Waiting for Mlle Bourgeoise Noire and the Power of Interruption

PDF: Segebre Salazar, Waiting for Mlle Bourgeoise Noire

“All these years she has been waiting,” wrote Lorraine O’Grady (b. 1934) in 1981, “for this 25th Anniversary to give her subjects her final conclusion.”1 She was referring to the quarter century between her graduation from the all-women, elite institution, Wellesley College, and the debut of her artistic persona as Mademoiselle Bourgeoise Noire (French for Miss Black Middle Class). Under this guise, O’Grady orchestrated a series of performative interventions in New York City in the early 1980s. She protested two art openings dressed like a pageant winner in a floor-length gown made out of 360 white leather gloves. Carrying a bouquet of flowers, she asked attendants, “Won’t you lighten my load?” (fig. 1). After handing out every flower, O’Grady pulled out what she termed “the whip-that-made-plantations-move” and self-flagellated repeatedly.2 Eventually throwing the whip down to the floor while still panting, she screamed a poem. For the opening of an exhibition at the New Museum about the use of artistic alter egos, titled Persona (1981), which featured only white artists, her poem spoke about waiting in protest:

WAIT

wait in your alternate/alternate spaces spitted on fish hooks of hope

be polite wait to be discovered

be proud be independent

tongues cauterized at

openings no one attends

stay in your place

after all, art is

only for art’s sake

THAT’S ENOUGH don’t you know sleeping beauty needs

more than a kiss to awake

now is the time for an INVASION!3

With these verses, Mlle Bourgeoise Noire (hereafter MBN) described waiting as an imposition forced onto some subjects more than others. Non-white artists are left waiting “to be discovered.” MBN had been waiting for her moment to protest racism and oppression by disrupting bourgeoise codes of feminine propriety. Instead of passively waiting for change, she intervened and called for action.

Although best known for interrupting exhibition openings, the project titled Mlle Bourgeoise Noire (1980–83) also included The Black and White Show (1983), an exhibition featuring fourteen Black and fourteen white artists, and a participative performance, Art is . . . (1983), in which parade participants were photographed behind a golden frame.4 These interventions counteracted oppression: they directly altered the racial politics of exhibition and art making, positively changing the status quo. This essay, however, focuses on MBN’s interruptions of openings, which confronted viewers with a vehemently negative image of the status quo. According to the artist, MBN was “shouting out what the situation was.”5 And the situation was particularly dire. Yet, the confrontational “shouting out,” unlike later interventions, suggests that artistic militancy effects important changes indirectly and negatively through temporality.

MBN herself was confronted with critical and curatorial silence. Her performance took on the imbrication of race, class, and gender at a time when there was little awareness of intersectional critique. Zoé Whitley rightly notes that the first recorded usage of the term “intersectionality” would not come until 1989.6 MBN has been excluded “from most scholarly accounts of institutional critique” and precedes, for instance, the Guerrilla Girls by five years and Fred Wilson’s Mining the Museum by more than a decade.7 In Speaking Out of Turn (2021), the compelling, sole monograph on the artist, Stephanie Sparling Williams locates the performances’ radicality in their “direct-address deployment of an alien body and alienation.”8 For her, the intervention’s political implications reside in the physical act of a Black and female body speaking directly, without prompts or invitation, in an exhibition space. Although I agree that the performance does intervene in the historical negation of Black female sexuality, MBN cannot be exclusively understood as a critique of representation in spatial terms. This would overemphasize her body in the room and neglect O’Grady’s interjection into the politics of time.

Sparling Williams hints at this temporal dimension of the piece when she qualifies O’Grady’s “visual modes of address” as “unexpected and possibly invasive (out of turn).”9 MBN was not expected, and the piece’s power lies in the interruption of expectations, which have temporal registers. Even how O’Grady introduced her “alien” Black body into the museum, both sexualized and estranged in her guise as an aging pageant contestant, challenges expectations. Conceived when the artist was forty-five years old, her contrasting use of a youthful debutante’s persona assaults the imperative of youth regulating the appearance of bodies gendered female in public space. Here MBN worked against social conventions, which are a form of expectation similar to how racist stereotypes function and condition what is expected from certain bodies. I endorse Whitley’s concluding observation that O’Grady “made a virtue of defying expectations,” and I wish to explore the performances’ temporality as a form of waiting—because when we expect something, we are waiting for it.10

MBN subverted the expectation of an opening as a cordial moment of celebration that adheres to social codes and scripts. Unannounced, uninvited, and in costume, MBN stalled and interrupted the opening’s progression, thwarting expectations. Such ruptured expectations made audience members wait. I locate the performance’s most incisive protest, as well as its most hopeful and enduring gesture, in the highly situated experience of waiting that MBN forced on her unsuspecting spectators. I will discuss below how I interpret this waiting through the image of Frantz Fanon waiting for racist representations of himself in a movie theater, which further imbricates waiting with expectation and the politics of spectatorship. MBN’s performances did shout out the situation, but in a style that interrupts how time affects us psychosocially—some of us more than others. Through O’Grady’s work, waiting becomes a metaphor for how power subjugates and temporizes.

Temporality and Power

Waiting encompasses the time transpiring until an expected arrival or departure, or the interval before an event’s beginning and ending, among many other situations. Time often feels slow and boring while waiting. The word also describes time as service, performed by waiters, waitresses, and so-called ladies-in-waiting, who assist royalty. To this effect, Lydia Goehr writes, “There is of course no one thing meant by waiting. . . . The very idea of waiting prompts many thoughts (as it is meant to): of the relation of theory to action, of servitudes and freedoms.”11

This in-between temporality is rarely desired—not only because of the possible discomfort of waiting but also due to its political implications, as is particularly evident in histories of liberation and decolonial struggle. The refusal to wait, for example, during the US Civil Rights Movement is what Theodore Martin describes as “the unwillingness to abide the repeatedly delayed timeline of so-called progress.”12 In a similar vein, Martin Luther King Jr.’s 1964 manifesto against racial segregation is titled Why We Can’t Wait. Audre Lorde echoes Dr. King’s call to nonviolent action in a speech commemorating Malcolm X in 1982:

There is no black person here who can afford to wait to be led into positive action for survival. . . . For while we wait for another Malcolm, another Martin, another charismatic Black leader to validate our struggles, old Black people are freezing to death in tenements, Black children are being brutalized and slaughtered in the streets. . . . And if we wait to put our future into the hands of some new messiah, what will happen when those leaders are shot?13

Waiting is therefore diametrically opposed to Black life: the longer we wait, the more Black lives will be lost. Lorde’s rhetoric against waiting resembles the figure of speech “It’s about time,” a way of saying that something should have already happened. Lorde argues against political passivity and calls for change. In the early 1980s, O’Grady shared Lorde’s intent.

MBN’s first intervention functioned as a confrontation and a daring—a call to action tantamount to Lorde’s rhetoric on waiting. She interrupted the inaugural show at Just Above Midtown (JAM)’s new location. According to O’Grady, the “occasional poem” ought to denounce “timid” Black artists in the context of one of the only Black-owned galleries at the time. This was her reaction to Afro-American Abstraction (1980), which O’Grady described as a “well groomed” exhibition: “it was art with white gloves on.”14 The performance concluded with MBN screaming, “That’s enough. . . . No more boot-licking, / No more ass-kissing. . . . / BLACK ART MUST TAKE MORE RISKS!!!” which can be interpreted as a critique on assimilation.15 Her “That’s enough,” which recurs in her New Museum poem, insists on a disruption of what Black art is allowed to mean and look like. These verses reproduce, to an extent, the prejudice that abstract art is apolitical, associated with whiteness, and therefore incompatible with any “cure for the invisibility imposed by systemic racism.”16 Yet O’Grady’s critiques of assimilation, both abstract and figurative, taking issue with the conditions under which Black art is allowed visibility.

The aforementioned use of gloves for the dress made for these disruptive performances similarly targets a dynamic of assimilation, namely internalization. For O’Grady, the gloves stand for internalized oppression while the whip stands for externalized oppression.17 In a museum context, white gloves also connote the curators’ and conservators’ caring for the art, indexing institutional gatekeeping. For art to have white gloves on means that it is too polite, too domesticated, too bourgeois. O’Grady critiques the art world as an extension of bourgeois society, drawing attention to the glove-wearing hands both behind and in front of the work. She thereby strips the museum of its supposed universal neutrality. Interpreting this gesture further, the white gloves, symbolizing internalized oppression, also signify the latent desire to identify with normative society. It was important for her that the gloves were second-hand, used and therefore “believed-in” by women.18 She herself owned a pair of white leather gloves from her years at Wellesley, which, in part, inspired the gown.19

Such contradictions lie at the heart of Fanonian thought. The afterlife of colonialism is for Fanon both inside and outside its subjects. The way we look and the way we are looked at condition not only our role in society but also our psychic life. Even in moments of apparent solitude, a colonial subject has the racist other as interlocutor. This dynamic between colonial gaze and the colonized’s subjective identification reverberates through MBN’s critique of exclusion and segregation, particularly by the ways in which artists of color are “kept in place” through a rhetorical deployment of time; that is, by being told to wait their turn. Waiting is a way to keep people in positions of subservience through hope and duration. The treachery of looking at oneself through the eyes of the racist dominant order is fundamental to keeping racially marked subjects in place, always waiting for their time and hoping for recognition and reparation—a cruel logic that O’Grady momentarily subverted in her performances.

In the poem recited at the New Museum, MBN’s mission is clear: No more waiting but, instead, “INVASION!” While the last verse brims with temporal urgency, the verses preceding it function rhetorically. When MBN shouted, “WAIT / wait in your alternate/alternate spaces spitted on fish hooks of hope / be polite wait to be discovered,” she was not necessarily demanding these things but instead rhetorically prompting audience members to wait and stay put, thus building up an opposition to the poem’s punchline.20 This reading, nonetheless, privileges the artist’s intention and assumes previous knowledge of the end, which her audience would not have had that night. Moreover, Judith Wilson considers the poem “a scathing denunciation of Black artists’ political passivity in the face of curatorial and critical apartheid.”21 Resonating with Lorde’s earlier remarks, Wilson suggests we are passively complicit when we wait. Yet, the first stanza of the poem includes a second register: waiting is not only what MBN is tired of hearing but also what she imposes on the audience. “WAIT” also functions in the poem as a rhetorical figure to keep subjects in place, like saying, “Your day will come, just wait for it.” MBN is “returning” the imposition to wait vengefully, spitting it back as false consolation. In both registers, waiting expresses power relations—there are those who wait and those who make others wait.

This is an important understanding of how power and domination transpire through the time of waiting. Pierre Bourdieu writes, “Waiting is one of the privileged ways of experiencing the effect of power. . . . Waiting implies submission. . . . The art of taking one’s time . . . of making people wait, of delaying without destroying hope, of adjourning without totally disappointing . . . is an integral part of the exercise of power.”22 Bourdieu’s problematization of waiting as the intersection of power and temporality could give the false impression that it only affects the subjugated. As privileged individuals, we do not only let others wait for and on us, but we also wait ourselves. This renders “What are we waiting for?” an important question. The object of the wait influences and often overdetermines the waiting. There is, for example, an important difference (risking redundancy) between waiting for your delayed five-course meal or a delayed visa, between waiting for the bus or medical test results. What we are waiting for conditions so much of the wait. The object of the wait MBN refuses and criticizes is twofold. It is waiting for (sociopolitical) representation as well as for the end of racist segregation. The poem conveys an understanding of waiting as a cruel form of oppression—cruel because it rhetorically delays without adjourning; it stretches hope and asks for patience without announcing an end. It is telling that MBN follows waiting with an image of those who wait “spitted on fish hooks of hope.”

Such a reading again risks privileging a form of textual analysis that was unavailable to almost all original spectators. For them it was, first and foremost, an exhibition opening, a seemingly apolitical bourgeois event that was suddenly politicized through MBN’s interruption. And interruptions make people wait, usually for the interruption’s adjournment and with it a return to “normal.” Her presence alone already interrupted the opening. Moreover, when she shouted, “WAIT,” she was not literally asking listeners to wait but instead interrupting, asking for their attention—no different from uttering the imperative in the middle of a conversation to interrupt an interlocutor. The interruption itself marks the first instance of protest—not allowing an event to unfold according to expected bourgeois propriety.

For her second intervention, MBN arrived once again wearing a tiara and the custom-made dress sewn out of 360 white gloves. She moved through the opening smiling and handing out flowers. Once she ran out of flowers, a whipping contraption hidden under the chrysanthemums appeared. After switching into longer gloves, she whipped herself more than one hundred times. MBN eventually stopped, dropped the whip, and declaimed the poem. At first, MBN was the one waiting on the audience, servicing them, handing out flowers, smiling like a debutante. By the time the whipping ended, the roles had reversed. Those watching the performance for the first time must have been surprised or somewhat forced to realign their expectations as the performance turned into a violent and vociferous act of protest, as the audience’s distraught expressions, caught in a photograph, suggest (fig. 2). O’Grady remembers whipping herself for what must have been five to ten very long minutes.23 A number of spectators were likely waiting for the self-flagellation to end—waiting for opening night to go on as planned and for the confrontation to be over. The show’s curators, Lynn Gumpert and Ned Rifkin, must have recognized O’Grady and were definitely waiting for the intervention to end; they had decided not to include her in the show and invited her instead to give a children’s workshop as part of the exhibition’s outreach program—an invitation rescinded after MBN’s performance.24

When MBN struck at the New Museum, not only did her performance make the role of waiting explicit, but some spectators were literally waiting for her, expecting her unrequested presence, including some who knew her or had been present for her previous performance at JAM. She repeated all aesthetic decisions of the first intervention—the outfit, the actions, the occasional poem, the gloves, the dramaturgy, the piece’s urgent tone—which suggests some viewers at the New Museum may have recognized her and known what to expect. For instance, the MC, Dr. Edward B. Allen, who accompanied MBN to both openings, was definitely aware, as were the photographers Salima Ali and Coreen Simpson (fig. 2, far right) documenting the performance. They were thus waiting for MBN to deliver her scathing and lyrical critique of the temporal logic sustaining racial segregation. They were in the know and perhaps got what they were waiting for.

The Interval of Waiting

In both performances, after handing out the flowers, MBN paused. She took off her cape, and the MC handed her a longer pair of white leather gloves to put on (fig. 3). This emphasized her symbolic mobilization of the gloves (letting Dr. Allen wait on her) and also marked her transition from the charming greeter to the vociferous and violent Mademoiselle. Just as the poem jumps registers between stanzas, so does the performance’s dramaturgy. The self-flagellation then began. This moment marked the interval between a performance of internalization and one of denunciation: a refusal to continue repressing subjugation. O’Grady considers “the moment when she throws down the whip” as the most important in the performance (fig. 4).25 It must have made the audience feel insecure, confused, and perhaps intrigued. Here was yet another element of waiting, when no one could anticipate what would come next.

This critical scene in the piece can be examined in light of Fanon’s pivotal discussion of waiting in the fifth chapter of Black Skins, White Masks (1952), titled “The Lived Experience of the Black Man.” Fanon writes, “If I were asked for a definition of myself, I would say that I am one who waits.”26 The chapter concludes with an image of Fanon waiting in a movie theater: “I can’t go to the movies without encountering myself. I wait for myself. Just before the film starts, I wait for myself.”27 He refers to his own disenchantment with Hollywood and the experience of seeing himself as an object of the colonial gaze. An interpretation of the passage is that when Fanon waits for himself, he is actually anticipating (and dreading) a racist caricature: “A black bellhop is going to appear. My aching heart makes my head spin.”28 The potential for representation makes him wait for himself, and only the worst is to be expected of cinema, which conditions the wait. Fanonian waiting is inseparable from two other important motifs: the explosion and its untimeliness.

Fanon often refers to an explosion that is both to come and has already happened but one for which it is always too early or too late. In the opening pages of both the book and the chapter, Fanon references an explosion: “Don’t expect to see any explosion today. It’s too early . . . or too late” and “I explode. Here are the fragments . . .”29 The explosion and its untimeliness can be interpreted as a pessimistic reading of liberation or independence movements. No matter when these come, they will be too late or too early. The timing of decolonization will always be off. I interpret Fanon’s waiting for himself—like MBN’s shouting of “THAT’S ENOUGH”—as a waiting for oneself to take action and explode—not to change the world or the status quo but to explode in full knowledge of any action’s futility. The explosion is just one of the links in an ongoing chain of unfolding events and actions contributing to revolution. Much like O’Grady, Fanon identifies the “mediocrity” of the bourgeoisie in former colonies as contributing to the continuity of (neo)colonialism.30 David Marriott rightly interprets Fanon’s waiting as not liberatory and argues that there is a “priority, for Fanon, of waiting or expectation over that of responsibility and action.”31 Even though not outright revolutionary, this ascribes a catalyzing potential to the experience of waiting as a specific form of resistance. Somewhat counterintuitively, what is so interesting about waiting is how it disappears, how it becomes a gateway to other phenomena, a sort of galvanizing spatiotemporal portal. Waiting was a way for MBN to dissent via the denunciation of oppression by externalizing repression and to protest via the temporal disruption of the openings.

Regarding the opposition of action to inaction and passivity to activity, waiting for oneself means also waiting for oneself to explode or even just stand in protest. This interpretation, however, risks oversimplifying the scene. It is not just waiting as a call to action (like an untimely explosion) but also waiting for the foreseeable racism of representation, waiting for Fanon’s “black bellhop [who] is going to appear.”32 Waiting for oneself cannot be separated from this: Fanonian waiting stems from expecting racist representation. In other words, if racism is foreseeable and therefore to be expected, we are not actually waiting for the racist image or event to come but for ourselves. Under this light, waiting for oneself is both a call to action and an interrogation of complicity.

Such self-questioning, like waiting’s cyclicality, is rarely pleasant. I refer here to the too-soon/too-late motif Fanon couples with the explosion of waiting for oneself, which renders history a vicious cycle of waiting and revolt. Writing on Fanon’s waiting scene, Kara Keeling notes, “The black’s explosion shatters the cycle of anticipation only to reinstate it as the interval between that explosion, decolonization and the next one.”33 Our experience of that interval between cycles becomes one of waiting. In a later book, Keeling refers to this interval as the “yet still” temporality of Black experience.34 Black sovereignty is not right now; it must be waited for. Nonetheless, Keeling sees some hope in “the temporality of the interval [because it] is not necessarily that of (neo)colonial reality. Instead, the temporality of the interval in which neo(colonial) existence is stuck is an opening.”35 When MBN put on her gloves and started whipping herself, to the surprise of most of her audience, she inaugurated such an interval, an opening of the opening. When throwing down the whip and shouting, “WAIT,” MBN reinstated another interval of waiting, yet one that opened the waiting for oneself of some spectators, at least of those in the know, to waiting for political representation. Such waiting might seem futile given the aforementioned cyclicality, yet it is also an invitation to wait as a passive form of endurance and resistance.

Enduring the Wait

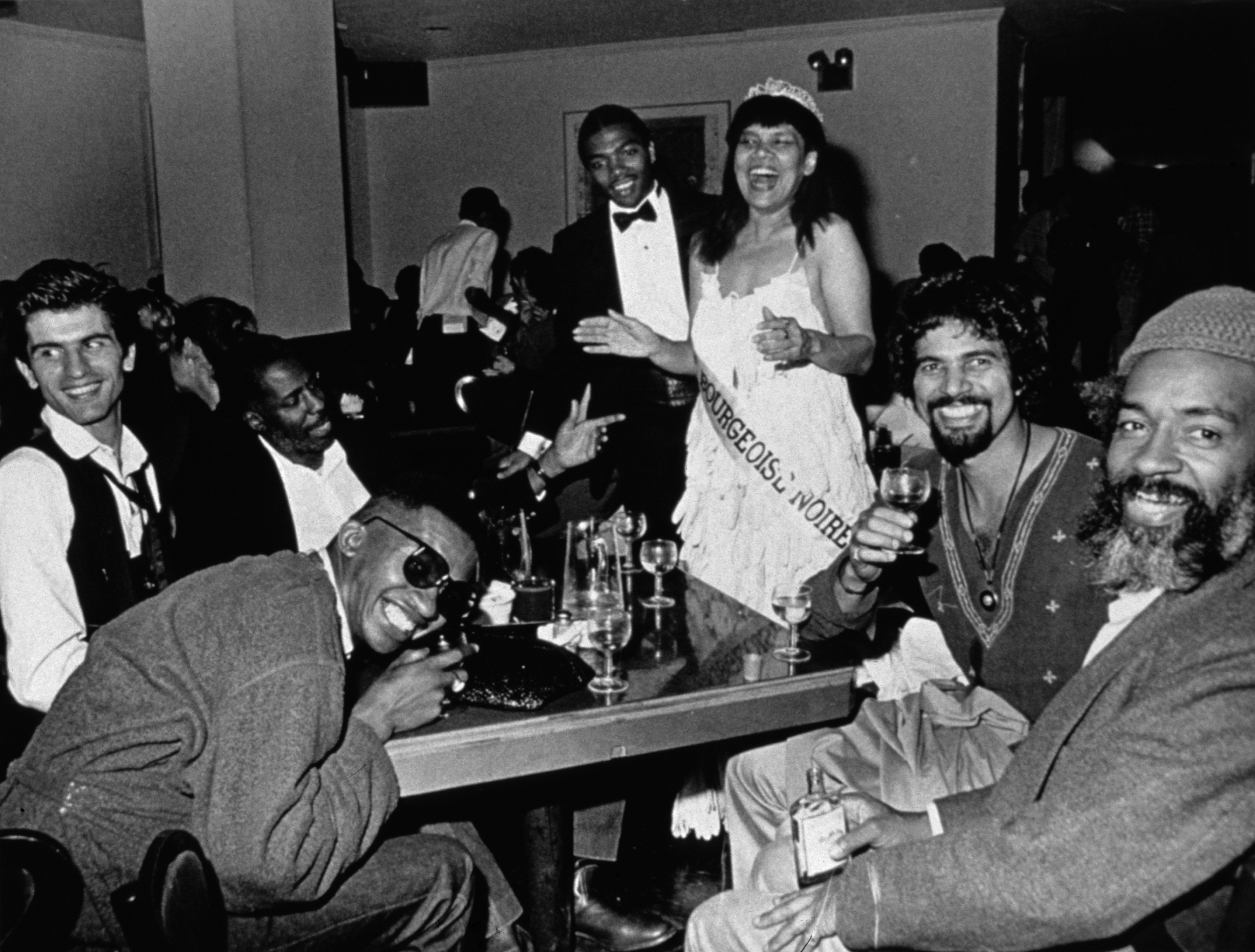

MBN’s interruptions dispelled most expectations on opening night. Interruptions are a strategy to stop time, to break it into intervals and delay its flow. Whenever something is deferred or slowed down, someone will be waiting. From this perspective, MBN’s performance must have seemed to most spectators as a vengeful interruption; however, some did know what to expect. The night at the New Museum was not only about protesting the continuous deferral of Black struggle but also about celebration (fig. 5). A photograph shows O’Grady at a bar after the intervention, laughing with friends and fellow artists, such as Richard DeGussi, David Hammons, George Mingo and Jorge Luis Rodriguez. Aside from its joyous character, the photo confirms that some spectators knew of MBN’s plan through her previous intervention or because they were supportive friends and collaborators. Such spectators were maybe waiting for justice, for the people to get a shock, or for someone to tell it how it is. Those in the know—who knew what they were waiting for, aware of its futility—were, in fact, waiting for themselves. What we wait for can make waiting oppressive inasmuch as it can also offer, perhaps all too fleetingly, an interval in which the vicious cycle that Fanon and Keeling characterize as endless is briefly upheld.

Waiting is an essential category of the aesthetic experience MBN triggered and a political strategy to weaponize time.36 Although waiting is rightly critiqued as oppressive in Black radical thought, and MBN reinforces this notion of waiting as undesired experience, she also sheds light on how its aesthetic transformation is not oppressive. Similarly, Fanonian waiting can be read as an opening in an interval between waves of oppression, which is not the end of (neo)colonialisms but does reconfigure one’s orientation toward time and its politics. Thus constituting waiting for oneself as a passive act of protest helps us endure the present.

Warning against adding another “burden on black female flesh by making it ‘a placeholder for freedom,’” Saidiya Hartman observes that “strategies of endurance and subsistence do not yield easily to the grand narrative of revolution,” insisting that we carve a space for these.37 Waiting for oneself is one such strategy. It helps understand how the confluence of the smiling with the self-flagellating pageant winner, as well as of the bourgeois with the militant artist, enable experiences and practices of resistance. The aesthetics of waiting counterintuitively find hope within passivity and the seemingly unchangeable—one inseparable from MBN enduring twenty-five years of waiting before “giv[ing] her subjects the final conclusion,” which meant giving her spectators different things to wait for.38 And what we wait for can be both an imposition, reinforcing the color line, and an opening to subvert it. Waiting for oneself means remaining militantly hopeful.

Cite this article: José B. Segebre Salazar, “Waiting for Mlle Bourgeoise Noire and the Power of Interruption,” in “About Time: Temporality in American Art and Visual Culture,” In the Round, ed. Hélène Valance and Tatsiana Zhurauliova, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 8, no. 2 (Fall 2022), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.15256.

Notes

My research on the aesthetics of waiting has been possible in part to a Fundación Jumex Arte Contemporaneo scholarship (2020–2023).

- Lorraine O’Grady, “Mlle Bourgeoise Noire 1955” (1981), in Lorraine O’Grady: Writing in Space, 1973–2019, ed. Aruna D’Souza (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2020), 10. ↵

- O’Grady, “Mlle Bourgeoise Noire and Feminism” (2007) in D’Souza, Lorraine O’Grady, 111. ↵

- O’Grady, “Mlle Bourgeoise Noire 1955” (1981), in D’Souza, Lorraine O’Grady, 291n4. ↵

- There is arguably a fifth intervention. In 1982 O’Grady sent questionnaires to thirty-six Black artists inquiring about their perspectives on the art world; few replied, and this intervention waits (archived) for its final conclusion. See Stephanie Sparling Williams, Speaking Out of Turn: Lorraine O’Grady and the Art of Language (Oakland, CA: University of California Press, 2021), 88–90. ↵

- Lorraine O’Grady, “The Mlle Bourgeoise Noire Project, 1980–1983” (2018) in D’Souza, Lorraine O’Grady, 252. ↵

- Zoé Whitley, “Mlle Bourgeoise Noire Throws Down the Whip: Alter Ego as Fierce Critic of Institutions,” in Lorraine O’Grady: Both/And, ed. Catherine Morris and Aruna D’Souza (Brooklyn, NY: Dancing Foxes Press, 2021), 55. ↵

- Whitley, “Mlle Bourgeoise Noire Throws Down the Whip,” 55. Moreover, O’Grady was part of the Guerrilla Girls (Alma Thomas) but disidentified with their politics of anonymity given the historical erasure of Blackness. See Lorraine O’Grady, “Interview with Jarrett Earnest” (2016), in D’Souza, Lorraine O’Grady, 240–42. In the last ten years, her work has gained more recognition through a retrospective at the Brooklyn Museum (2021) and in groundbreaking group exhibitions such as WACK! and the Feminist Revolution (2007, Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles) and We Wanted a Revolution: Black Radical Women, 1965–1985 (2017, Brooklyn Museum). ↵

- Sparling Williams, Speaking Out of Turn, 63. ↵

- Sparling Williams, Speaking Out of Turn, 98. ↵

- Zoé Whitley, “Mlle Bourgeoise Noire Throws Down the Whip,” 57. ↵

- Lydia Goehr, “Painting in Waiting: Prelude to a Critical Philosophy of History and Art,” in Proceedings of the European Society for Aesthetics 11 (2019): 2, https://www.eurosa.org/wp-content/uploads/ESA-Proc-11-2019-GoehrKeynote-2019.pdf. ↵

- Theodore Martin, “On Time,” in About Time: Fashion and Duration, ed. Andrew Bolton with Jan Glier Reeder, Jessica Regan, and Amanda Garfinkel (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2020), xxv. ↵

- Audre Lorde, “Learning from the 60s,” in Sister Outsider (Berkeley, CA: Crossing, 2007), 141. ↵

- O’Grady, “The Mlle Bourgeoise Noire Project, 1980–1983,” 254. See also Linda Montano, “Lorraine O’Grady,” in Performance Artists Talking in the Eighties (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2000), 403. ↵

- O’Grady, “Mlle Bourgeoise Noire 1955,” 10. ↵

- Darby English, 1971: A Year in the Life of Color (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016), 8. For an overview of discussions on abstraction in African American art history and a critique of Darby’s project, see Huey Copeland, “One-Dimensional Abstraction,” Art Journal 78, no. 2 (2019): 116–18, https://doi.org/10.1080/00043249.2019.1626161. ↵

- Montano, “Lorraine O’Grady,” 403. ↵

- Montano, “Lorraine O’Grady,” 404. ↵

- She wore these clipped to her chest in Art Is . . . See O’Grady, “The Mlle Bourgeoise Noire Project, 1980–1983,” 250. ↵

- O’Grady, “Mlle Bourgeoise Noire 1955,” 291n4. ↵

- Judith Wilson, “Lorraine O’Grady: Critical Interventions,” in Lorraine O’Grady: Photomontages (New York: Intar Gallery, 1991), 5. ↵

- Pierre Bordieu, Pascalian Meditations, trans. Richard Nice (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2000): 228. ↵

- O’Grady, “The Mlle Bourgeoise Noire Project, 1980–1983,” in D’Souza, Lorraine O’Grady, 252. ↵

- See Whitley, “Mlle Bourgeoise Noire Throws Down the Whip,” 50. ↵

- O’Grady, “The Mlle Bourgeoise Noire Project, 1980–1983,” 254. ↵

- Frantz Fanon, Black Skins, White Masks, trans. Charles Lam Markmann (London: Grove, 2008), 91. Although the original French reads, “si j’avais à me définir, je dirais que j’attends,” the phrase “j’attends” has also been translated as “in expectation,” further reinforcing the imbrication of waiting and expecting. For the original, see Frantz Fanon, Peau noire, masques blancs (Paris: Éditions du Seuil, 2007), 97. Compare with Black Skins, White Masks, trans. Richard Philcox (New York: Grove, 2008), 99. ↵

- Fanon, Black Skins, White Masks, trans. Philcox, 119. ↵

- Fanon, Black Skins, White Masks, trans. Philcox, 119. ↵

- Fanon, Black Skins, White Masks, trans. Philcox, xi, 89. Ellipses original. ↵

- See Frantz Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth (New York: Grove, 2004), esp. 97–144. Although Fanon’s conceptualization of liberation and revolution exceeds this essay’s margins, it is important to MBN’s performance that Fanon does not equate explosions with revolution and sees decolonialism as a viciously cyclical process. ↵

- David Marriott, “Waiting to Fall,” New Centennial Review 13, no. 3 (2013): 175. ↵

- Fanon, Black Skins, White Masks, trans. Philcox, 119. ↵

- Kara Keeling, The Witch’s Flight: The Cinematic, the Black Femme, and the Image of Common Sense (Durham, NC: Duke University of Press, 2007), 37. ↵

- Kara Keeling, Queer Times, Black Futures (New York: New York University Press, 2019), 81–106. ↵

- Keeling, The Witch’s Flight, 40. ↵

- Thanks to Hélène Valance and Tatsiana Zhurauliova for the turn of phrase and their generous support to develop these thoughts. ↵

- Saidiya Hartman, “The Belly of the World: A Note on Black Women’s Labors,” Souls 18, no. 1 (2016): 171. ↵

- O’Grady, “Mlle Bourgeoise Noire 1955,” 10. ↵

About the Author(s): José B. Segebre Salazar is doctoral candidate in the Department of Philosophy/ Aesthetics, Hochschule für Gestaltung in Offenbach am Main in Germany.