Reading and Re-Reading Ansel Adams’s My Camera in the National Parks

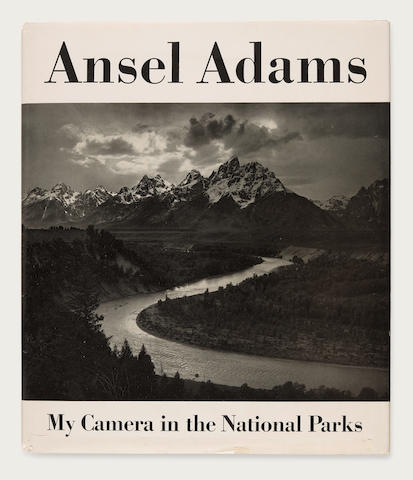

In the fall of 1950, Ansel Adams (1902–1984) published My Camera in the National Parks, a large-format book containing thirty photo engravings depicting national parks and natural monuments across the United States and the territories of Alaska and Hawai‘i. On the dust jacket cover, Adams featured The Teton Range and the Snake River, Grand Teton National Park and Jackson Hole National Monument, Wyoming (fig.1). Today, the image is emblematic of the photographer and his heroic view of the American landscape. It exemplifies Adams’s signature style as it was solidified in the process of the book’s production: an expansive depth of field, an elevated perspective, and a wide tonal range combine to create a powerful and optimistic expression of nature’s beauty.1 In his introductory essay, Adams underscored the “moral sublime” of his images, framing the book as a testament to the significant role nature played in American society and calling on the public to engage with and protect their shared national heritage.2 Published in the wake of the Second World War, the book—and its cover image especially—repeated a well-worn dictum that harnessed the land as a symbol of American strength and resilience in the face of trying times.3

My Camera in the National Parks contains many of Adams’s most celebrated landscapes, and the book is among the photographer’s first conservation-oriented texts intended for wide circulation.4 It helped launch the photographer from niche networks of photography enthusiasts, book collectors, and commercial patrons into a larger popular consciousness, paving the way for the better-known This is the American Earth (1960). It also set the stage for Adams’s now well-accepted status as an individual creative force, an avid conservationist, and the preeminent interpreter of the American landscape. Despite its familiar imagery and its formative role in the photographer’s practice and public persona, the book itself has received little attention. This article offers an initial reading of My Camera in the National Parks, contributing to recent scholarship that recognizes the importance of photobooks, sequencing, and narrative to Adams’s career and the construction of meaning around his images.5

This article also serves as a fundamental re-reading of the photographer, his images, and the cultural work they perform, particularly as they participate in the production and reproduction of the United States as a white settler-nation. Analyzing the project through the lens of settler colonial theory, which recognizes the centrality of material and symbolic acts of erasure, containment, and appropriation as they pertain to Indigenous land and bodies within the process of settler nation-building, I argue that My Camera in the National Parks is intertwined with established and ongoing acts of US imperialism and settler hegemony in the mid-twentieth century.6 Tracking the book’s production from start to finish, I pay particular attention to materiality, aesthetics, and historical context in order to reveal the various layers of engagement and complicity Adams maintained with projects of national expansion in the postwar era.

Although published in 1950, My Camera in the National Parks is an outgrowth of a federal contract Adams received almost a decade earlier, in 1941, to promote the activities of the US Department of the Interior (DOI). Although the Second World War ended the DOI commission less than a year later, it also prompted Adams to assume the imperialist agendas of the United States as his own. Returning to the project independently in the late 1940s with support from a Guggenheim Fellowship, Adams aligned his efforts with the nation’s expanding geopolitical ambitions of the postwar era. Fresh off the Allied victory, political leaders in the United States positioned the nation as the leader of the free world and sought to add two new states into the Union, with postwar campaigns for Alaskan and Hawaiian statehood. Adams’s book, My Camera in the National Parks, underscores how the photographer’s calls for the preservation of the American landscape could also function consciously and unconsciously to affirm US authority, exceptionalism, and dominion. Just as government-sponsored survey photography in the nineteenth century encouraged white settlement and the establishment of the first national parks on Indigenous land, Adams’s book reformulated a “frontier lens” for the expansionist goals of the postwar era, drawing on settler conceptions of time and space to tell a story of the nation as fixed and determined at a moment when it was very much in flux.

Such a reading (and re-reading) of the book follows recent scholarship appearing across disciplines that challenges the idea of the national parks as progressive markers of democracy.7 In our current moment of quarantine, climate change, and the active dismantling of park boundaries, it would be easy to turn to Adams’s My Camera in the National Parks to find comfort and proof of our nation’s ultimate beauty and good. This is exactly how Adams intended the book to function. And yet, as this is also a moment of national self-reflection and reckoning prompted by state-sponsored violence toward Black Americans including Breonna Taylor, George Floyd, and Tony McDade, it is worth thinking through how the national parks and a project like My Camera in the National Parks foreclose social responsibility and actively advance American principles of individualism, control, and ownership that uphold asymmetries of power, past and present.8 Although couched in the beneficent terms of public land, environmental conservation, and natural beauty, the national parks and Adams’s engagement with them reinforce what Aileen Moreton-Robinson identifies as the “possessive logic” of the United States as a patriarchal, white sovereignty, wherein “performative acts of possession” continuously reaffirm the settler nation-state and its whiteness—as the phrase “my camera,” from the title of Adams’s book suggests, for example.9

“What we are fighting for”

In the fall of 1941, the US Department of the Interior commissioned Adams to produce large-scale photo murals for installation in the DOI’s federal headquarters in Washington DC. Throughout October and November of that year, Adams traveled to federal parklands, reservations, and land reclamation projects across the Western and Southwestern states, weaving his work on the DOI’s mural project with commercial assignments and his own creative pursuits. Adams initially sought to document DOI activities broadly, focusing on the recently completed Boulder Dam (today known as Hoover Dam) as well as on Indigenous communities across New Mexico and Arizona. The Japanese attack against the US naval base at Pearl Harbor in Honolulu, Hawai‘i, on December 7, 1941, prompted Adams to shift his attention. He developed a new emphasis for the mural project focused solely on the wilderness spaces of the national parks.10

Joining in the patriotic fervor of the moment—and perhaps fearing that his continued employment might be in jeopardy—Adams wrote to his contact at the DOI, making a case for the significance of the project, given its new theme: “I believe my work relates most efficiently to an emotional presentation of ‘what we are fighting for,’” he asserted.11 The photographer offers no further explanation in his letter regarding how the project might serve this purpose, but it is a sentiment he would repeat months later, even after it had become clear that the agency could not renew his contract. In the early summer of 1942, Adams made one last trip to photograph the national parks of the Northwest, and he sent a summary of his work to the Associate Director of the National Parks Service, in which he again stressed its value. He noted that he had received requests for prints from the Office of the Coordinator of Information, an early intelligence and propaganda agency that would eventually split into the Central Intelligence Agency and the Office of War Information. He added that he had several images that “could make a stunning exhibit of National Park subjects. The Parks are certainly one of the fine things ‘we are fighting for.’”12 In this context, the photographer’s understanding of his images’ usefulness for reflecting a compelling and favorable view of the nation comes into clearer focus. Shortly after this letter, Adams sent the DOI a collection of approximately 220 working prints from the project, but he kept the negatives in hopes that the work might one day be revived in some capacity. As this became increasingly unlikely, Adams began seeking other means of support. Shortly following the war’s end, the photographer applied for and received a prestigious Guggenheim Fellowship to continue his work independently, culminating with the publication of My Camera in the National Parks.

Adams was hardly alone in his swell of support for the nation or in his eagerness to contribute to the war effort, but his desire to harness his work to such ends is significant for a reading of the book. It helps reframe the conservationist aims of My Camera in the National Parks toward a more emphatic nation-building function, one aligned with state myths of exceptionality and strength. With his statement about “what we are fighting for,” Adams began to articulate more fully his belief that the parks were the ultimate expression of American values of democracy and freedom on which the war was waged. The postwar context of the book’s publication witnessed a different kind of battle around these values, one targeted at the “hearts and minds” of people at home and abroad. The Cold War years encouraged Adams to double down on the state-based theme of the project, not only as a patriotic duty but as a mode of self-preservation as well. When members of the New York–based photography organization the Photo League, in which Adams had recently begun to participate, came under the scrutiny of McCarthyism, the photographer turned to his national parks project as a means of distancing himself from the Communist accusations engulfing the group and asserting his Americanism.13 As the photographer wrote when he sent an advance copy of the book to radio commentator Walter Winchell, “I think that every creative person should now direct his energies towards an affirmation of America—each according to his talents and capacities.”14 Adams’s title for My Camera in the National Parks foregrounds his subjective experience in nature, but the book also continued the “fight,” actively legitimizing the nation.

Two photographs that Adams made during his DOI contract are featured significantly in My Camera in the National Parks, and they each underscore the book’s roots as government propaganda and introduce the strategies utilized by the photographer toward this end. Gracing the book’s cover is The Teton Range and the Snake River, which Adams made sometime between May and June 1942 (see fig. 1). As previously mentioned, it is precisely the kind of image that solidified Adams’s postwar rise to fame. The breathtaking view presents the nation as solid, stable, and noble. Yet, at the same time that Adams was traveling through Grand Teton National Park, photographing the parks as symbolic of the freedom and democracy the war was meant to preserve, American citizens and residents of Japanese ancestry in his hometown of San Francisco and across the West Coast were being forcibly removed from their neighborhoods and imprisoned in concentration camps under Executive Order 9066.15 Some of these individuals would be placed at Heart Mountain Relocation Center, just a four-hour drive from the Snake River Overlook, where Adams captured his iconic image. By the fall of 1943, Adams was involved in a project to document the “true Americanism” of incarcerated Japanese Americans closer to home at Manzanar Relocation Center, and here, too, his approach aligned heavily with state narratives about “loyalty” and model citizenship.16 This larger and more complicated national context is unintelligible within the pristine wilderness of The Teton Range and the Snake River.

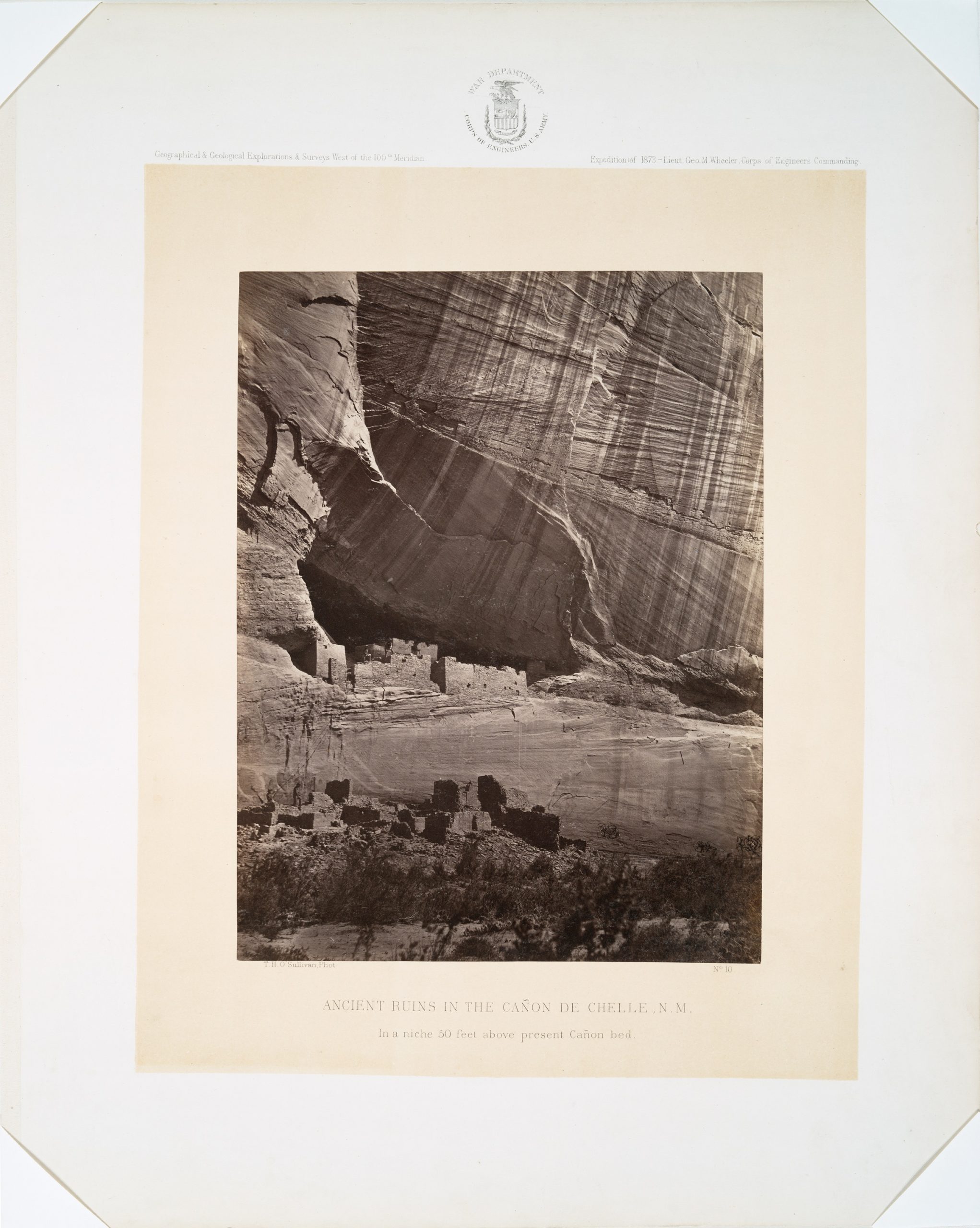

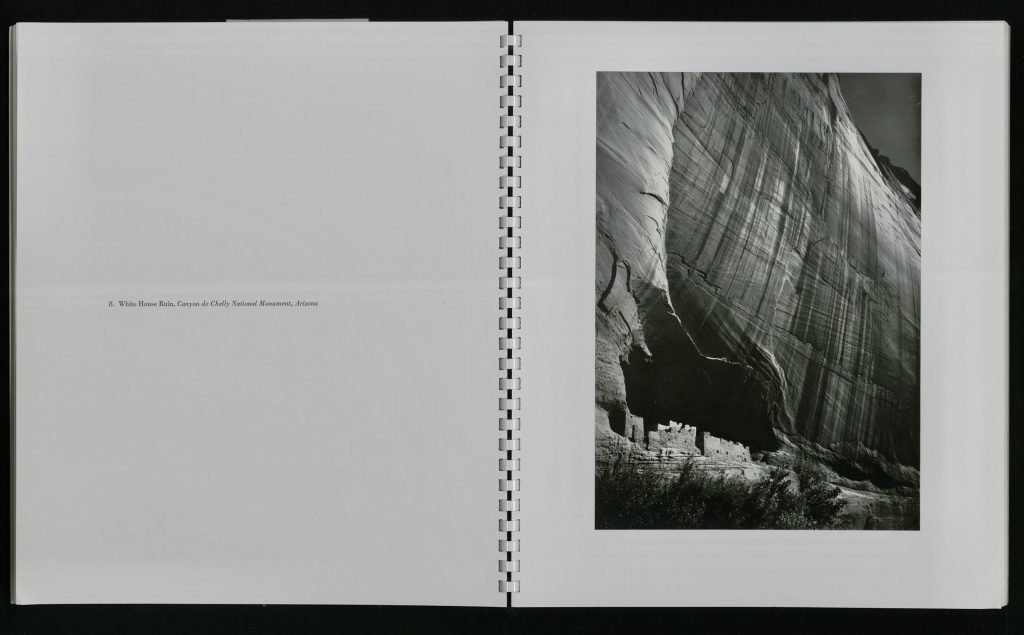

Adams also produced his image White House Ruin, Canyon de Chelly National Monument, Arizona while working for the DOI, and here the photographer draws a direct line between himself and the Western survey photographers of the nineteenth century, who facilitated the initial years of territorial expansion. When the DOI hired Adams, he was in the process of organizing the exhibition Photographs of the American Civil War and Western Frontier with Beaumont Newhall for the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York.17 The MoMA exhibition included an album of photographs by Timothy O’Sullivan documenting state-sponsored expeditions during the 1870s. Adams acquired this album for his personal collection and subsequently donated it to MoMA on the occasion of the exhibition. The photographer was particularly fond of O’Sullivan’s Ancient Ruins in the Cañon de Chelle, and, similarly working under government contract, he enthusiastically re-created this scene in October 1941, photographing the cliff dwellings of the Ancestral Pueblo from nearly the exact spot that O’Sullivan had occupied in 1873 (figs. 2 and 3).18

Adams understood the style of survey photographs to be a matter of circumstance: harsh travel conditions paired with rudimentary equipment resulting in a matter-of-fact presentation that occasionally veered toward the inspired. Yet Robin Kelsey has argued that O’Sullivan’s style was much more strategic within the context of government surveys than modernist photographers like Adams formally acknowledged.19 As Kelsey observes, the success of O’Sullivan’s images lies in his ability not only to relay a sense of the land’s grandeur but also to offer a visual metaphor for the project of nation-building that appealed to targeted audiences. For instance, O’Sullivan’s Ancient Ruins in the Cañon de Chelle featured a military survey team of four male figures nestled within and below the recess of a towering canyon wall. Though dwarfed by their physical surroundings, the men assume a stance that suggests their dominance over the land beneath their feet. Two men pose among the upper level of structures with bent knees resting on rocks; two more pose similarly among the lower structures at the base of the canyon wall. A climbing rope connects the pairs.20 In his reading, Kelsey notes how the doubling in O’Sullivan’s image constructs a before-and-after narrative that could resonate on multiple levels to support the project of westward expansion underway at the time: “The Euro-American’s exploratory penetration of the West thus appeared not only as a vigorous climb but also as an ascent associated with all the inevitability and grandeur of geologic process.”21 O’Sullivan’s depiction of Canyon de Chelly was so effective for the expansionist purposes of the 1870s that it circulated widely through multiples formats, including in two important photographic albums, which is exactly how it came to Adams’s attention several decades later.

When Adams re-created O’Sullivan’s photograph, he presumed only to respond to and refine certain formal qualities in his predecessor’s work, but his aestheticized images also work to naturalize the settler-state. In White House Ruin, Adams tightened the frame around the upper structures of the cliff dwellings, removing the lower level of dwellings that exhibit greater levels of deterioration and thus of time passed in O’Sullivan’s composition. He emptied the space of any human figures and shifted the angle of his lens to show more of the canyon wall, using a green Zeiss-Ikon G-55 filter to accentuate the natural red gradations of the rockface. These subtle changes permit the eye to glide easily between the natural beauty of the canyon wall and the extant dwellings of the Ancestral Pueblo, which appear frozen in time. White House Ruin thus serves to romanticize and historicize this Indigenous culture in service of a larger statement about the human-nature relationship. With the image, Adams encourages the viewer to look on with amazement at what is represented as the symbiotic relationship between Indigenous lifeways and nature.

In modern photographic discourse, Adams’s aestheticized image appears to stand apart from the instrumentality of O’Sullivan’s survey photograph, expressing only his personal experience at the site. In her consideration of Adams’s re-creation, Kelly Dennis notes how his image “implicitly honors and preserves the expeditionary and expansionist historical conditions of O’Sullivan’s own era both as natural and, ultimately, as irrelevant to his own aestheticized aims.”22 Dennis’s assertion that Adams’s image upholds the instrumentality of O’Sullivan’s image is precisely right; rather than separating his work from nineteenth-century photographers, the modernist aestheticization of Canyon de Chelly exemplifies how Adams reformulated the frontier lens of expedition photography for the twentieth century. In the nineteenth-century era of Westward expansion, the project of nation-building was explicit, and O’Sullivan’s images laid that process bare, encouraging political and public support for Western expansion through strategic stylistic choices. Nearly eighty years later, against mounting calls for decolonization in the postwar era, the US project of nation-building became more sublimated. Adams’s heroic aesthetic and romantic view of American wilderness perfectly overlay the settler-colonial nature of the nation’s past and present. Like O’Sullivan’s Ancient Ruins in the Cañon de Chelle, Adams’s White House Ruin is an image of conquest that plays into the nation-building efforts of his time, and the narrative it supports comes not only from the singular image but also from its contextualization within My Camera in the National Parks.

My Camera in the National Parks

White House Ruin is the eighth plate in a set of thirty photo engravings featured in My Camera in the National Parks. As a material object, the book is indebted to the albums of nineteenth-century Western survey photography that Adams collected, taking on a similar form and reproducing the sumptuous viewing experience these albums facilitate. Adams’s book is a large, spiral-bound volume measuring 14 1/2 by 12 inches. The book was co-published by Adams’s wife, Virginia, and the Boston-based publisher Houghton Mifflin. Adams, however, maintained careful control over all aspects of the project. Each image is exquisitely reproduced by H. S. Crocker Company from plates prepared by the Walter J. Mann Company, a respected photo engraver in the Bay Area.23 The images operate as singular works, featured independently on the right-hand page of each spread, opposite the image title and location, printed and centered on the left-hand page (fig. 4). By separating image from text, Adams and the book’s designer, Joseph Sinel, signaled a fine art status for the reproductions, a standing further reinforced by the book’s high price point. While Adams envisioned the growing middle-class of the postwar era as his audience, the ten-dollar price tag for My Camera in the National Parks (equivalent to just over one hundred dollars today) was nonetheless a substantial expense.24 Adams and his publisher justified the cost by suggesting, inside the book’s back dust jacket, that individual reproductions could be removed and framed as if they were original prints (hence the spiral binding).

While the images in My Camera in the National Parks hold the potential to stand alone, the book remains a consciously produced and intentionally sequenced set of images, printed and arranged in such a way as to tell a story about the nation. Adams’s grandiose aesthetic merges with the book’s material nature to encourage close, extended looking. Shifting from horizontal to vertical format and from expansive view to detailed nature study, the collection of images proceeds at a comfortable pace and rhythm, offering reader-viewers dramatic scenes of the natural world that remain serene and reassuring. The photographer chose a high-gloss Kromekote paper for the engravings, lending his scenes a luminous quality: snow-covered mountains glisten beneath bright sunlight; leaves are moist with gleaming dewdrops; and ripples shimmer across open lakes. Wide tonal range, sharp focus, and abbreviated foregrounds all serve to highlight and enhance the monumentality of geological wonders, which tend to occupy the privileged center space of Adams’s images. My Camera in the National Parks is perhaps best viewed from above as it rests on a tabletop (here, again, the spiral binding is useful). The open book fills the viewer’s field of vision and places them in an elevated position, encouraging both reverence and dominance on the part of the viewer.25

The materiality of My Camera in the National Parks and its timeless, aestheticized images echo and advance the grandness of the nation that Adams believed the parks enshrined, but the arrangement of images in the book introduces another temporal dimension. While each of his singular images presents a wilderness vista that appears at once frozen in time and timeless, the sequencing of My Camera in the National Parks frames time as linear, progressing image by image, moment by moment.26 The photographer lays this foundation in a personal statement that appears at the beginning of the book: “I begin with the primal aspects of the world, and end just where the naturalist takes over.”27 Adams’s words encourage a reading of the book as a cohesive narrative wherein time progresses with each turn of a page. This framing ultimately has implications for the individual sites featured within.

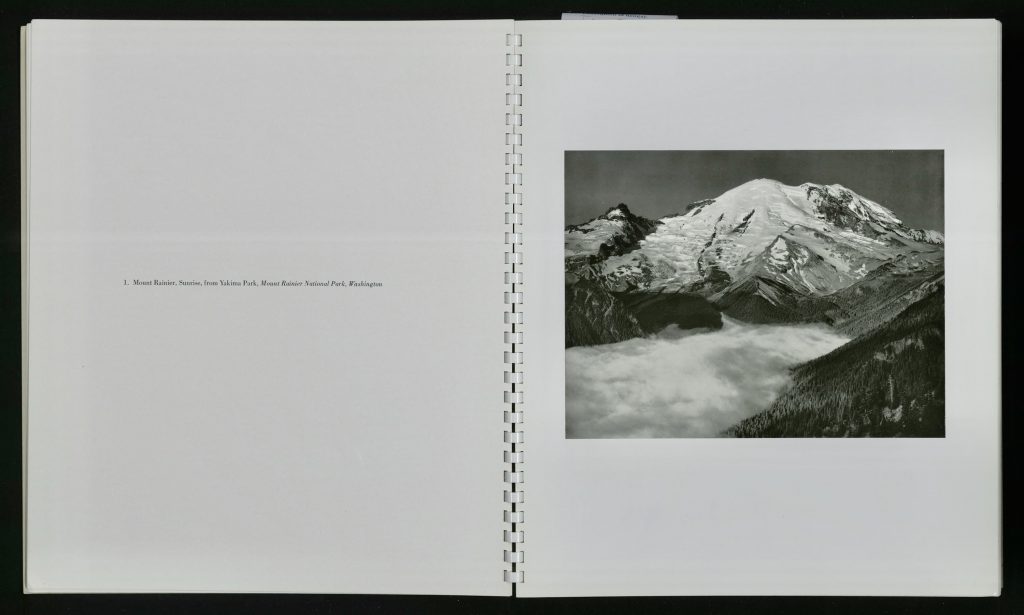

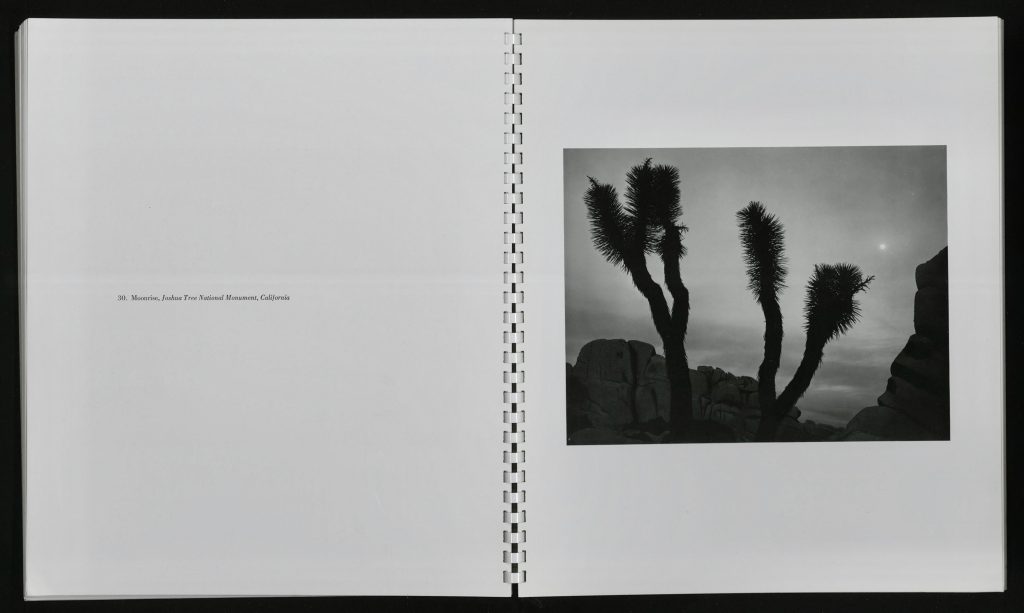

The very first plate in the book, Mount Rainier, Sunrise, from Yakima Park, Mount Rainier National Park, Washington (fig. 5), lends support to the photographer’s suggestion that his images represent the dawning of history. To capture the most dramatic and expansive views, Adams frequently hiked to higher elevations, and here the resulting image offers viewers the feeling of floating above and outside the scene, as if looking through a window onto that “primal,” bygone era that Adams describes—a feeling reinforced by the lack of human figures in the scene itself. In fact, in Mount Rainier, Sunrise, as in many other images within the book, the photographer’s own presence is effaced as much as possible through the absence or abbreviation of the foreground, leaving little indication as to where Adams may have stood. A key exception to this is the last image in the book, Moonrise, Joshua Tree National Monument, California (fig. 6), which acts as the subdued opposite of Mount Rainer, Sunrise. The image centers on the distinct form of a twisting, spiny Joshua Tree silhouetted against the dusky evening sky. Here, the perspective is one of looking up toward the bright moon in full splendor; the photographer’s feet (as well as those of the viewer) have at last found solid ground.

Adams’s image titles largely function as identifications of landmarks, but occasionally, as with the opening and closing plates, the titles include temporal references that build on the narrative Adams introduces in his opening statement. Beginning with the rising sun over Mount Rainier and ending with the rising moon over Joshua Tree, the sequence of plates in My Camera in the National Parks could be interpreted as the expanse of a day. More expressly, these bracketing images work in conjunction with Adams’s statement to encourage a reading of My Camera in the National Parks as visualizing a natural, presocial construction of the nation in tandem with the construction of the natural world. In a familiar refrain, Adams proclaims the United States as nature’s nation.

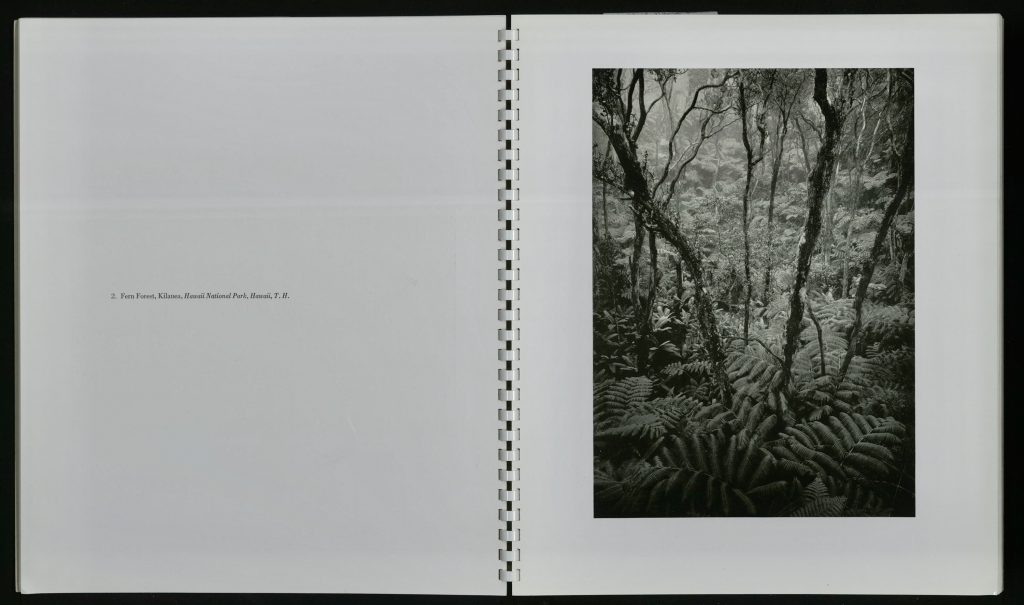

There is a small distinction here between Adams’s conception of nation-building through the parks and that implied by the National Parks Service (NPS). The original NPS mandate presumed that the parks would enshrine the land as closely as possible to its appearance at the moment of its first “discovery” by Euro-Americans working to build the nation, but Adams’s narrative within My Camera in the National Parks asserts that the nation’s formation precedes these historical actors. The various temporalities evoked through the book reflect what Mark Rifkin identifies as settler time: the “notions, narratives, and experiences of temporality that de facto normalize non-native presence, influence, and occupation” of space.28 The first three plates of the book—Mount Rainier, Sunrise (see fig. 5); Fern Forest, Kilauea, Hawaii National Park, Hawaii, T.H. (fig. 7); and Grounded Iceberg, Glacier Bay National Monument, Alaska—emphasize the nation’s elemental beginning with some of the earth’s oldest geological forms (and also with what will soon be the nation’s newest states). My Camera in the National Parks thus transports reader-viewers back to the beginning of time and nation through a sequencing of primordial landscapes that slowly invite the viewer into the fold.

In the first and only photograph in the book that provides direct evidence of human presence in the landscape, Adams represents White House Ruin as both eternal and as a site central to national formation, claiming the Indigeneity of the Ancestral Pueblos’ cliff dwellings as part of the natural and inevitable story of the United States. Although it is a re-creation of O’Sullivan’s survey image, Adams’s photograph erases the longer, violent history of white settler mapping, invasion, and occupation in the region that preceded his visit to the site, and it does little to speak to the contemporary complexity of Canyon de Chelly National Monument, which sits within and has been co-managed by the Navajo Nation since its founding in 1931. In the postwar period in which My Camera in the National Parks circulated, the Indigeneity of national park sites in states officially integrated into the Union could have been easily lost on or ignored by Adams and his readers, but it would have been harder to dismiss in relation to two other sites in the book, namely Alaska and Hawai‘i. Notably, Adams visualizes the prehistory of the nation with images of places that had yet to formally enter the Union. At the time of the book’s publication, Alaska and Hawai‘i were still only territories of the United States, and their future statehood was by no means a given. While both sites figure prominently in My Camera in the National Parks, the story of Hawai‘i’s inclusion is of particular interest, especially considering that Adams had absolutely no desire to visit the islands.

Adams in Hawai‘i

Writing to his close friend Edward Weston from the steamship Matsonia while en route to Hawai‘i in 1948, Adams confessed: “I have a hunch I will not be happy in Hawaii. . . . A great stink seems to pervade the air as we approach the Islands. . . . I am wondering if the place is as bad as I expect it to be?”29 Adams’s poor opinion of the islands was anchored in Hawai‘i’s popular image in the twentieth century, one that was in many ways antithetical to the photographer’s aesthetic sensibilities. Following the islands’ contentious annexation by the United States in 1898, aggressive advertising campaigns run by the white, settler-dominated Hawaiian Tourist Bureau and the islands’ agriculture companies depicted the islands as a tropical paradise. Bright colors played an outsize role in the visual production of the Hawaiian Islands, as did motifs of beautiful Polynesian girls, surfers, palm trees, beaches, and distant views of volcanic landmarks such as Diamond Head.30 While actual travel to the islands was accessible only to wealthy individuals (or modern artists on fellowship or commission), those who could not afford the trip were nonetheless familiar with Hawai‘i’s paradisiacal image through the constellation of tourist brochures, Hollywood films, sheet music, radio specials, nightclub acts, traveling hula troupes, and industry advertisements for pineapples, sugar, and Hawaiian shirts that circulated in American visual and popular culture throughout the twentieth century.31 Such promotional material appealed to a mainstream public, but to Adams it all gave Hawai‘i the stench of overwrought commercialism.32 What then accounts for his inclusion of the islands in his national parks project?

The postwar moment in which My Camera in the National Parks was published saw Hawai‘i taking on newfound political significance for the United States. While US colonial activity in the islands extended back decades, the attack on Pearl Harbor and the ensuing war led to increased military occupation in Hawai‘i. In the postwar years, the territory’s strategic significance only grew as the United States embraced the role of world leader and tensions with the Soviet Union rose. The militarization of the islands was masked by the colonial image of a Hawaiian paradise, but this image would not suffice for the settler colonial goal of statehood for Hawai‘i, which was increasingly at the forefront of postwar politics.33 The United States’ colonial control over Hawai‘i and a number of other overseas territories in the postwar era existed in tension with a growing anti-colonial movement. In 1945, the United Nations (UN) was established during a two-month long conference in Adams’s hometown of San Francisco, and the resulting charter included a Declaration Regarding Non-Self-Governing Territories that committed UN members to supporting the development of self-government in territories under their colonial possession. This declaration and international criticism put pressure on the United States to reevaluate its relationship with its territories. Rather than move toward decolonization, however, the topic of statehood for Hawai‘i drove political and public debate.

The first postwar bill for Hawaiian statehood appeared before Congress in 1947, just a year before Adams’s Guggenheim-funded travel to the islands. While Hawai‘i held enormous strategic value for the United States in the Cold War era, the bill would stall in the Senate, and the Hawaiian statehood campaign would proceed slowly throughout the next decade. Congress continuously rejected statehood bills, citing concern for the Territory’s inchoate character—a thin veil for racism toward Hawai‘i’s largely Asian American population who, like the islands’ Indigenous community, remained disenfranchised under territorial rule. Anti-statehood efforts on the part of Kānaka Maoli (Native Hawaiians) who opposed the continued settler domination of their lands by both White Americans and Asian Americans took various forms, but they were largely ignored. At the start of the statehood campaign, the Kanaka Maoli concept of aloha was instead subverted in media coverage on the issue to suggest that Hawai‘i’s Indigenous population welcomed statehood.34 The growing national and political discourse around the territory seems to have left a mark on Adams, who added it to his revamped national parks project, even as his letters suggest he did so somewhat begrudgingly. In ways both conscious and unconscious, Adams engaged the colonial discourse surrounding the islands and ultimately advanced the settler agenda of statehood by incorporating Hawai‘i into the imagined national landscape of his book.

When the photographer first arrived in Honolulu in April 1948, the island of O‘ahu seemed to offer little of interest to his creative and colonial eye, and he could not resist comparing Hawai‘i unfavorably to the landscapes back home. Adams registered the difference between Hawai‘i and Northern California through Western values of authenticity, ideal beauty, and order. In letters to friends and family, Adams noted his initial frustration with the technical challenges created by the tropical climate, where heat, humidity, frequent rain, and high trade winds complicated the photographer’s physically rigorous outings.35 In his preoccupation with the perceived inadequacy of the islands’ environment, he expressed a longing for “pine needles, hard granite, clear water, and DRY air!”36 He complained of the volcanic islands’ “feeble” rock formations and yearned for “a little piece of granite just to remind me the world is solid!”37 It is hard to ignore such commentary’s roots in a colonial discourse that linked culture and environment in order to build hierarchies of people and places.38 His preference for “DRY air” and “hard granite” over “feeble rock” carry connotations that position the continental United States as masculine, strong, stable, and superior to the islands, which have historically figured as feminine and fragile in colonial depictions.

Adams’s feelings toward Hawai‘i would settle a bit within the boundaries of Hawaii National Park, which originally spanned tracts of land outside commercial districts on the Island of Mau’i and the Island of Hawai‘i.39 In the open spaces of the park, he could assimilate the islands into the ideas of wilderness and natural/national creation guiding his project. Looking out over the Pacific Ocean from Haleakalā, he produced a stunning image of the snow-capped peaks of Mauna Kea and Mauna Loa on the nearby islands of Mau’i, but this classic Adams-style image does not appear in his book.40 Rather, the photographer’s initial unease with Hawai‘i seems to register in the un-Adams-like images from Hawaii National Park that appear in My Camera in the National Parks. In Fern Forest, Kilauea, for example, there is no grand, central landmark to grab the eye, no sweeping vista to take the breath away (see fig. 7). Adams instead created an image that depicts Hawai‘i as frenzied and impenetrable, with rhizomatic fronds covering the foreground plane and extending upward in the near distance. Thin, spiny branches reach out toward the viewer from the foreground, creating a barrier to the larger forest beyond. Elsewhere in the book, Adams offers a comparable view of an inviting, sylvan forest from Beartrack Cove in Alaska, emphasizing how his depiction of Hawai‘i forecloses the space from the viewer.

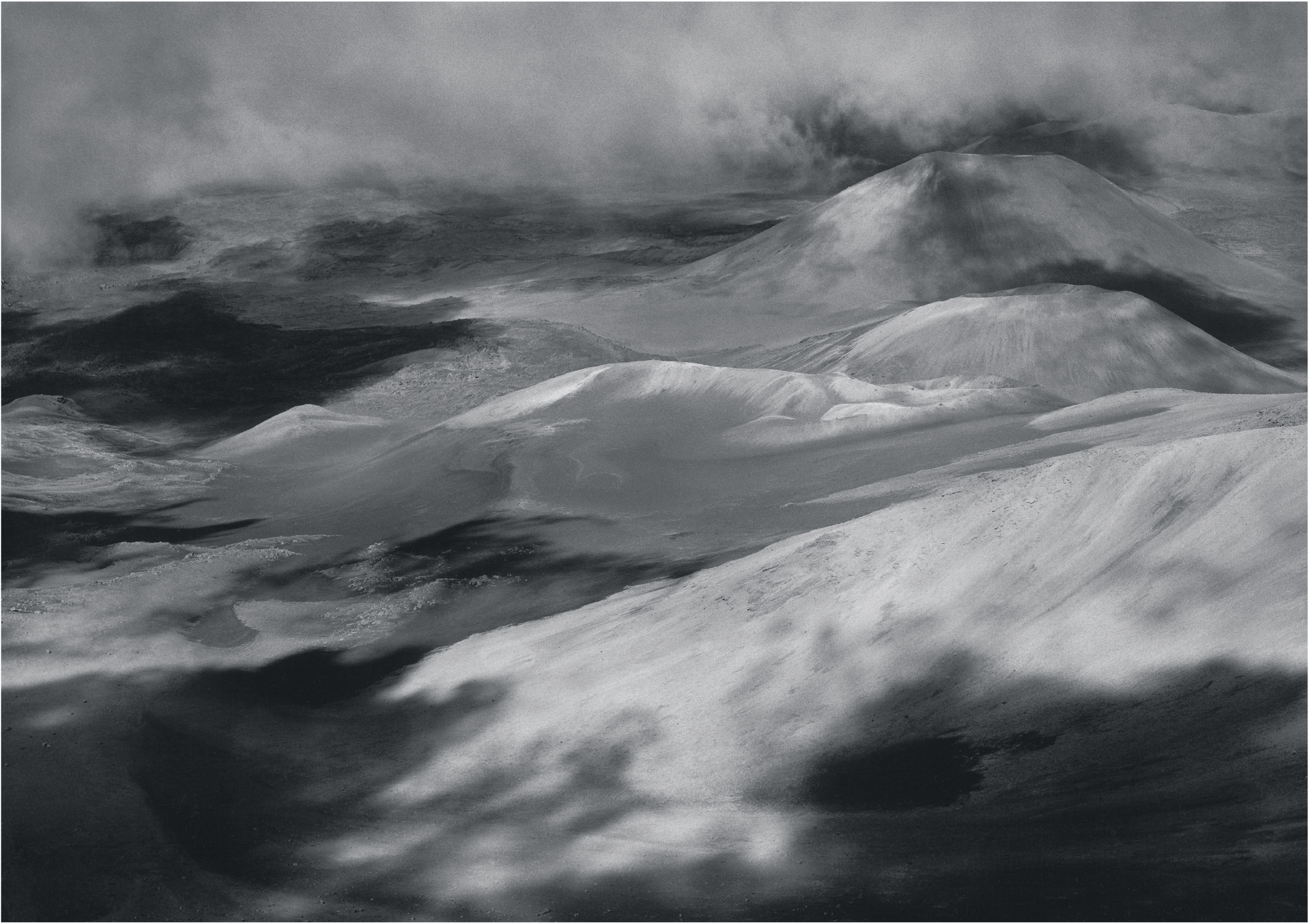

A second photograph from Hawaii National Park, entitled The Crater of Haleakala, Clouds, Hawaii National Park, Maui, T.H., is similarly uncharacteristic of the photographer (fig. 8). Directing his 5 x 7 Linhoff camera at a downward angle into the crater, the photographer eliminated any presence of an anchoring horizon line. A light band of hazy clouds at the top of the frame obscures the background view and casts dark, amorphous shadows on the crater floor. The internal bands of cloud and shadow along the top and bottom of the frame flatten the pictorial space and squeeze the most defined aspects of the landscape into the middle of the photograph. Even here, the subtle valleys and smooth ridges of the crater interior, a natural depression at the volcano’s summit caused by collapse and erosion, are difficult to discern. Whereas Adams’s conventional approach to the natural scene is characterized by breathtaking, awe-inspiring views, his diffuse depictions of Kīlauea and Haleakalā are disorienting by comparison.

Fern Forest and Haleakala, Clouds raise some tension in Adams’s narrative of an American nation that preexisted colonialism. Indeed, some of the photographer’s own hesitancy to integrate Hawai‘i into the American natural scene is evident in the way he included the abbreviation “T.H.” for the Territory of Hawai‘i in his image titles. No such indication appears for his images from Alaska, even though it too was a US territory at the time of the book’s publication. Yet, the narrative arc these images help to foster in relation to others featured in the book work to resolve some of that tension. For instance, if we read Haleakala, Clouds, which appears as the twenty-sixth plate, as a counterpart to the book’s opening volcanic scene in Mount Rainer, Sunrise, the temporal narrative proceeds from an active volcanic site to a dormant one; that is, from a nation in formation to a nation formed and habitable. The proximity Adams achieved at Haleakalā—photographing right from the crater’s edge, where the park’s welcome center had recently been built—signals its inactivity and safety.

Adams’s decision to add Hawai‘i to his Guggenheim-funded travels, and his inclusion of Hawaii National Park within the pages of My Camera in the National Parks, was an assertion of the islands’ American status at a moment when their future was in question. His photographs from Hawai‘i depart from the popular image of the islands, but they nonetheless carry forth the colonial discourse that frames Hawai‘i as mysterious yet non-threatening. The images he features from Hawaii National Park also depart from his signature aesthetic, but within the context of the book, the visual tensions of the Hawai‘i images are subdued; Mount Rainier and Haleakalā are mapped as a unified nation, their spatial distance collapsed into the turn of just a few pages. Positioning his images of Hawai‘i throughout the checklist of My Camera in the National Parks, from its earliest pages to its last, Adams stakes a temporal claim to Hawai‘i as well, integrating the islands into the imagined national landscape of the United States as always already American.

New Frontiers

Six years before his trip across the Pacific Ocean for My Camera in the National Parks, Adams wrote in a press release for his MoMA exhibition on nineteenth-century photography that “the ‘Frontier’ is not limited by any specific boundary of time.” Recalling the various projects of O’Sullivan, William Henry Jackson, and others on view in the exhibition, he noted that, “New territories made new problems, new problems required new solutions.”41 In the wake of the Second World War, Adams took it upon himself to continue this patriotic problem-solving. The United States moved into the role of global superpower yet wrestled with internal contradictions to its democratic image, as social inequalities persisted and the nation continued its colonial domination of overseas territories. Adams offered a solution, taking up the same nation-building goals as his nineteenth-century forebears, albeit under the guise of individual creative expression and conservation advocacy. It was wildly effective, for the photographer’s career as well as the nation. Adams’s reputation grew during the Cold War era as he provided a seemingly natural foundation for the nation’s self-appointed role as leader of the free world.

Adams’s vision of the natural scene reflected a larger vision of American society. The photographer depicted the American wilderness as vast, powerful, and noble—qualities that appear inherent to the nation itself through his images. The images included in My Camera in the National Parks offer a chorus of triumphant national landscapes, but more than simply reflecting the nation’s strength or Adams’s unique perspective on it, the book actively constructs the settler nation along particular orders of time and space. Even as My Camera in the National Parks presumes a seamless and natural origin story for America, the story of the book’s production—from its origins in a DOI commission, to its recycling of frontier myths, to Adams’s uncomfortable travels in Hawai‘i—reveals the difficult work at the heart of the settler colonial process, where tensions and contradictions are constantly in need of suppression, and the right of possession is constantly in need of assertion.

While My Camera in the National Parks encourages a specific reading of Adams’s images as representing a unified and stable American landscape, the adaptable design of the book adds some complexity to the analysis. As previously noted, the spiral binding of the book was intended to allow consumers the option of removing a page so that a given image might be framed and displayed on the wall as if it were an original print. When images are removed from My Camera in the National Parks, their untethered context—and, in the case of Adams’s images of Hawai‘i, their ambiguous, anomalous aesthetic—opens some space for the configuration of entirely new geographies and the creation of entirely new meanings in a process of (re)mapping that, as Seneca scholar Mishuana Goeman argues, holds the potential to “unsettle” seemingly fixed settler notions of place.42 There are limitations, however. Once Adams’s images are displayed as “art” in the way he envisioned, they become further contained and fixed, not only materially—within a picture frame—but also ideologically, within a Western framework that produces the photograph, the land, and the view as an object of possession: my camera.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful for the support and valuable feedback on this article provided by Monica Bravo, Emily Voelker, and the editorial team at Panorama. I also want to thank Jessica Landau for reviewing an early draft and encouraging this project along the way.

Cite this article: Lauren Johnson, “Reading and Re-Reading Ansel Adams’s My Camera in the National Parks,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 6, no. 2 (Fall 2020), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.10873.

PDF: Johnson, Reading and Re-Reading Ansel Adams

Notes

- For an expanded discussion of how Adams’s signature style developed in the context of this project and how it is represented in The Teton Range and the Snake River, see Rebecca A. Senf, Making a Photographer: The Early Work of Ansel Adams (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press; Tucson: Center for Creative Photography at the University of Arizona, Tucson, 2020), 199–207. ↵

- Ansel Adams, “The Meaning of the National Parks,” My Camera in the National Parks (Yosemite National Park, CA: Virginia Adams; Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1950). Cécile Whiting uses the term “moral sublime” to identify how Adams’s postwar landscapes offer both comfort and a call for protection. See Whiting, “The Sublime and The Banal in Postwar Photography of the American West,” American Art 27, no. 2 (Summer 2013): 47. ↵

- Deborah Bright discusses the significance of Adams and the resurgence of the landscape genre in the postwar era in two important essays: Bright, “Of Mother Nature and Marlboro Man: An Inquiry into the Cultural Meanings of Landscape Photography,” in The Contest of Meaning: Alternative Histories of Photography, ed. Richard Bolton (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1987); Bright, “Victory Gardens: The Public Landscape of Postwar America,” Views (Spring 1990). Both essays are available online: http://www.deborahbright.net. ↵

- As reported in the San Francisco Chronicle, five thousand copies of My Camera in the National Parks were printed and signed by Adams. Senf, Making a Photographer, 258n61. ↵

- Senf’s recent study, Making a Photographer, engages most fully with Adams’s publishing endeavors, serial photo projects, and photobooks. While she addresses My Camera in the National Parks in the context of Adams’s stylistic development, she does not offer a sustained analysis of the book itself. ↵

- For more on settler colonialism as an act of erasure, see Patrick Wolfe, The Settler Complex: Recuperating Binarism in Colonial Studies, edited by Patrick Wolfe (Los Angeles: UCLA American Indian Studies Center, 2016). For more on how this erasure is carried forth through government policy and popular culture, see Mishuana Goeman, Mark My Words: Native Women Mapping Our Nations (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013) and Philip J. Deloria, Playing Indian (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998). ↵

- For critical histories of the early national parks, see Rebecca Solnit, Savage Dreams: A Journey into the Hidden Wars of the American West (San Francisco: Sierra Club Books, 1994) and Richard Grusin, Culture, Technology, and the Creation of America’s National Parks (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004). ↵

- Margaret Grebowicz, The National Park to Come (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2015), 42. ↵

- Aileen Moreton-Robinson, The White Possessive: Property, Power, and Indigenous Sovereignty (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2015), xx–xxi. For more on photography and whiteness in the national parks, see Martin Berger, “Landscape Photography and the White Gaze” in Sight Unseen: Whiteness and American Visual Culture (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005). ↵

- Adams worked for the DOI between October 1941 and June 1942, producing approximately 220 prints for the agency. While the collection reflects the mural project’s eventual focus on the national parks, it also includes studies of Boulder Dam, portraits of Navajo (Diné) and Pueblo Indian people, and photographs of architecture and cultural practices from Southwestern pueblos. Interested readers can browse the collection on the National Archives website: https://catalog.archives.gov/id/519830. ↵

- Ansel Adams to E. K. Burlew, First Assistant Secretary, Department of the Interior, December 28, 1941. Official Personnel File of Ansel E. Adams, The National Archives, accessed July 9, 2020, https://catalog.archives.gov/id/7582466. ↵

- Ansel Adams to A. E. Demaray, Associate Director, National Parks Service, June 20, 1942. Official Personnel File of Ansel E. Adams, The National Archives, accessed July 9, 2020, https://catalog.archives.gov/id/7582466. ↵

- Adams’s letters to and from Nancy Newhall, written between March and May of 1948 while he was working on My Camera in the National Parks, reveal a particular concern for the accusations against the Photo League. See, for example, Ansel Adams to Nancy Newhall, March 23, 1948, and Ansel Adams to Nancy Newhall, May 12, 1948. Ansel Adams Archive, Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona, Tucson. Hereafter, AAA–CCP. ↵

- Ansel Adams to Walter Winchell, October 2, 1950. AAA–CCP. Emphasis in the original. ↵

- For a detailed timeline of events related to Japanese internment and Executive Order 9066, see Brian Niiya, ed., Densho Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.densho.org/timeline/. ↵

- Elena Tajima Creef, Imaging Japanese America: The Visual Construction of Citizenship, Nation, and the Body (New York: New York University Press, 2004), 41. ↵

- The exhibition Photographs of the Civil War and the American Frontier was on view at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City March 3–April 5, 1942. A press release, checklist, and installation views for the exhibition are available online: https://www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/3031?locale=en. ↵

- Ansel Adams to Beaumont and Nancy Newhall, October 26, 1941, in Ansel Adams: Letters, 1916–1984, ed. by Mary Street Alinder and Andrea Gray Stillman (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 2001), 136. ↵

- Robin Kelsey, Archive Style: Photographs and Illustrations for U.S. Surveys, 1850–1890 (Berkley: University of California Press, 2007), 3. ↵

- The figures in O’Sullivan’s Ancient Ruins in the Cañon de Chelle are difficult to see in regular reproductions, but zoomable reproductions of the image are available via Google Arts & Culture. The digitized print from the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston offers a reproduction of the image as Adams may have viewed it in a nineteenth-century album: https://artsandculture.google.com/asset/ancient-ruins-in-the-caon-de-chelle-nm-territory/QQGVNG9qN8YkPQ. ↵

- Kelsey, Archive Style, 108. ↵

- Kelly Dennis, “Eclipsing Aestheticism: Western Landscape Photography After Ansel Adams,” Miranda 11 (2015): 28, https://doi.org/10.4000/miranda.6920. ↵

- For more on the importance of print quality to Adams, see Senf, 258–59n67. ↵

- CPI Inflation Calculator, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, accessed October 20, 2020, https://www.bls.gov/data/inflation_calculator.htm. ↵

- Elizabeth Hutchinson offers a similar reading of nineteenth-century photo albums. See Hutchinson, “They Might Be Giants: Galen Clark, Carleton Watkins, and the Big Tree,” in A Keener Perception: Ecocritical Studies in American Art History, edited by Alan C. Braddock and Christoph Irmscher (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2009), 115. ↵

- The temporal implications of wilderness are one of William Cronon’s major critiques of the concept. See Cronon “The Trouble with Wilderness: Or, Getting Back to the Wrong Nature,” in Uncommon Ground: Rethinking the Human Place in Nature, edited by William Cronon (New York: W. W. Norton & Co., 1995): 76–79. ↵

- Adams, “A Personal Statement,” in My Camera in the National Parks. ↵

- Mark Rifkin, Beyond Settler Time: Temporal Sovereignty and Indigenous Self-Determination (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2017), 9. ↵

- Ansel Adams to Edward Weston, April 10–14, 1948, in Ansel Adams: Letters, 199. ↵

- DeSoto Brown, “Beautiful, Romantic Hawaii: How the Fantasy Image Came to Be,” The Journal of Decorative and Propaganda Arts 20 (1994): 252–71. ↵

- Prior to Adams’s project in Hawai’i, the photographer Edward Steichen and the painter Georgia O’Keeffe also completed notable commissions in Hawai’i for Matson Cruise Line and Dole Pineapple Company, respectively. See Patricia A. Johnston, “Advertising Paradise: Hawai’i in Art, Anthropology, and Commercial Photography,” in Colonialist Photography: Imag(in)ing Race and Place, ed. Eleanor M. Hight et al. (London and New York: Routledge, 2002), 188–91, and Sascha Scott, “Georgia O’Keeffe’s Hawai’i?: Decolonizing the History of American Modernism,” American Art 34, no. 2 (Summer 2020): 27–53. ↵

- Understanding how Adams responds to and, as I argue in this article, contributes to the visual culture of Hawai’i helps address the cultural imperialism within the field of American art history that Stacy Kamehiro identifies in her recent article in this journal: Stacy L. Kamehiro “Empire and US Art History from an Oceanic Visual Studies Perspective,” Bully Pulpit, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 6, no. 1 (Spring 2020), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.10072. ↵

- Teresia K. Teaiwa, “bikinis and other s/pacific n/oceans,” The Contemporary Pacific 6, no. 1 (Spring 1994): 87. ↵

- For a more detailed account of Congressional statehood debates throughout the long 1950s, see Roger Bell, Last Among Equals: Hawaiian Statehood and American Politics (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1984). For a more critical history of statehood efforts, see Dean Itsuji Saranillio, Unsustainable Empire: Alternative Histories of Hawai’i Statehood (Durham: Duke University Press, 2018). ↵

- Adams to Virginia Adams, April 1948, in Ansel Adams: Letters and Images, 200. ↵

- Adams to Nancy Newhall, May 6, 1948. Beaumont and Nancy Newhall Archive, Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona, Tucson. Hereafter, BNN-CCP. ↵

- Adams to George, Betty, and Nancy Newhall, May 8, 1948. BNN-CCP. ↵

- Gary Y. Okihiro, Pineapple Culture: A History of The Tropical and Temperate Zones (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2010). ↵

- Hawaii National Park was separated into two distinct parks in 1961 with Hawai’i Volcanoes National Park on the island of Hawai’i and Haleakalā National Park on the island of Mau’i. ↵

- This image, entitled Mauna Kea and Mauna Loa on the Island of Hawaii, from Haleakala, in Hawaii National Park, Maui, can be viewed in the online collections of the Center for Creative Photography at the University of Arizona, Tucson: http://ccp-emuseum.catnet.arizona.edu/view/objects/asitem/search@swg’85.122.56′,’true’/0?t:state:flow=09dfb141-7ac1-4212-8253-d145e8ea9151. ↵

- Ansel Adams quoted in “Museum of Modern Art Opens Exhibition of Photographs of the Civil War and the American Frontier,” press release, February 26, 1942. Museum of Modern Art Exhibition History Online Archives, accessed July 9, 2020, https://www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/3031?locale=en. ↵

- Goeman, Mark My Words, 3. ↵

About the Author(s): Lauren Johnson is Assistant Professor of Art History at Moreno Valley College