowed room. These Cimmerian hues emphasize his illuminated head, cocked forward, and his cigar-holding hand, extended out toward the viewer in trompe l’oeil realism. The effect is punchy and forceful. His wife’s portrait, designed to hang alongside his, is made softer by comparison. Ivory-colored silk and frothy lace are quite literally the white to Asher’s black. Flora’s hand cups a pooled strand of pearls, forming a hollow—a receptive inversion of her husband’s pointed and subtly phallic cigar.

These portraits function both separately (they are currently owned by museums on different continents) and together. They can carry out their representational work alone, but together their paired forms reflect the structural realities of matrimony, emphasizing the conceptual act of joining two individual human beings into a single unit. Concerning the relationship between two opposing ideas or concepts, pendants are also broadly expressive of a relational and comparative mode of thinking about the past that was predominant in fin de siècle England and America. While the Wertheimer pendant demonstrates Sargent’s engagement with the typical expression of this paired form, it also underscores the novelty of the cross-generational Sitwell pendants, which feature a new—and newly deliberate—use of the pendant’s ability to connect people across historical time periods.Sargent’s painting of the Sitwell family and its status as a belated double to Copley’s 1786 work acts as a barometer marking the era’s preoccupation with the representation of time. As the historian Stephen Kern argues in his authoritative The Culture of Time and Space, the period between about 1880 and the outbreak of World War I was marked by profound changes in the way Europeans and Americans perceived time and space. These shifts occurred with the introduction of new technologies and inventions: the telephone, wireless telegraph, X-ray, cinema, bicycle, automobile, and airplane laid the groundwork for this recalibration. They led, in turn, to new cultural developments: the stream-of-consciousness novel, psychoanalysis, Cubism, and the theory of relativity. With the adoption of World Standard Time (by 1884) and the ability for instantaneous communication via telephone, simultaneity was facilitated and actively mediated through technology. As a result, the perception of time and memory was transfigured.11

Henri Bergson’s paradigm-shifting philosophical treatise Time and Free Will, published in 1889, reflects these changes in consciousness. Bergson’s text identifies a period confusion between time as it was experienced in human consciousness and what he terms “artificial” or “abstract” time. Artificial time, for Bergson, is made measurable through the systems of mathematics, physics, and even language.12 These abstract systems made time necessarily linear—and thus rational. In contrast, Bergson’s theory of la durée (duration) explained the cognitive experience of time as simultaneous rather than linear. In other words, Bergson established a new way of thinking about the position of the past by arguing that history and memory coexisted with the present in human consciousness. Bergson’s theory of time as fundamentally dualistic was vastly influential in the century that followed. This “dilemma of discontinuity and continuity,” as Mary Ann Doane argues, became “the epistemological conundrum that structure[d] the debates about the representability of time at the turn of the century.”13

In England, the upper class and members of the British gentry were the most outspoken champions of history and its value in the present. But critics like Friedrich Nietzsche instead warned against a “malignant historical fever” that he said would hinder the impulse for action, create cynicism about the possibility of change, and paralyze the energies of art. Nietzsche’s 1874 essay “The Use and Abuse of History for Life” deemed excessive nostalgia to be a kind of fever or plague parroted by “conservatives,” of which Sir George Sitwell was one.14 In the face of a rapidly changing world, Sir George and others like him developed a keen sense for the historical past as a wellspring of identity and meaning. Clutching at the threads of their deteriorating social control, members of an increasingly obsolete British class system commissioned pictures that would bolster their worth by gesturing to the importance of their own family history. Hence Sargent’s work borrowed from Copley’s in order to disseminate distinct ideas about familial perpetuity and the cultural power of history, assuaging fears about a rapidly changing present.

The Sitwells’ anxiety about their own cultural dominance is legible in Sargent’s group portrait of the family. Whereas Copley’s jocular group is boisterous and buzzy, emphasized by the lunging and angled figures, Sargent’s reflects a deliberate assertion of power articulated through the family’s staunchly upright forms. And unlike the way the children’s attention rests within the frame of Copley’s picture, attention is generally directed outward in the Sargent. In these direct gazes there exists a sense of piercing deliberation about the future. Even the games the children play reflect these differences: in the lighthearted Copley, the house of cards is suspended in the moment of collapse; in the severe Sargent, the two young boys glance up from a serious strategy-based board game.

Key elements of the domestic setting also advance this juxtaposition between the families. The large open window in the Copley lends the painting a picturesque prospect. By 1900, that openness has been closed off in Sargent’s shadowed room, his family group backed instead by a woven tapestry featuring the figure of a woman. A descendant recalled of the figure in the weaving: “Her cold face was reflected in the mirror she was holding before her, with one foot poised above a basket full of enameled masks.”15 This rather ominous imagery calls attention to the performative nature of the painting. By looking out at the viewer, who is understood to be present at some future date, each figure performs the painting’s own futurity.

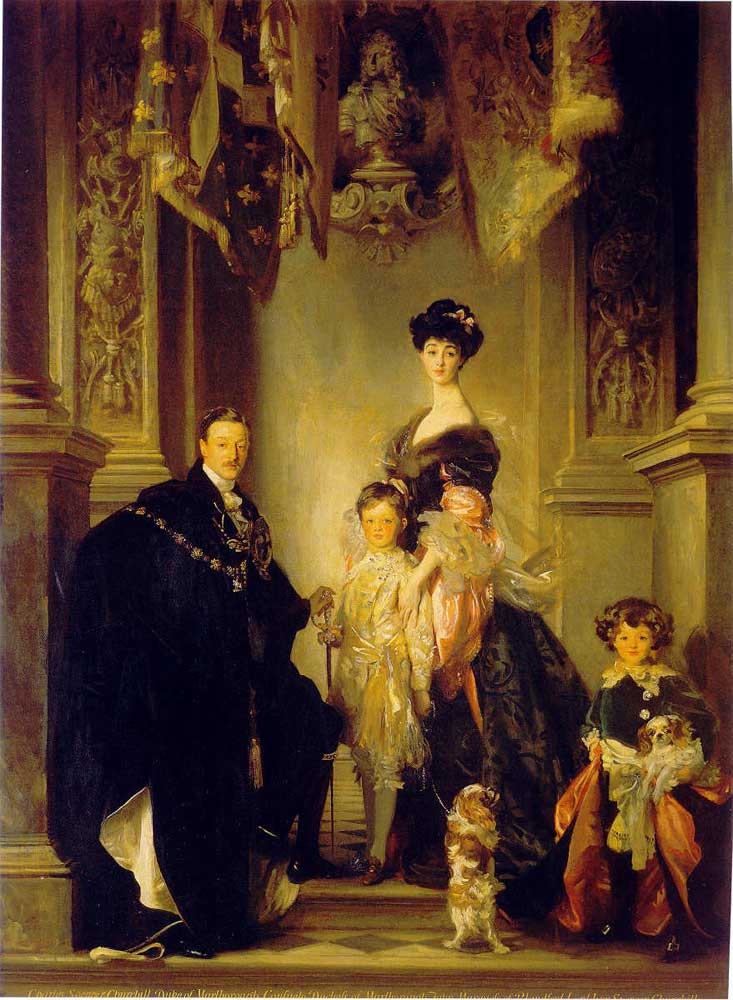

The pendant’s perceived success within its cultural moment inspired others. Five years after completing the Sitwell group portrait, Sargent was commissioned to fashion another cross-generational pendant, this time of the Marlboroughs. The family was an icon of the British gentry and the stewards of sprawling Blenheim Palace in Oxfordshire—the most opulent private residence in Britain. In her autobiography, the former Duchess Marlborough, Consuelo Vanderbilt, recalls the commission of the painting. Sargent was tasked to make “a pendant” for Joshua Reynolds’s (1723–1792) family group of 1777–78 (figs. 5 and 6).16 The paintings were to be installed in the Red Drawing Room at Blenheim, facing each other across the long span of the room, divided by a fireplace and some nine other family portraits by Anthony van Dyck, Peter Lely, and others.

Separated by 130 years and four generations, the nearly eleven-foot-tall Marlborough group portraits were made to match by means of their paired figural organizations, palettes, and settings. Both groups are headed by the mother figure. Her form rises above all others, the peak of a flat pyramid of bodies. Children and dogs and husbands are arranged below her, cast in the role of supporting actors. The palettes of the two pictures are also paired, as are their grandiose architectural settings. In the bottom foreground abutting the frame’s edge, both Reynolds and Sargent painted trompe l’oeil stairs and raised daises. To the left and right of the family groups, columns frame the figures, anchoring them firmly into place. These architectural illusions give the viewer the impression of looking up at the represented figures, who dominate their ordered environments, heightening their implied sense of power, might, and importance. By creating this pendant for Reynolds’s eighteenth-century picture, Sargent deliberately created a kind of modern mirror, folding together 1905 with 1778.The cross-generational pendants of the Sitwells and Marlboroughs reveal Sargent in a role that scholars have not yet identified: as a painter who was contributing to ongoing conversations about the representability of time at the turn of the century. Each pair in its own way evidences the time-defying aims of art by blending, overlaying, and juxtaposing multiple temporal moments, building up a simultaneity of past and present. When he finished the Sitwell group, Sargent commissioned a craftsperson to replicate Copley’s original frame. He presented this facsimile to the Sitwells as a gift, allowing the two pictures to be presented within identical frames.17 In this case, then, it is not only the space between frames that acts as a conceptual hinge connecting the two works. The frames themselves are also physical and even sculptural indications of the paired action happening within the scenes they border.

By playing with the relationality and representability of temporal spheres and their articulation via the medium of portraiture, Sargent engaged with ideas circulating in contemporary literature. In a telling scene from Edith Wharton’s 1905 novel The House of Mirth, for example, the beautiful socialite Lily Bart participates in a lavish high-society entertainment: the tableau vivant. This popular dinner-party trick involved impersonators costumed like living representations of famous Old Master paintings in staged performances. While enacting an eighteenth-century portrait by Reynolds, the heroine is said to have “stepped, not out of, but into, Reynolds’s canvas, banishing the phantom of his dead beauty by the beams of her living grace.”18 Wharton’s imagistic play probes the boundaries between living bodies and their representations. As such, the tableau vivant forms an overt analogy for the concept of “living” history during the Gilded Age by exploring the interfolding of past and present.

Wharton’s tableau vivant echoes some related thematic preoccupations found in Oscar Wilde’s novel The Picture of Dorian Gray, first published in its entirety in 1891.19 The novel’s plot depends on the belief that a portrait is able to capture its sitter’s essential character at the moment of its creation, freezing the model’s form and character outside of time, as if suspended in amber. But Wilde alters this norm in a fantastical twist, since the portrait in Dorian Gray is a magical one, brought to life by Dorian’s own heartfelt prayer for eternal youth. The tragedy that follows reflects the late Victorian interest in the duality of the human psyche. Through the metaphor of the portrait, Dorian’s crimes and cruelties are marked over the years not by wrinkles on his own face or the disfiguration of his own form but by the supernatural portrait:

Often, on returning home [Dorian] would creep upstairs to the locked room, open the door . . . and stand, with a mirror, in front of the portrait that Basil Hallward had painted of him, looking now at the evil and aging face on the canvas, and now at the fair young face that laughed back at him from the polished glass. The very sharpness of the contrast used to quicken his sense of pleasure.20

Wilde’s magical portrait reverses the standard relationship between sitter and portrait: it is the painted canvas that ages and decays rather than the living body of the sitter. Over the course of the story, Dorian grows to feel “keenly the terrible pleasure of a double life.”21 Wilde’s portrait is a literary device that visualizes human duality and personifies the darker half of the novel’s title character. It also describes the portrait’s believed ability to fold together disparate temporal moments: the present moment of viewing the picture with the past moment of its creation.

Fundamental to observational painting is the understanding that time is suspended in the image. But portraits do more still: they superimpose past, present, and future by layering together the acts of sitting for the picture, looking at the picture, and gazing out at future audiences—merging the points of view of the sitter, the viewer, and the captured image. They defy time by freezing the moment of sitting into a singular and distinct record of encounter that may go forward into the future, where it will function as a vehicle expressing the timeless dimension of our human experience that exists beneath the chronological passing of days, seasons, and years.

Portraiture has always been a medium that merges multiple times, intended for future audiences but born of moments shared by sitter and portraitist. As such we might claim that portraits aim to bridge time. In W. J. T. Mitchell’s terms, this effect is anchored in the energies of the art object. He writes, “The picture wants to hold, to arrest, to mummify an image in silence and slow time,” which is true of most any portrait. Sargent’s and Copley’s portraits use mimetic force to preserve bodies and things in an impulse related to the time capsule. But, Mitchell continues, “once [the picture] has achieved its desire, however, it is driven to move, to speak, to dissolve, to repeat itself.”22 This activation of the portrait is evident in the Copley-Sargent pendant, which doubles representation and in doing so connects people across temporal bounds.

§

Edith Sitwell (1887–1964) was the eldest of the three Sitwell children depicted in Sargent’s 1900 portrait of the Sitwell family. She was thirteen when the artist painted her wearing a cherry-red dress and an imperious expression. In her memoir, written decades later, Edith recounts her father’s motivations for the commission. Sir George’s orders for the picture were, according to Edith, as terse as they were clear: Sargent’s composition was to be “a pendant, a Doppelgänger, of the family portrait by Copley that hangs in the dining-room at Renishaw.”23

Perhaps in describing the matching Sitwell pictures as doppelgängers, Edith Sitwell’s comment was sardonic. In the painting, her father, clad in gentlemanly riding gear despite the fact that he never rode, wished to appear as the belated twin to his great-grandfather.24 But in applying the term “doppelgänger,” Edith made a deeper connection between the paintings and their subjects. Positioning the two compositions within a slippery temporal scale, she observed something uncanny about the twinned paintings and their efforts to link the people they depict across the time separating them. Like the doppelgängers found in Wharton’s and Wilde’s literary examples, Sir George’s project of remaking Copley’s family picture was a statement about the longevity of the portrait and its powers of connection.

In 1945, Edith Sitwell would continue the family tradition by posing with her brother Osbert beneath Sargent’s painting (fig. 7). Taken by the German-born photographer Bill Brandt (1904–1983), who was known for his anthropologically driven examinations of the British class system, the image shows the stoic siblings—now grown old—posed in the Renishaw drawing room below their childhood portrait. With their shadows cast back upon Sargent’s painting, they stare directly out at the camera. The arrangement feels both facetious and sincere, a self-aware quotation of a quotation. Behind Edith and Osbert sits the inlaid commode designed by Robert Adam that is included prominently in Sargent’s composition. In Brandt’s photograph, our perspective on this object and the sitters themselves constitutes a kind of temporal doubling, offering a simultaneous view of the represented and the representation. In this way, Brandt’s photograph captures a moment when objects and bodies are actively re-encoded in the service of familial identity and its perpetuity in the future. Like Copley’s and Sargent’s pendant portraits, Brandt’s group portrait links disparate moments in time to create a fiction of simultaneity and the impression of timelessness—a temporal sphere unique to the portrait medium.

Cite this article: Caroline Culp, “Pendant Across Time: John Singleton Copley and John Singer Sargent,” in “About Time: Temporality in American Art and Visual Culture,” In the Round, ed. Hélène Valance and Tatsiana Zhurauliova, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 8, no. 2 (Fall 2022), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.14973.

Notes

- Osbert Sitwell, Left Hand, Right Hand! (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1944), 255. ↵

- Guest Editors’ note: This image is not illustrated here because the owners of the painting have not consented to its publication in this article and have declined to provide a high-resolution image. The artwork is in the public domain, and as per case law (Bridgman Art Library v. Corel Corp., 1999), faithful reproductions of two-dimensional works of art are not copyrightable; nevertheless, a decision has been made to respect the wishes of the owner, whose representative wrote: “The key principle of maintaining the integrity of the Copley painting as part of a private collection is the foundation on which this decision has been made. The act of agreeing to the use of the Copley image in a free open-access online publication would contradict and jeopardise fulfilling this objective.” ↵

- Desmond Seward, Renishaw Hall: The Story of the Sitwells (London: Elliott & Thompson, 2015), 106; 255n3. Regarding Sargent’s group portrait, correspondence reveals that “it was the painter who insisted on {the} clothes, not his patron” (106). ↵

- Sitwell, Left Hand, Right Hand, 257–60. Osbert Sitwell recalls that Sargent came to Renishaw “to make the acquaintance of his sitters and to see the Copley group, with which his picture was to tally, for it was to be of the same size, the figures in it of the same proportion, and, in so far as he could be induced to make it, of a similar feeling.” He further remembers that “the Copley immediately excited Sargent’s admiration, and his first words, on seeing it, were, ‘I can never equal that’” (258). ↵

- Sitwell Sitwell, depicted in the Copley, was the First Baronet of Renishaw; Sir George Reresby Sitwell, Fourth Baronet, was his great-grandson. ↵

- For scholarship discussing the Copley-Sargent pendant, see Elaine Kilmurray, Richard Ormond and Mary Crawford Volk, eds., John Singer Sargent (London: Tate Gallery, 1998), 156–57; Richard Ormond, Sargent: Complete Paintings (New Haven, CT: Published for the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art by Yale University Press, 1998), 3:45–46; Emily Ballew Neff, John Singleton Copley in England (London: Merrell Holberton, 1995), 55–57. ↵

- As Christine Beevers, archivist at Renishaw Hall, relayed to me: “So as far as we know the two paintings have never hung together.” In estate inventories of 1895 and 1922 and in an October 1938 Country Life feature, the Copley is listed as hanging in the dining room. Before 1906, the Sargent hung in the ballroom before it was moved to the drawing room, where it has been at least since the 1922 estate inventory. Christine Beevers, email correspondence with the author, March 2020. ↵

- In a 1999 interview, Rauschenberg said of his White Paintings: “I called them clocks. If one were sensitive enough that you could read it, you would know how many people were in the room, what time it was, and what the weather was like outside.” Robert Rauschenberg, interview by Walter Hopps and David A. Ross, “Robert Rauschenberg discusses White Painting {three panel}, at SFMOMA, May 6, 1999,” SFMOMA, https://www.sfmoma.org/research-materials/whit_98-308_005. ↵

- Wendy N. E. Ikemoto, Antebellum American Pendant Paintings: New Ways of Looking (London: Routledge, 2018), 3. ↵

- Ikemoto, Antebellum American Pendant Paintings, 18. A good example is J. M. W. Turner, Peace—Burial at Sea and War—The Exile and the Rock Limpet (c. 1842). ↵

- Stephen Kern, The Culture of Time and Space, 1880–1918 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1983), 1. ↵

- Henri Bergson, Time and Free Will: An Essay on the Immediate Data of Consciousness, trans. R. L. Pogson (London: George Allen & Unwin, 1910), xi. ↵

- Mary Ann Doane, The Emergence of Cinematic Time: Modernity, Contingency, the Archive (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2002), 9. As Doane observes, “The intense debates around continuity and discontinuity at the turn of the century, which support and inform discussions of the representability of time, are a symptom of the ideological stress accompanying rationalization and abstraction.” ↵

- Friedrich Nietzsche, The Use and Abuse of History, trans. Adrian Collins (New York: The Bobbs-Merrill Company, 1957), 4. ↵

- Sitwell, Left Hand, Right Hand, 245. ↵

- Bruce Redford, John Singer Sargent and the Art of Allusion (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2016), 121. ↵

- Ormond, Sargent, 3:45. ↵

- Edith Wharton, The House of Mirth (London: Wordsworth, 2002), 119. See also Walter Benn Michaels, The Gold Standard and the Logic of Naturalism: American Literature at the Turn of the Century (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1987), 239. ↵

- Sargent knew Wilde—they both had homes on Tite Street in Chelsea, a bohemian borough favored by painters, poets, and radicals at the end of the nineteenth century. Sargent settled in London in 1886 and moved into a studio at 31 Tite Street, a space recently vacated by James Abbott McNeill Whistler. Sargent would maintain this studio until his death in 1925. ↵

- Oscar Wilde, The Picture of Dorian Gray (London: Penguin, 2003), 124. ↵

- Wilde, The Picture of Dorian Gray, 167. ↵

- W. J. T. Mitchell, What Do Pictures Want?: The Lives and Loves of Images (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005), 72. ↵

- Edith Sitwell, Taken Care of: The Autobiography of Edith Sitwell (New York: Atheneum, 1965), 48–49. Edith Sitwell was a successful poet, notable for her poems’ striking imagery. ↵

- In her autobiography, Edith Sitwell remembers, “My father was portrayed in riding-dress (he never rode).” Sitwell, Taken Care of, 48–49. ↵

About the Author(s): Caroline Culp is an Adjunct Assistant Professor in the Art Department at Vassar College.