Asian American Art and the Obligation of Museums

Conclusion to Asian American Art, Pasts and Futures

Consider one object by Japanese-born artist Toshio Aoki (1854–1912), acquired by the Cantor Arts Center at Stanford University from The Michael Donald Brown Collection, an 1895 painting, Persimmons in an Indian Basket (fig. 1).1 In the only known oil by Aoki, ripe persimmons are seen spilling out of a basket of presumably Indigenous design onto a russet-brown ground. It is composed in keeping with conventions of traditional still-life painting, but Persimmons is an unusual work for both Aoki and American art history. The rest of Aoki’s oeuvre (what remains of it) comprises ink and watercolor nihonga-style compositions (fig. 2). This anomalous venture into oil painting—often considered a western medium—affords a unique opportunity. Its syncretic subject matter alludes to Aoki’s heritage as a Japanese immigrant and his new home in California. The rounded teardrop forms of the coral-orange fruits indicate that they are likely the Hachiya persimmon, a variety brought to California from Japan in the mid-nineteenth century.2 The only other compositional element of this painting is an Indigenous woven basket. What is Aoki’s inclusion of this basket meant to signal? By choosing to represent it, is he obliquely alluding to the ongoing presence of Indigenous people in the United States, during a moment when there were violent attempts at their physical and cultural erasure? When looked at together, these compositional elements form a modest cornucopia of interpretative possibility: a vessel crafted by the original occupants of California soil cradling fruits of Japanese export. Among the first documented artists of Japanese descent to forge a career in the United States, in his lifetime, Aoki was known for watercolors, illustrations, and design work. Despite his success and counting J. P. Morgan and J. D. Rockefeller among his social circle, his work remains largely absent from museum collections.3

Aoki is one of the most significant early artists of Asian descent working in the United States, although his work does not fetch high prices in the commercial art market. The market for Asian American art, as opposed to other collecting areas—contemporary art, Old Master painting, midcentury American abstraction—is slim. Outside of a few relatively well-known artists, such as Ruth Asawa (1926–2013) or Nam June Paik (1932–2006), most objects made by Asian Americans do not command comparatively high prices at auction or from gallery sales (when they appear in these venues at all). There is a minimal market for Asian American art, especially historical objects (pre-1950).4 Collecting institutions, such as museums, have the unique capacity to acquire and provide long-term care for art objects. As with any acquiring museum, the market value or asking price of a potential purchase plays a major role in an institution’s ability to acquire it.5 Generally speaking, lower price tags should help museums, with their mostly limited acquisition budgets, acquire work by Asian American artists. Why is it, then, that so few museums have work by these artists in their collections?

Several complex and intersecting reasons might explain the lack of institutional representation of Asian American art; market interest is but one metric for understanding the full value of any object. Even so, what does this deficiency of market interest tell us about the historical exclusion of Asian American art from museums, mainstream art institutions, and scholarship? As the financial worth of an object is often not commensurate with its historical or intellectual significance (in fact these forms of value are essentially irreconcilable), there is a tendency in academic scholarship to ignore the monetary value of an artwork. An emphasis on the market value of an object also reifies an inequitable capitalist system aimed at profit, not the preservation of histories or people. But, in the case of Asian American art, this underappreciation of market value is significant and speaks to the institutional invisibility of Asian American art at large. The lack of Asian American representation in the larger art world economy has certainly impacted what and how knowledge about it has been produced and disseminated—if art objects are not available on the market or within museum collections it is difficult to know what actually exists. Networks of contact and engagement among artists, curators, art historians, gallerists, collectors, auction houses, and dealers help shape and define the overall value of an art object or field of art. Asian American art has been undervalued in almost every major arena of the art world: art-historical scholarship, museum collections and displays, and the art market. Is it going too far to say that Asian American art has never been considered valuable? If this is the case, would it be that surprising, given the pervasive whiteness of the art world?6

Aoki’s Persimmons is one object of one hundred forty-one works acquired from Michael Donald Brown for the Cantor Arts Center as part of the Asian American Art Initiative (AAAI). Michael Donald Brown (1947–2019) was a Bay Area art dealer and collector specializing in Asian American art, particularly art made in California by artists of Asian descent. Over the course of more than thirty years, Brown amassed a singular collection, working with the families of many artists to collect oral histories and archival materials.7 He placed work with museums such as the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, although he could not convince any institution to acquire a significant number of objects from his collection, which numbered in the hundreds.

Like many objects from the Brown collection, Persimmons is a painting of latent disruptive potential. Aoki utilizes the materials and conventions of a genre dominated by white western artists to fold together Indigenous and immigrant histories, alluding to important topics of current interest: migration, settler colonialism, and their intersections. What could museum galleries of American art accomplish if work such as Aoki’s were more represented? What would it say about who was making art in the United States and when they were making it? How would the interpretive possibilities present in paintings such as Aoki’s challenge our thinking about nationhood, belonging, and the construction of the American artistic canon?

Private collections and artists’ families hold a significant concentration, if not the majority of, Asian American art in the United States. There are undoubtedly valid critiques to be made regarding the politics and ramifications of Brown, a white art dealer, accumulating a collection of work by nonwhite artists. This paradigm, however, is common in the art world and should be of no surprise, given the concentration of wealth in the United States. However racially and economically problematic, through his persistent collecting done in collaboration with many artists’ families, Michael Donald Brown surely saved a meaningful number of artworks from certain obscurity—although as a private collector, he was not obligated to make his collection accessible to researchers or the public, he ultimately did so.

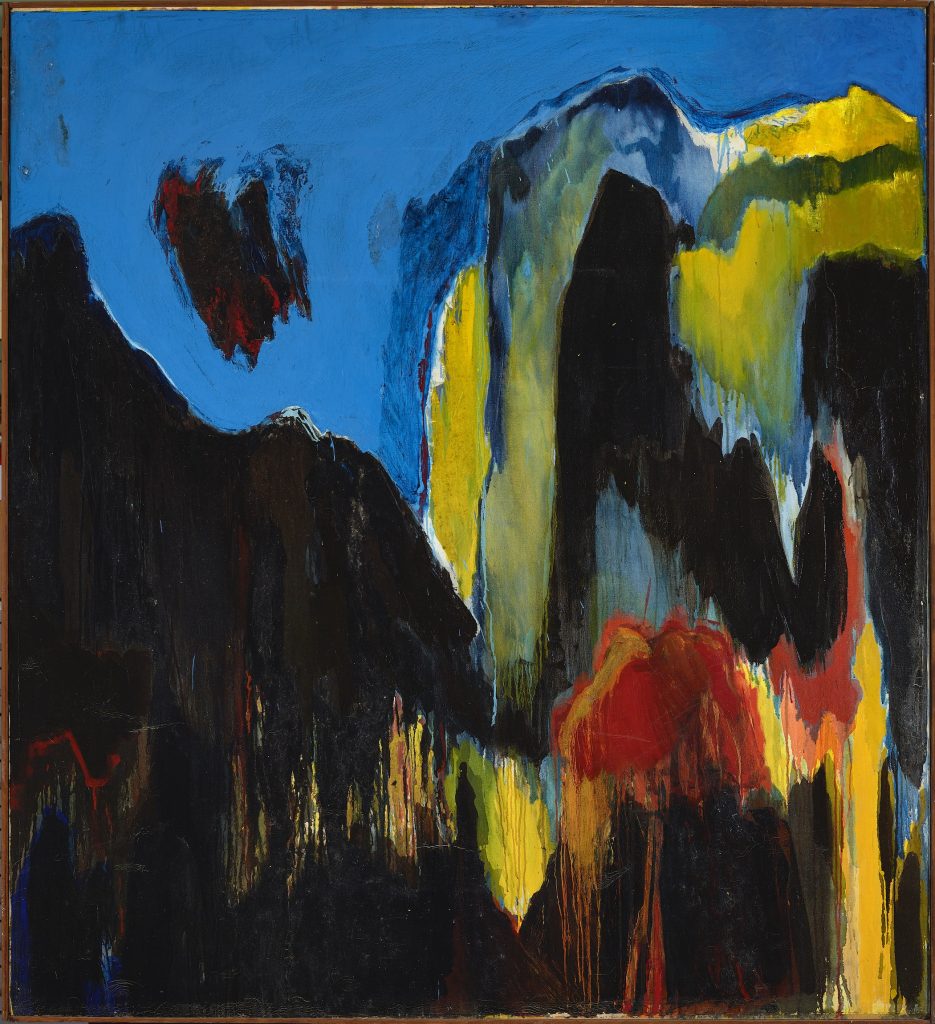

Artists might choose to sell their work to collectors and dealers for several reasons: monetary gain, enhanced reputation, exposure, and even personal storage limitations. This latter circumstance is a common struggle for many artists, as they often face difficulty finding adequate—not necessarily ideal—storage conditions for their output. At the expense of their long-term art-historical reception, this can lead to artists and their estates selling off art objects in a piecemeal and haphazard manner or relying on the generosity of others to help store work. For example, queer Chinese American artist Bernice Bing (1936–1998) stored her paintings at friends’ homes or at SOMArts Cultural Center, where she served as the first executive director.8 A student of Richard Diebenkorn and Saburo Hasegawa, Bing was a prominent artist and arts advocate in the extended Bay Area during the latter half of the twentieth century, although her work remains largely nonexistent within art-historical narratives and museum collections. Blue Mountain No. 4 (fig. 3), a significant painting given to the Cantor Arts Center by Bing’s estate, was severely damaged in a storage fire. In 1998, while in failing health, Bing worked with a conservator who donated his services to help repair the painting.9 Anecdotes such as these, where community members —whether they be fellow artists, dealers, conservators, or simply friends—vitally assist in the care of work by Asian American artists, are numerous. One may surmise that the material and economic struggles Bing faced during her lifetime have considerably impacted the visibility of her work in academia and museums, as the search for the entirety of Bing’s oeuvre is ongoing. The estate continues to locate paintings previously unknown or considered lost.

We may consider Bing’s predicament as unfortunately common for many Asian American artists, especially those of earlier generations. Fold in the material impact of the forcible incarceration of Japanese Americans under Executive Order 9066 (as just one other historical example) and we can begin to get a sense of the many threats that have faced and continue to face the preservation of Asian American art. In 1942, (George) Matsusaburō Hibi (1886–1947) gave the majority of his oeuvre to the city of Hayward before it was mandated that he relocate to the Tanforan Assembly Center and later the Topaz Relocation Center (fig. 4).10 After the end of the war, most of Hibi’s paintings stored in Hayward could not be located. In the art world, the complexity of issues surrounding provenance, racial equity, and cultural visibility are myriad, and the distribution of power between artists, collectors, and museums is almost never equitable. Until recently, when it comes to collecting, caring for, and displaying Asian American art, art museums are often absent from these narratives. Frankly, art museums have done comparatively little toward the long-term preservation of Asian American art.

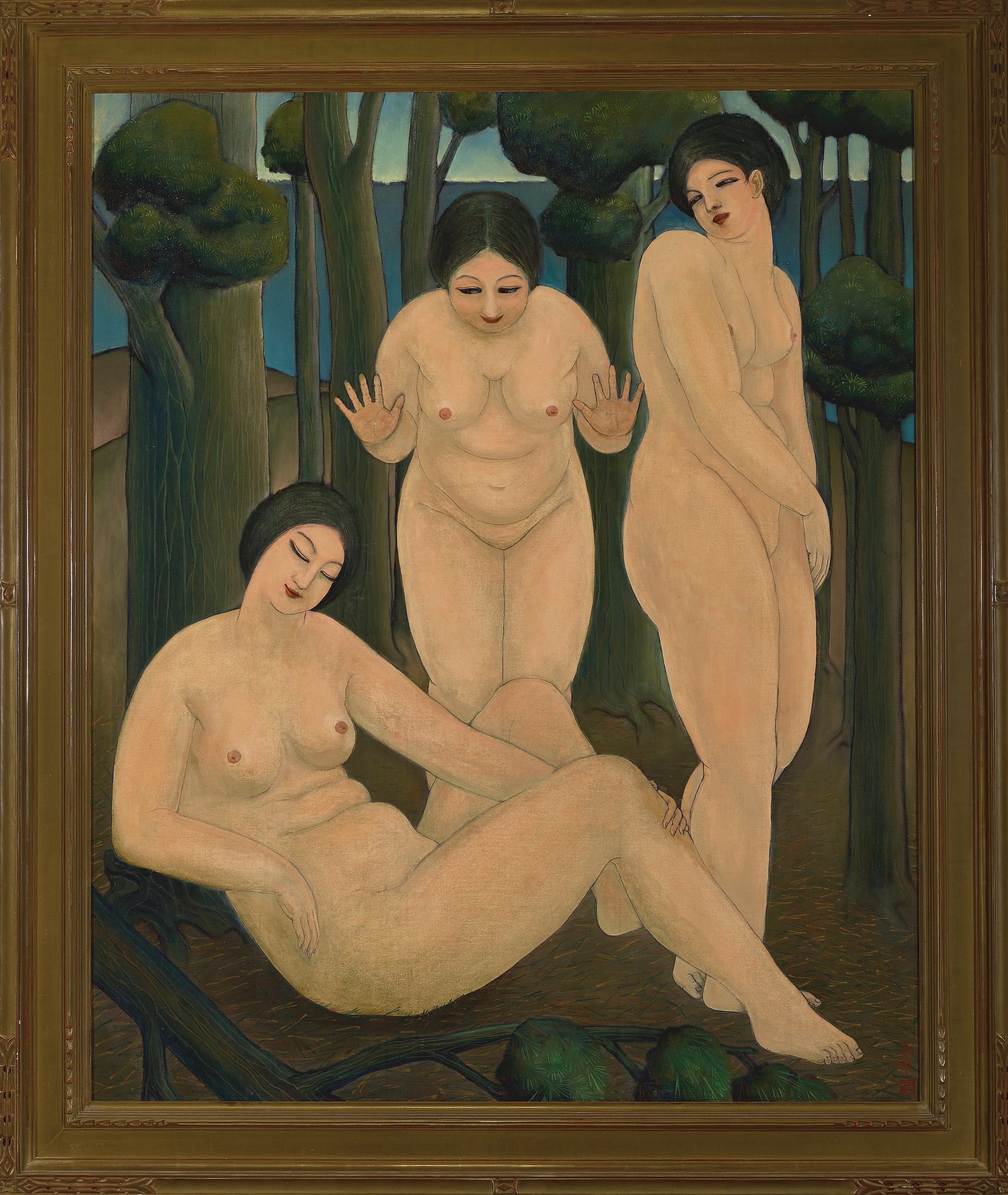

In part because of this lack of museum support, Asian Americans have served as their own arts advocates, forming collectives and structures to support their work when mainstream institutions would not.11 In the Bay Area, the Kearny Street Workshop (KSW) was established in 1972 and is the oldest Asian American and Pacific Islander arts organization in the United States. Founded in the First International Hotel (I-Hotel) by early organizers of the Asian American movement, the KSW opened the Jackson Street Gallery in 1974, an adjacent art space that hosted exhibitions, readings, and events. In 1989, after the national meeting for the Women’s Caucus for Art, the Asian American Women Artists Association (AAWAA) was established by Betty Kano, Flo Oy Wong, and Moira Roth in San Francisco (fig. 5).12 Bing joined the group soon after. AAWAA is unique as one of the only arts organizations in the United States explicitly created to support Asian American women artists. Beyond organizing exhibitions and public programs, AAWAA also runs the Emerging Curators Program, which offers opportunities for Asian American women to gain experience in the curatorial realm. For AAWAA and many other Asian American art collectives, it is not just the representation of Asian Americans on museum walls that matters; they recognize the need for Asian Americans to occupy important roles as public and creative leaders within institutions and beyond.

On the east coast, the Asian American Arts Centre (established in 1974) and Godzilla: Asian American Arts Network (established in 1990) both serve(d) as important community-based organizations that have significantly supported artists in the form of exhibitions, public programs, and professional networking.13 Founded by a group of artists and curators that include Karen Higa, Tomie Arai, Margo Machida, Byron Kim, and Eugenie Tsai, Godzilla was profoundly important for Asian American art and history. Before they disbanded in 2001, Godzilla printed a national newsletter that covered issues relating to Asian American art and culture and helped organize important exhibitions such as The New World Order III: The Curio Shop at the Artists Space in New York City. In 1991, they famously published a letter calling attention to the lack of Asian American artists represented in the Whitney Biennial. These efforts helped secure a place for Asian American artists, including Kim, in the 1993 Whitney Biennial.14 And, in 1994, Tsai was appointed as a curator at the Whitney Museum of American Art.

With the exception of the Asian American Art Centre, these organizations, like many community organizations, do not have the capacity to collect, and if they do, that capacity is limited. The strengths of these collectives are their ability to provide direct support and offer platforms for community members, organize around activist causes, and feature emerging talent. Proper long-term care, storage, and display of objects is a costly enterprise and often beyond the means of grassroots organizations—moreover, the burden should not be exclusively on these collectives to do so. Museums have a communal and historical obligation to find sustainable methods of non-extractive partnership with such organizations if they are truly invested in representing artists who have been historically excluded from their spaces.

Major museum and institutional interventions surrounding Asian American art have occurred primarily in the format of large-scale, loan-based, sometimes traveling exhibitions. Within the last thirty years, artists, curators, and scholars such as Machida, Higa, Carlos Villa, Mark Dean Johnson, Melissa Chiu, Susette S. Min, Christine Y. Kim, and ShiPu Wang have organized groundbreaking shows of Asian American and Asian diasporic art. In the wake of conversations surrounding multiculturalism in the 1980s and 1990s, these figures critically engaged with the idea of identity-based exhibitions, driving dialogue beyond representational celebration and recuperation. Two prominent exhibitions were hosted at the Asia Society in New York City: Asia/America: Identities in Contemporary Asian American Art (1994) and One Way or Another: Asian American Art Now (2006).15 Curated by Machida, Asia/America was the first significant exhibition of Asian American art mounted by the Asia Society, which typically featured art from the Asian continent and not the diaspora. One Way or Another was seen as a kind of follow-up to Asia/America, seeking to put even more pressure on what, exactly, an ethnically defined exhibition can accomplish. It featured seventeen contemporary artists, many of whom did not identify as Asian American.16 In Min’s essay for the catalogue, “The Last Asian American Exhibition in the Whole Entire World,” she ponders what it might mean to unmoor Asian American art from race-based assumptions and interpretations.17 A common thread in both of these shows is the self-conscious recognition of the downfalls of the racially organized exhibition model while simultaneously engaging with it. How to feature Asian American art in a museum space without making identity-based interpretations the primary mode of engagement? How to express that this art matters not just because it is made by Asian Americans, although that fact itself bears acknowledgment in some form?

Two major forces in the Bay Area art world who have organized numerous significant exhibitions and projects surrounding Asian American/Asian diasporic art are Villa and Johnson. Villa and Johnson were faculty members at the San Francisco Art Institute, where Villa also received his BFA. While primarily known for his diverse artistic practice, Villa was also a curator and cultural organizer, his influence stretching far and wide across the region.18 In 1976, Villa put together the expansive exhibition Other Sources: An American Essay as a radical rejoinder to the celebrations surrounding the American bicentennial.19 Villa, a Filipino American, curated a sprawling selection of work by a diverse array of artists, then called “Third World artists,” including Asawa, Bing, Robert Colescott, Mary Lovelace O’Neil, Linda Lomahaftewa, and James Suzuki. Mounted at the San Francisco Art Institute, this exhibition and its accompanying programming was in the spirit of what would later be commonly known as multiculturalism, featuring artists whose primary influences were not the western artistic canon. Villa’s last project, Rehistoricizing the Time around Abstract Expressionism in the San Francisco Bay Area, 1950s–1960s, revisited topics he addressed in Other Sources thirty-five years earlier, recontextualized for a “post-race” world. It debuted at the Luggage Store in 2010 and is still available as an online resource.20 Long before discussions of decolonizing the museum space became part of public discourse, Villa’s curatorial work modeled what such practice could look like within and beyond institutional walls.

Working with Irene Poon Anderson, Dawn Nakanishi, and Diane Tani, art historian and curator Johnson helped organize the first survey exhibition of early Asian American artistic production in 1995. Mounted at San Francisco State University, where Johnson is now a faculty member, With New Eyes: Towards an Asian American Art History in the West, contained about one hundred objects—many of which had never been exhibited before. Johnson expanded upon this exhibition more than thirteen years later when he guest-curated the groundbreaking show, Asian/American/Modern: Shifting Currents, 1900–1970, at the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.21 While there had been some national interest in the work of contemporary Asian American art up until this point, Johnson’s community-oriented excavations of the long history of Asian American artistic production proved groundbreaking in the field. The cumulative impact of Johnson’s curatorial work, which stretches far beyond these two examples, has necessarily expanded the field of American art.22

The aforementioned exhibitions are by no means intended to comprise a comprehensive list of significant shows featuring Asian American and Asian diasporic art in the United States. Instead, they are a very limited selection of key moments, from both the east and west coasts, where Asian American art occupied a narrow spotlight in the art world. Unfortunately, the spotlight shines infrequently on the work of Asian American artists. These large exhibitions, which require borrowing artworks from many different parties, are complicated endeavors that require a significant application of resources from museums, artists, gallerists, collectors, donors, and community members. It takes a small village to make an exhibition happen. Even so, the application of resources toward a temporary exhibition is a finite, and not an ongoing, institutional investment. Hosting a major exhibition of Asian American art is not the same type of investment as actively building, conserving, storing, and exhibiting it. A curatorial position within the museum also impacts an institution’s future investment in the material. Johnson was a guest curator at the de Young when he organized the exhibition, Asian/American/Modern—not a permanent staff member—so as much as he might serve as an advocate for Asian American art, his role within the institution had an expiration date.

In 2020, Min returned to her earlier queries about the need and value of multicultural, postcolonial, and geographically, ethnically, and racially specific survey exhibitions such as Asian/American/Modern. In “Refusing the Call for Recognition,” Min describes them as an “outmoded curatorial artifact that emerges every decade as the go-to remedy to ‘fix’ racism and the under-representation of a certain group of artists.” It is undoubtedly true that these types of exhibitions are often weaponized in this way, used as token examples, occurring once every few years, to demonstrate that a museum exhibits more than just the work of white male artists. By labeling an object as Asian American, one is burdening it with a set of premade interpretations, effectively limiting the viewer’s imagination.23 Therefore, according to Min, such racially specific group shows often end up being critically limited, shallow, and prescriptive interventions of diluted impact. Is there a future where this is not the case? Does assimilating so-called Asian American objects into a museum logic help or harm?

Collection building is not the ultimate or only solution to issues facing Asian American art and history. One can argue that building art collections within museums reinforces their imperialist origins, consolidating their power and ability to hoard culture, and further sutures together the relationship between race, capitalism, and representation.24 Moreover, museums can also acquire art and banish it to storage (though even in storage, scholars are generally still able to access objects by appointment). Unless there are specific acquisition stipulations that necessitate the display of an object, a museum is under no obligation to show it. If there is not a curator on staff who is invested in the material and dedicated to its research and presentation, there is a high risk of these objects being trapped in storage purgatory. Even still, we should consider that for hundreds of years, museums have devoted their resources to the collection, preservation, research, and display of work by very select groups of predominantly white male artists—and generally speaking, this is still the case. It is significant that even in 2021, few major US institutions collect the work of Asian American artists with enthusiasm or rigor. What does this say about the institutional value of Asian American art? Or where museums choose to invest their resources?

A noteworthy exception is the Smithsonian American Art Museum (SAAM), which has one of the only substantial collections of Asian American art. Within the last five years, SAAM has mounted and supported a number of focused exhibitions featuring Asian American and Asian diasporic artists: Chiura Obata: American Modern (2019); Tiffany Chung: Vietnam, Past is Prologue (2019); Do Ho Suh: Almost Home (2018); Isamu Noguchi, Archaic/Modern (2016); The Artistic Journey of Yasuo Kuniyoshi (2015); and Nam June Paik: Global Visionary (2013). These are somewhat recent developments; nonetheless, these exhibitions, which often draw on SAAM’s permanent collection, are scholarly and appealing exhibitions that thoroughly enrich our understanding of artistic production in the United States.25 As remarkable as these efforts are, one might also ask: is it not SAAM’s obligation, as a museum dedicated exclusively to the acquisition, promotion, and interpretation of the work of artists in the United States, to thoroughly represent Asian American art? Should we applaud a museum for doing what it should be doing in the first place?

These questions and issues surrounding the role of museums and Asian American art are not new, having been observed by previous generations of scholars in Asian American studies. In 1990, Machida writes: “At present, no museum-scale setting is exclusively devoted to reflecting the richness and diversity of contemporary visual arts emanating from our various communities and generational groups—each with separate traditions, beliefs, and immigrant histories.”26 She goes on to say that, similarly to how other historically excluded ethnic and racial groups have benefited from the formation of supportive museums and institutions (such as the Studio Museum in Harlem), Asian Americans might benefit from such support and visibility in the cultural sphere. In 2021, Machida’s observation remains true: there is still no institution exclusively devoted to the collection, preservation, and display of either historical or contemporary Asian American art.

The Cantor Arts Center at Stanford University is an encyclopedic museum, and therefore it cannot be exclusively devoted to Asian American art, but it does seek to offer resources for the long-term collection and care of Asian American and Asian diasporic art through the AAAI. The AAAI, founded and codirected by the editors of this In the Round, seeks to make the Cantor Art Center and Stanford University one of the preeminent national study centers for Asian American Art. In order to do so, a significant component of the AAAI must be the ongoing formation of an expansive collection of art from the Asian diaspora. As the AAAI is a collaborative project housed within the Cantor Arts Center, an actively acquiring university art museum, building a collection of this material is possible.27 The AAAI considers “Asian American” to be a heterogeneous, relational, and expansive term, applying to a vast variety of art objects made within and beyond the borders of the United States. Its genesis came from a desire to address the very real existential and practical threats facing the survival of Asian American art—there is still so much material from the larger diaspora that requires institutional investment and support to secure its future. Furthermore, a primary aim of the AAAI is to render this material accessible to museum visitors, students, the scholarly community, and the general public. The objective is to provide meaningful encounters with objects that reshape the collective understanding of this field called American art. We want it to be known that Asian American art exists; that it is valuable in every respect—even if it has not been treated as such—and has a future of limitless possibility owing to the ongoing research of invested curators and scholars of today and tomorrow.

While developing the AAAI, the codirectors heard (and continue to hear) numerous stories from community members about how difficult it has been to locate ongoing support for their collections, archives, and individual works of Asian American art. Ibuki Lee, daughter of artists Hisako Shimizu Hibi (1907–1991) (fig. 6) and (George) Matsusaburō Hibi, recently shared that she once found, at a garage sale, a painting her mother created while interned at Topaz, and that she also found another of her mother’s paintings on eBay.28 Anecdotes such as these convey the urgency and necessity of a project such as the AAAI. And while it remains a significant and crucial part, the AAAI is not just about the visibility and representation of Asian American artists in the museum space; representation is but one star in a larger constellation of goals. The AAAI wishes to support Asian American artists and the communities that sustained, cared for, and loved them during their lifetimes, and the subsequent generations that keep their memories alive. It honors and acknowledges the Chinese laborers who built the Stanford University campus and the Cantor Arts Center. The AAAI is about fulfilling an obligation—a debt. Marci Kwon and I understand that we have the great privilege and honor to do so.

As codirector of this initiative, it is worth noting that I did not study Asian American Art in my doctoral work. Throughout my undergraduate career, I do not recall encountering the work of a single Asian American artist, which certainly impacted my areas of interest while applying to graduate school. The material did not seem to exist. I did not see it in museums. I did not know of figures such as Aoki, Bing, or Asawa. At the beginning of this essay I asked, “What could museum galleries of American art accomplish if works like Aoki’s were more represented?” In truth, this question emerges from two vantage points: my current role as a curator at a university art museum and my past self, just becoming interested in art history. For what I am secretly inquiring is, “What would have an encounter with Aoki’s painting done for my younger self?”

Let us end with a work that exemplifies the importance of community, representation, and preservation for Asian American artists by Ruth Asawa: Untitled (LC. 012, Wall of Masks) (fig. 7). Asawa was a key figure in the Bay Area art world, but only toward the end of her life was her wide-ranging artistic practice nationally recognized by mainstream art institutions—museums, auction houses, and galleries—as deeply revolutionary and valuable.29 In 1965, Asawa began casting in plaster the faces of friends, family, and art world colleagues, learning the method from a public school art teacher. From these plaster impressions, she created ceramic positives and fired them in her home kiln, often creating multiples so she could keep one and give an impression to the sitter (she made more than three hundred individual masks). Created in a range of clay bodies that mimic various skin tones, these hauntingly lifelike face masks hung on the exterior of Asawa’s wood-shingle Noe Valley home. These faces welcomed visitors to Asawa’s most intimate space: her studio and the home she shared with her husband, Albert Lanier, and their six children. Asawa captured many faces, including those of John Gutmann, Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence, and Billy Taylor, as well as her children at different stages of their lives. There was no difference between capturing the face of a well-known artist and an elementary school student. People—their lives, faces, and stories—mattered to Asawa. In speaking about this project, Asawa reflected on its appeal:

So when I cast a face I know I’m just capturing a minute of a person. Or if I cast a foot of a baby I know that baby’s foot will grow and grow and grow. But at the moment I like that. That moment that I caught in a way is what I like about casting faces. I don’t care about making that a technique. But I like the idea of stopping the moment of a time. And it’s going to disappear.30

Perhaps we may heed Asawa’s words and example to understand that art objects, such as Aoki’s Persimmons in an Indian Basket and Bing’s Blue Mountain No. 4, are fixed moments in time, the material vestiges of an important history of Asian American artistic production. It is a history that is too often overlooked, underappreciated, and made invisible by powerful institutions. If institutions do not care for these materials, past, present, and future, they will disappear. As much as communities have tried to preserve it, an unquantifiable amount of Asian American art has already been lost. Museums have moral obligations: they must prevent further such disappearances from happening, make history and its objects accessible, and care for the communities they are meant to serve but have historically neglected—such as Asian Americans.

Cite this article: Aleesa Pitchamarn Alexander, “Asian American Art and the Obligation of Museums,” conclusion to “Asian American Art, Pasts and Futures,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 7, no. 1 (Spring 2021), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.11465.

PDF: Alexander, Asian American Art and the Obligation of Museums

Notes

- It is unclear whether the title was assigned by Aoki, a previous collector/dealer, or Michael Donald Brown. “Indian” is no longer an acceptable term used to describe Indigenous people of North America but is kept in this context, as it is the current title associated with the painting. The basket appears to be of Indigenous design. However, as it is unknown if Aoki painted this from life or invented the composition, I hesitate to say an Indigenous person made the basket. More research is needed on the provenance and circumstances of production of this painting. ↵

- The American persimmon (Diospyros virginiana) is rounder and squatter in shape and typically grows from the Gulf region through the midwest and northeast. Julia Morton, “Japanese Persimmon,” The Fruits of Warm Climates (Miami: Florida Flair Books, 1987), 411–16. ↵

- For more about Toshio Aoki’s career, see Chelsea Foxwell, “Crossings and Dislocations: Toshio Aoki (1854–1912), A Japanese Artist in California,” Nineteenth Century Art Worldwide 11, no. 3 (Autumn 2012), http://www.19thc-artworldwide.org/autumn12/foxwell-toshio-aoki-a-japanese-artist-in-california. ↵

- In a recent auction search, a large Ruth Asawa wire sculpture from about 1960 sold at Phillips New York for $3,539,000 (December 7, 2020). An early portrait by Miki Hayakawa, Self Portrait: Homage a Cezanne, c. 1924, sold at Bonhams Los Angeles for $5,250 (November 2017). In many cases, early Asian American artists, such as Tameya Kagi and (George) Matsusaburō Hibi, have limited to no auction record history. These examples, among many, indicate that there is limited market interest and/or availability of Asian American art pre-1950. The secondary market value of a work of art is often a strong indicator of interest in an artist or area of art—the fact that it can be purchased from an artist or gallery and later sold at a higher valuation points to an appreciation of fiscal value. In some cases, especially with regard to historical Asian American art, there is a depreciation of monetary value over time, which makes it less attractive to collectors interested in reselling the work. ↵

- This primarily applies to purchases of art, not acquisitions through gifts and bequests. ↵

- The 2018 Art Museum Demographic Survey conducted by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, Ithaka S + R, and the Association of American Museum Directors indicates that 84 percent of curators, 89 percent of conservators, 74 percent of educators, and 88 percent of museum leadership identify as white.Three percent of Asian-identifying people and less than 1 percent of Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islanders hold intellectual leadership positions in American museums. According to 2019 census data, Asian Americans make up 5.7 percent and Pacific Islanders 0.5 percent of the U.S. population. The area where the most nonwhite people are hired into intellectual leadership positions are education departments. These numbers are an improvement from the same survey conducted in 2015. When it comes to the representation of nonwhite artists in museum collections, a 2019 paper surveyed the collections of eighteen major US art institutions to find that 85 percent of artists were white and 87 percent were male. Importantly, they find that “the relationship between museum collection mission and artist diversity is weak, suggesting that a museum wishing to increase diversity might do so without changing its emphases on specific time periods and regions.” Mariët Westermann, Roger Schonfeld, and Liam Sweeney, “Art Museum Staff Demographic Survey 2018,” The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, 2019; and Chad M. Topaz et al., “Diversity of Artists in Major U.S. Museum Collections,” PLOS ONE, March 19, 2019, https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0212852. ↵

- Brown self-published a small volume about his collection. By the time the Cantor Arts Center was able to acquire work, many objects represented in the book, including a work by Ruth Asawa and Hisako Hibi’s internment paintings, were no longer part of his collection. Michael Brown, Views from Asian California: 1920–1965, An Illustrated History (self-published, 1992). ↵

- Jennifer Banta, “The Painting in the Rafters: Refiguring Abstract Expressionist Bernice Bing,” Bingo: The Life and Art of Bernice Bing (Sonoma, CA: Sonoma Valley Museum of Art, 2019), 23. ↵

- Nancy Chaffin (consultant for the estate of Bernice Bing) and Dennis Calabi (independent conservator), to the author, November 2020. Even with this previous conservation work, Blue Mountain No. 4 still requires significant treatment in order to bring it to museum presentation quality. While institutions can receive generous gifts such as this one, conservation is a costly enterprise. In the case of this particular painting, the cost to treat it exceeds its market value. ↵

- In collaboration with artist Chiura Obata (1885–1975), Hibi helped create an art school for the incarcerated at both Tanforan and Topaz, which enrolled more than six hundred students. ↵

- “Community-based Asian American arts organizations continue to provide a leadership role by exhibiting and publicizing our visual artists. Yet, without consistent support and connections that major institutions do provide . . . Asian American have difficulty attracting the attention of those critics, curators, and museum professionals whose verification is often fundamental to making an artist visible to a national audience.” See Margo Machida, “The Need for Scholarship in Documenting Asian American Contributions in Contemporary Art,” Completing the Circle: Six Artists (San Francisco: Southern Exposure Gallery/Triton Museum of Art: 1990), 6–7. ↵

- The AAWAA archive is now in the Special Research Collections at the University of California, Santa Barbara. As part of the Bing gift to the Cantor, the estate of Bernice Bing also gifted her archive to Stanford University Special Collections. Vanessa Kam, “Announcing the Archive of the Visual Artist Bernice Bing,” Stanford Libraries Blog, September 24, 2020, https://library.stanford.edu/blogs/stanford-libraries-blog/2020/09/announcing-archive-visual-artist-bernice-bing. ↵

- This is not a complete list of relevant organizations and collectives. It is meant to highlight the impact of these few, in order to demonstrate the kind of work these groups are able to accomplish and what kinds of support they can provide. ↵

- This inclusion came with its own cost, as a number of white critics dubbed it the “political” biennial because representation and social issues were among the exhibition priorities. Michael Kimmelman penned an angry and dismissive review, stating: “The Whitney Biennial has not spontaneously brought about world peace and racial harmony, as it seems hellbent on proving it can do,” and “I hate the show.” Robert Hughes declared it “preachy and political.” Michael Kimmelman, “Art View: At the Whitney, Sound, Fury, and Little Else,” New York Times, April 25, 1993, https://www.nytimes.com/1993/04/25/arts/art-view-at-the-whitney-sound-fury-and-little-else.html; and Robert Hughes, “Art: The Whitney Biennial: A Fiesta of Whining,” Time, March 22, 1993, http://content.time.com/time/subscriber/article/0,33009,978001,00.html. ↵

- Melissa Chiu, Karen Higa, and Susette Min, One Way or Another: Asian American Art Now, exh. cat. (New York: Asia Society, 2006). ↵

- Min, “The Last Asian American Exhibition in the Whole World,” in One Way or Another, 39. ↵

- Min, “The Last Asian American Exhibition in the Whole World,” 34–41. ↵

- Notably, Villa’s cousin and earliest artistic mentor was his cousin, the painter Leo Valledor. ↵

- Paul Kawaga et al., Other Sources: An American Essay (San Francisco: San Francisco Art Institute, 1976). See also Mark Johnson, “1976 and Its Legacy: Other Sources: An American Essay at the San Francisco Art Institute,” Art Practical, September 11, 2013, https://www.artpractical.com/feature/other-sources. ↵

- “Rehistoricizing Abstract Expressionism in the Bay Area Symposium,” http://rehistoricizing.org. ↵

- Daniell Cornell and Mark Dean Johnson, Asian/American/Modern: Shifting Currents, 1900–1970, exh. cat. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2008). The Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco has a history of mounting exhibitions featuring Asian American art—in that it has a history at all—unlike many other large civic art museums. ↵

- Mark Dean Johnson also serves as an advisor to the Asian American Art Initiative at the Cantor Arts Center at Stanford University. ↵

- Susette Min, “Refusing the Call for Recognition,” Panorama: The Journal for the Association of Historians of American Art 6, no. 2 (Fall 2020), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.10960. She also discusses these issues at greater length in her book, Unnamable: The Ends of Asian American Art (New York: New York University Press, 2018). ↵

- Alice Procter, The Whole Picture: The Colonial Story of Art in Our Museums and Why We Need to Talk about it (London: Octopus Publishing Group, 2020) is an excellent recent publication on this topic that analyzes a wide range of institutions, collections, and exhibitions from the historical to contemporary. ↵

- If one looks further back into SAAM’s exhibition history, the first exhibition featuring an Asian American artist appears to be a Yasuo Kuniyoshi exhibition presented in 1969. The next exhibition does not appear until 1995, when Kay Sekimachi and her husband Bob Stocksdale are jointly featured in a show, Marriage in Form: Kay Sekimachi and Bob Stocksdale. ↵

- Machida, “The Need for Scholarship in Documenting Asian American Contributions in Contemporary Art,” 7. ↵

- For more on the establishment of the Asian American Art Initiative at the Cantor, see Beth Giudicessi, “Cantor Arts Center Launches Asian American Art Initiative Bolstered by Major Ruth Asawa Acquisition, The Michael Donald Brown Collection and Other Works.” Press Release, January 25, 2021, https://news.stanford.edu/2021/01/25/cantor-arts-center-launches-asian-american-art-initiative; and “Asian American Art Initiative,” website for the Cantor Arts Center, Stanford University, accessed May 14, 2021, https://museum.stanford.edu/AAAI. ↵

- Ibuki Lee to the author, April 14, 2021. ↵

- See the Asawa biography by Marilyn Chase, Everything She Touched: The Life of Ruth Asawa (San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 2020), which opens with a prologue describing a 2013 Christie’s auction where one of Asawa’s large wire sculptures sold for $1.4 million, four or five times its estimated value (at that time). When the sale closed, one of Asawa’s daughters turned to her and proclaimed, “You’re playing with the big boys now!” This anecdote’s placement at the front of her biography, and the tone in which the event is described, implies Asawa’s market success was and is important to the artist and her family. In this text, the sale reified and reflected her historical importance in the American canon, an instance in which a work of art’s historical and commercial value appear aligned. ↵

- Ruth Asawa, transcript of oral history, with Albert Lanier, Paul Karlstrom, and Mark Johnson, 2002, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, 22. ↵

About the Author(s): Aleesa Pitchamarn Alexander is Assistant Curator of American Art and Co-Director of the Asian American Art Initiative, Cantor Arts Center, Stanford University