Siŋté Máza (Iron Tail)’s Photographic Opportunities: The Transit of Lakȟóta Performance and Arts

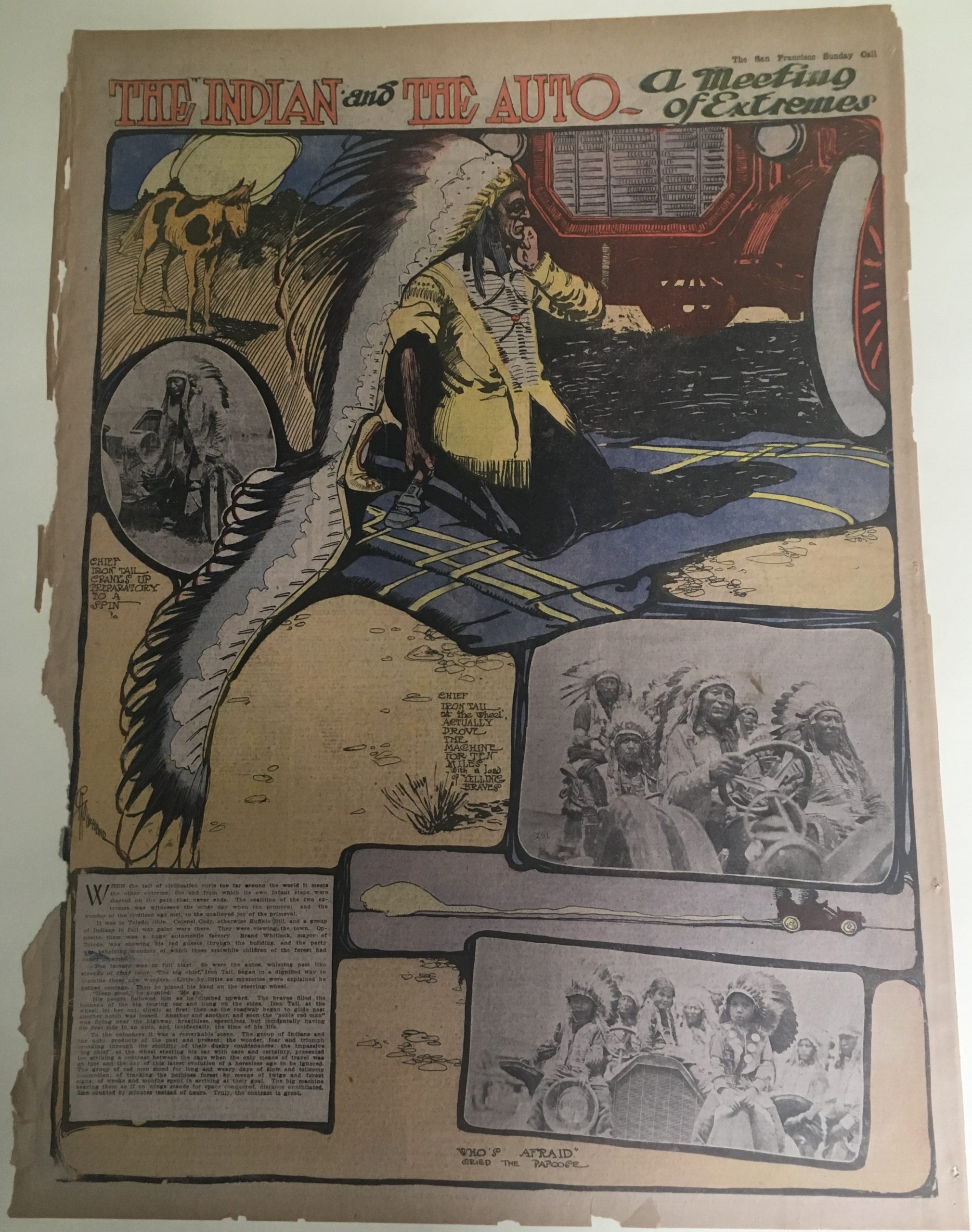

In 1907, the San Francisco Call printed a full-page collage that evocatively mingles drawings, half-tone photographs, and text to present “The Indian and the Auto: A Meeting of Extremes” (fig. 1). Implying an uneasy clash of old and new, a large central sketch depicts an Indian figure sitting on a blanket wearing a war bonnet and trailer, facing the front grate of an automobile.1 His chin rests meditatively in one hand, and he holds a wrench, with his sleeve rolled up in anticipation of work. The scene implies that the horse, seen in the background, has been rendered obsolete. While this figure is not captioned, the photographs reproduced around the drawing represent Siŋté Máza (Iron Tail, c. 1840s–1916), a longtime Lakȟóta “chief” in Buffalo Bill’s Wild West who appeared frequently in early twentieth-century mass media. In the oval photograph to the left, Siŋté Máza leans against the hood of the car wearing regalia, cranking the handle to start the vehicle’s engine. At right, a photographic silhouette of Siŋté Máza in the driver’s seat is reproduced with a note that he “actually drove the machine for ten miles with a load of yelling braves.” The text expands on the ensuing test drive at a Toledo, Ohio, automobile factory: “Soon the ‘noble red man’ was flying over the highway, breathless, speechless, but incidentally having his first ride in an auto, and, incidentally, the time of his life.” Popular photographic technology of the era was unable to capture such rapid motion, and the event is rendered with a drawing in a long horizontal box, imagining the car speeding across the landscape with a trailing cloud of dust. The bottom photograph implies the future, with three children seated on the hood of the car with the confident caption, “Who’s Afraid cried the Papoose.” From the horse to the children, the image builds a trajectory that imagined Indians’ slow but inevitable embrace of technology, and, by subtext, civilization. Its text reinforces this moment “when the primeval and the wonder of the civilized age met, to the unalloyed joy of the primeval,” and clarifies the opposition at work between “the group of Indians and the auto, products of the past and present.” Developing the metaphor, the text reads, “The group of red men stood for the long and weary days of slow and toilsome locomotion. . . . The big machine bearing them as if on wings stands for space conquered, distance annihilated, time counted by minutes instead of hours.”2

These constructed polarities of past and present, of slow and fast, and of immobility and mobility underscore common constructions of Indians in early twentieth-century US culture. As Phillip J. Deloria argues in Indians in Unexpected Places, such juxtapositions of the so-called primitive Indian with modernity rest on racist beliefs frequently held in non-Native US settler communities of stagnant and unchanging Indian culture.3 The drawings, photographs, and text operate in tandem to meet these fantasies and ignore the undergirding mobilities of the photographs—made in Ohio and printed in California—and of the performers themselves, who mainly came from the Lakȟóta nation and had traveled not only around the United States but also through Europe. The collage effect of round and square images with drawn frames build the page as a family album, a scrapbook of Siŋté Máza’s technological adventures as a microcosm of Indians’ encounters with modernity. While this visual structure infers a typical non-Native, middle-class identity, this is not a scrapbook of Siŋté Máza’s own devising.4 Stereotypes of Indian identity, represented by clothing and a presumed lack of familiarity with modernity, are traits that Anishinaabe scholar Gerald Vizenor critiques as the presumptions of “manifest manners,” racist underpinnings that justify the logic of manifest destiny.5 Yet Siŋté Máza’s life and frequent intersections with photography as a professional performer for about twenty-five years with Buffalo Bill’s Wild West challenge the conceit of his stagnation.

The likelihood that the 1907 automobile ride documented by the San Francisco Call was Siŋté Máza’s first is slim. It has been difficult to establish even basic facts about his life. His birth year has been published as ranging between 1842 and 1850, and census records list it between 1857 and 1861.6 He seems to have been married twice, to Waŋbli Wašté (Pretty Eagle) and later to Tȟašûŋke Lúta (Red Horse; born c. 1856). He had at least four children, one of whom, Philip Siŋté Máza (Phillip Iron Tail, c. 1879/80–1904), studied at Carlisle Indian Industrial School from 1892 to 1898, became a Wild West performer, and tragically died in a train collision in 1904.7 The first documented mention of Siŋté Máza’s Wild West performance is in 1897, though he appears in photographs throughout an album generally linked to the World’s Columbian Exposition in 1893.8 Press stories and subsequent scholars have hailed Siŋté Máza as a negotiator in a Lakȟóta diplomatic delegation to Washington, DC, in 1872, and a warrior fighting at Greasy Grass (Little Bighorn) and at Wounded Knee, but I have not been able to corroborate these claims.9 More likely is the description by Major Israel McCreight (1865–1958), whom William F. Cody (1846–1917) and Siŋté Máza frequently visited (traveling by automobile) at his Pennsylvania home, which McCreight dubbed “the Wigwam.” McCreight wrote, “Iron Tail was not a war chief and had no remarkable record as a fighter; he was not a ‘medicine’ man or conjurer.”10 He probably became famous not from actual battles but through the Wild West show’s marketing, which billed him as a celebrity performer. Mass-media articles frequently named him “Chief Iron Tail” or, in French, “Chef Queue-de-fer” as they traced the travels of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West.11 Siŋté Máza’s notoriety expanded when he was featured as one of James Earle Fraser’s (1876–1953) three models for the Indian head, or buffalo, nickel, in 1913, which remained in circulation until 1938.12 As a celebrity performer, Siŋté Máza visited hundreds of national and international destinations between 1893 and 1916, and it is likely that he often traveled by automobile.13

An image industry of both formal and ludic representations built a myth of Siŋté Máza in a variety of media, from posters to sculpture to ledger-style drawings, but photographs are the most common medium in which he appears. In most images, he wears Lakȟóta regalia, which was requisite for Wild West performance and reinforced non-Native assumptions that all Indians were Plains Indians.14 A superficial reading of such photographs might stress the medium’s frequent complicity with the settler gaze; billed as a stand-in for all Native Americans, such images might be seen to freeze Siŋté Máza as an exotic Other for popular entertainment or within projects of salvage ethnography.15 Small-scale, collectible images of Siŋté Máza, such as nickels and postcards, could be interpreted as making him or his image available for possession as an icon of a dying race.16 However, as Christopher Pinney has argued, “photography can be used to position bodies and faces within history, and it can also be used as a means of escape.”17 Therefore, as this essay proposes, such representations can be read against the grain, as objects that disrupt stereotypes rather than reinforce domination and erasure.

A close analysis of three sets of photographs of Siŋté Máza—spanning 1898 and 1908 and following his travels from New York to Rome to Cody, Wyoming—interprets his use of what I refer to as photographic opportunities to deflect being pigeonholed as only an archetypal Indian. The concept of photographic opportunity underscores Siŋté Máza’s possibilities of agency through his often overt interaction with the mechanisms of his representation. Anthropologist Linda Scarangella McNenly has framed a moderated definition of agency in contexts of asymmetrical power relations in her analysis of Wild West performers. She asks: “Have Wild West shows provided Native performers a space to experience and express their own social meanings of Nativeness?”18 While certainly “embedded in a complex web of (unequal power) relationships with show entrepreneurs, government agents, and the public,” she affirms that Native performers “found ways to use this encounter for their benefit and to experience identity in their own ways,” thus leaving room for the possibility of agency by social actors beyond solely the reproduction of structure.”19 She builds a qualified space for agency within a constricting system, noting as well that “agency is not necessarily equated with resistance.”20 Reading Siŋté Máza’s interventions in image-making is tricky because almost no primary textual sources squarely report his perspectives on his world; as Kate Flint has observed, press reports, like the many that built mythologies around Siŋté Máza, are full of “spin-doctoring.”21 Furthermore, Cody insisted that Buffalo Bill’s Wild West, in which Siŋté Máza performed, offered viewers a “true picture of American frontier life with real characters,” and many observers elided differences between performances onstage and the performers’ lives off stage.22 For example, the New York Times claimed in April 1901 that “the Indian of the show is very little different behind the scenes from what he is before the curtain.”23 Siŋté Máza pushed past that conflation, playing with the slippages between self and performed identity as he underscored a relational existence.

In other media in which Siŋté Máza’s visage appears, such as posters, sculptures, and paintings, he seems to have had less control over his image, but his interactions with photographers and experiments with pose, props, and clothing suggest his self-conscious and complex relationship with image-making. The resulting photographs and stories around them suggest his role as collaborator with photographers.24 Clothing in particular operates as a signifier of his various relationships, with the Lakȟóta nation, with settler society, with a community of traveling performers, and, more distantly, with Cree culture. Photographs also suggest the diverse networks in which he circulated; he appears in non-Native formal dining rooms and in snapshots swimming in the surf with other Lakȟóta performers and cowboy performer Johnny Baker (1869–1931) and his family in Santa Barbara, California.25 The array of photographs refuse to participate in easy dialectics between Indigeneity and modernity; in his co-production of images, Siŋté Máza asserts that Native and modern are not incompatible categories.26

By using photography to present multiple personas and reveal his mobility, both literally and metaphorically, Siŋté Máza defies the constraints of singular identity. Instead, he constructed his public persona through the theme of transit. By being unfixed and non-static, he was never fully knowable, through photographs or otherwise. In The Transit of Empire: Indigenous Critiques of Colonialism, Jodi A. Byrd suggests opposing operations of transit in both building and challenging power structures. On the one hand, non-Natives embrace the archetype of the Indian as a vague metaphor; she argues that “the United States deploys a paradigmatic Indianness to facilitate its imperial desires.”27 At the same time, as Byrd asserts, “‘Indian,’ at least in the context of the United States, can be seen simultaneously as an empty referent . . . and as overdetermined and therefore carrying multiple significations that stretch and silhouette the real within the planetary parallax of imperialism.”28 Byrd explores both confining structures and liberating possibilities through the transit of the Indian. In the context of circular colonialist views of Indianness, a recognizable figure like Siŋté Máza used his mobility and repeated figuring in images to intervene in these constructions. Drawing on Vizenor’s ideas of transmotion and survivance, Byrd observes: “To be in transit is to be an active presence in a world of relational movements and countermovements. To be in transit is to exist relationally, multiply.”29 This essay proposes that Siŋté Máza used photographic opportunities to emphasize transit and relationality; the Lakȟóta performer leveraged photography’s strategies and spaces to construct his own identities in dialogue with and in challenge to the identity imposed upon him.

The production of these images coincided with US government attempts to quell the Lakȟóta nation after the conclusion of the so-called Sioux Wars with the Massacre at Wounded Knee in 1890 and the establishment and enforcement of reservations. In the following decades, assimilation policies encouraged Lakȟótas to discard their cultural markers and embrace US citizenship and culture.30 As a Lakȟóta man working as a professional performer against the backdrop of settler colonial attempts to erase his community, Siŋté Máza both merged himself with the archetype of an American Indian as aged warrior wearing a war bonnet and also showed himself as adapted to non-Native culture. His insistent and repeated presence as a modern Lakȟóta man, as well as his interventions in acts of representation, subtly work against constructions of erasure and exoticism, during his life and today. My analysis of this material reinforces the call from Tuscarora scholar Jolene Rickard for studies that not only consider representations of the victimization of Native Americans but also “strategies that they have used to maintain their world-view.”31 In exploring “visual sovereignty,” as Rickard has argued elsewhere, scholars might interpret “the interconnected space of the colonial gaze, deconstruction of the colonizing image or text, and Indigeneity.”32 As represented by the many photographs for which he posed, images of Siŋté Máza underscore the challenges he faced as part of a subjugated community and how he navigated the contradictions of finding financial and geographical mobility by reenacting the defeat of Lakȟótas in the face of US expansion to the west in Wild West performance. Reading the images in the context of their relational production, circulation, and use of material culture, I will ask how Siŋté Máza, when posing for photographs, created opportunities to demonstrate his agency, authority, and modernity as he constructed his own mythology by working both with and against non-Native expectations of Indianness.

New York, 1898

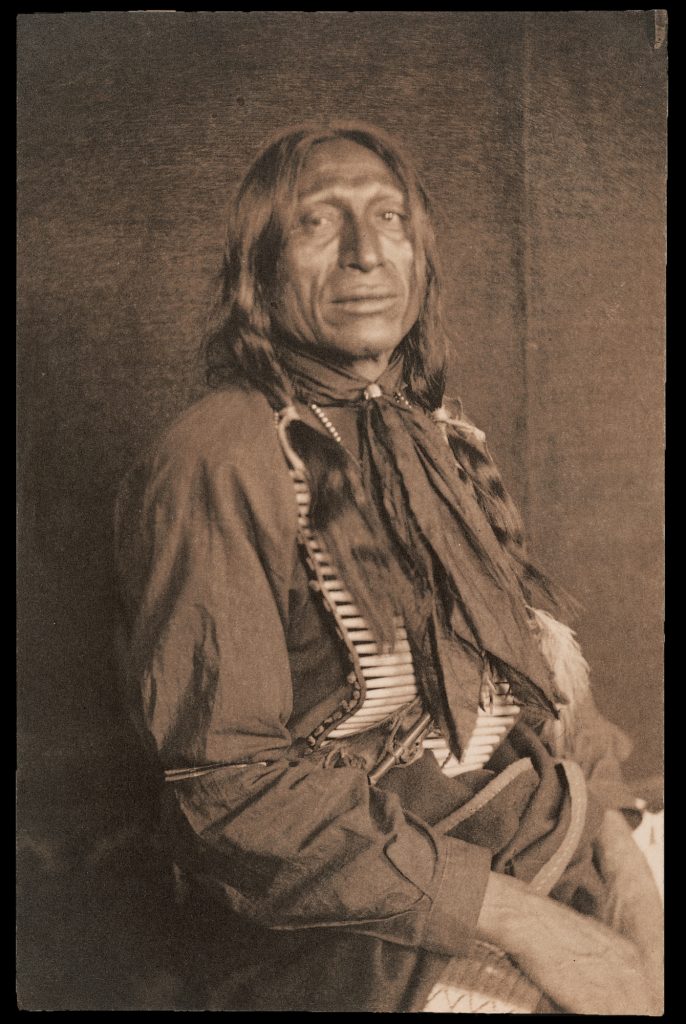

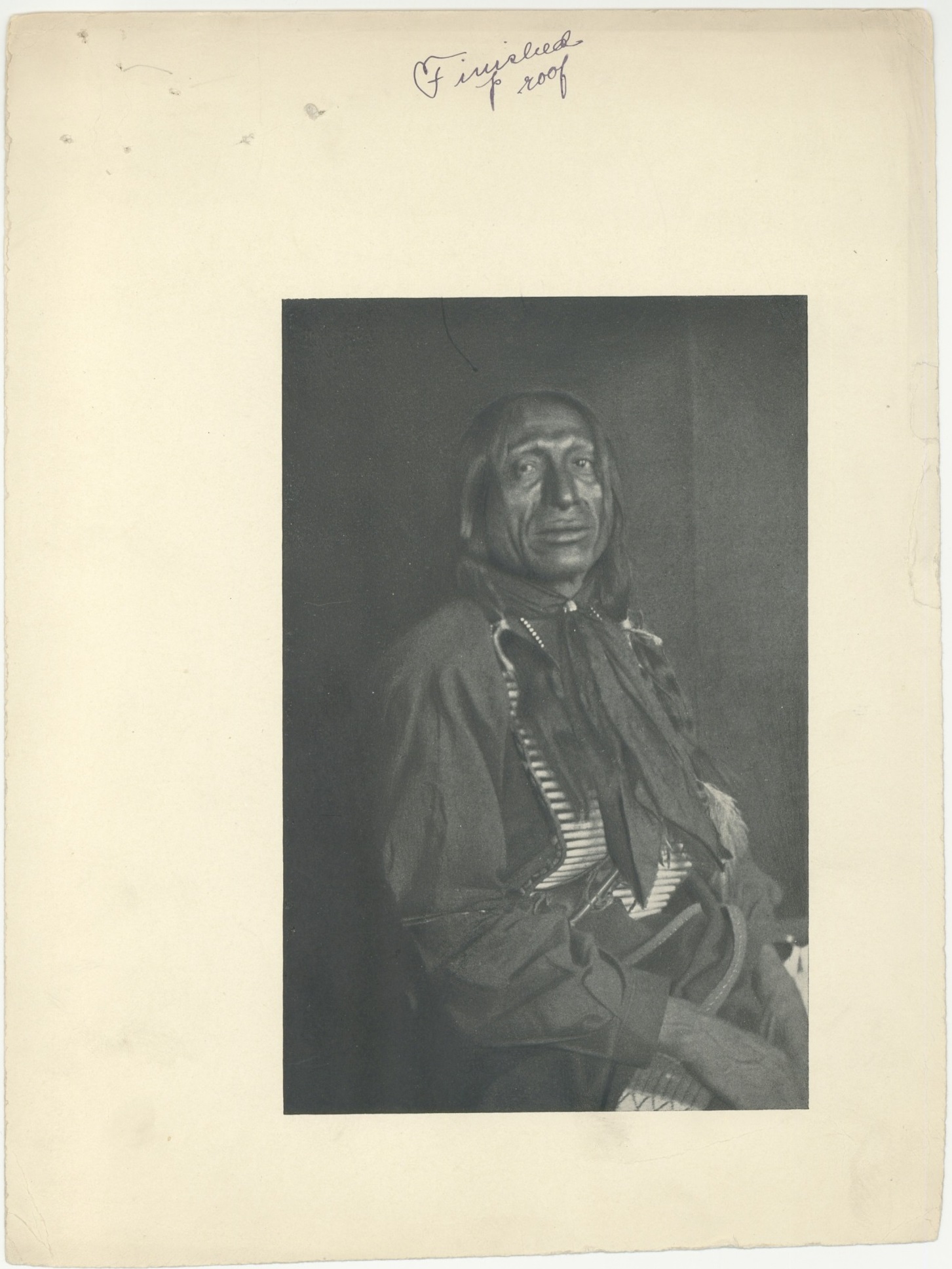

At least twice in the spring of 1898, Siŋté Máza visited the New York studio of photographer Gertrude Käsebier (1852–1934), who invited him as part of a group of the Lakȟóta performers she had seen in a Wild West parade whom she asked to pose for “a private photograph gallery.”33 She made two photographs of Siŋté Máza. In one, the sitter’s only markers of Lakȟóta identity are his long hair and his hairpipe shell vest, which is largely covered by his hair and dark handkerchief (fig. 2). His unfocused eyes look slightly to the side with a pensive expression, his hands resting in his lap. His face and hands are slightly blurred, falling out of the camera’s selective focus, which is crisp across his chest and torso. When Käsebier published portraits of Lakȟóta performers—along with photographs of other American Indian sitters, including Yankton Dakȟóta writer and activist Zitkála-Šá (Gertrude Simmons Bonnin, 1876–1938)—in an anonymous 1901 article in Everybody’s Magazine of which she was likely the author, she used this photograph of Siŋté Máza for the frontispiece with the caption: “This portrait was made with his feathers and other decorations removed, the photographer declaring that she wished to take a real ‘raw’ Indian.”34 Though Käsebier did not publish it in photographic journals of the period, the article declared it “the most remarkable portrait of the whole collection.”35 In the second photograph, Siŋté Máza poses in profile facing right and wearing a war bonnet (fig. 3). When printed in Everybody’s Magazine, its caption read: “A portrait made in full regalia, because of his dissatisfaction with the undecorated one.”36 The two captions suggest that Siŋté Máza and Käsebier understood the sitting from different perspectives. In the first caption, Käsebier explains the photograph as a realization of her intentions. In the second, she acknowledges Siŋté Máza’s deliberate effort to use the sitting for his own purposes. These distinctions suggest a tension in goals between photographer and sitter. This section parses their separate investments and explores the ways in which Siŋté Máza, and the other Lakȟóta performers, acted as collaborators in image making.

In line with photo historians’ tendency to focus on maker more than subject, much of the scholarship on these photographs has focused on Käsebier’s positionality. Her romantic ideal of a pure or authentic Indian—in part based on her childhood travels to the West—shaped her construction of these images, which drew on tropes of ethnographic photography.37 Lauren Kroiz has suggested that Käsebier’s photographs of Native Americans connected her aesthetic practice with frontier mythology to present her photographs as unencumbered by civilization.38 Due to Käsebier’s attempts at self-expression through her sitter’s experience, thus “slipping into [the Indians’] skin in her mind’s eye,” Judith Davidov has critiqued the photographer’s “invasive” act of “‘trying on’ otherness.”39 Likewise, Laura Wexler frames Käsebier’s American Indian photographs through the interwoven lenses of gender and the rhetoric of colonialism. She argues that the artist’s series complements imperialist power while cloaked in a discerning innocence linked to her gender.40 Elizabeth Hutchinson also links Käsebier’s American Indian photographs to gender, analyzing how the photographs and the surrounding publications reveal the gendering of the artist’s studio.41 These analyses are important for their focus on questions of the photographer’s agency, gender, and politics, but they explore only half the story.

The photographs have not yet been considered fully from the sitter’s perspective. Furthermore, existing scholarship frequently silences the possibilities of Siŋté Máza’s agency. Jennifer Sheffield Currie suggests the photographs leave viewers with “little sense of Iron Tail as an individual.”42 In discussing the first photograph (fig. 2), Davidov declares Siŋté Máza “a man defeated, exposed, and vulnerable.”43 Wexler describes him as a symbol of “the late nineteenth-century Native American in his raw predicament.”44 These conclusions draw not only from formal readings but also from descriptions of the sittings, from the 1901 article in Everybody’s Magazine and another, also probably written by Käsebier, printed in the New York Times in 1898. These articles narrate the production of the first portrait (fig. 2) from the photographer’s perspective, in which she chose Siŋté Máza “quite at random and proceeded to divest him of his finery” to attain a portrait of a “real raw Indian.” The articles emphasize her control over her sitter, who “said never a word, but obeyed instructions like an automaton.”45 This demeaning tone frames Käsebier’s adoption of power, but we might also read beyond perceptions of Siŋté Máza’s victimization to uncover his agency.

Subtle inconsistencies in the record suggest the romanticized conceit being built around the photographs. The New York Times declared Käsebier’s surprise at her street-level encounter with Buffalo Bill’s Wild West parade, whereas the Everybody’s Magazine article instead describes the artist’s bird’s-eye view over the street while ensconced in her studio. Two different stories circulated about the reason for having two photographs of the sitter. Despite the fact that, in line with current anthropological practice, many Lakȟótas, like Siŋté Máza, posed for both frontal and profile photographs raising the possibility that Käsebier made the decision to make two photographs, the stories about the sittings both attribute the request to Siŋté Máza.46

The articles explain that Siŋté Máza disliked the first photograph (fig. 2), dramatically narrating that when he saw the print, he “tore it in two and flung it from him,” although they cite different reasons for his purported rejection of the image.47 The initial account argued that the sitter found the photograph “too black.” Based on the newspaper’s follow-up, the complaint likely refers to race: “Now he is having a picture taken to look white.”48 As Tanya Sheehan has considered, the medium of photography itself “served as a ready metaphor for racial difference” and “operate[d] as an instrument and metaphor for race relations” with its capturing of light and its negative-positive process that inverts tonal values.49 Within this discourse of photography and race, Sheehan analyzes conversations among US photographers about how to use lighting to whiten sitters’ faces. She discusses a satire in which a sitter of “dark brown complexion and black hair” complains the portrait was “altogether too dark” and, pointing to another cabinet card depicting himself, “I want mine . . . white as that.”50 This period language related to the racialized framing of photographic flesh as “too dark” suggests that Siŋté Máza’s objection to Käsebier’s photograph may have been that his image appeared to his eye as the face of a black man. The letterpress half-tone print of the image labeled “finished proof,” probably the one used for the periodicals (fig. 4), renders his skin even darker than the most frequently reproduced platinum print. Siŋté Máza purportedly demanded another sitting, although the New York Times assuaged readers about the anxious implications of the camera’s ability to lighten the sitter’s complexion and potentially permit the Lakȟóta man to pass as white: “Natural conditions will prevent his appearing too much like a paleface.”51 In the second photograph, however, the highlight on his cheeks markedly lightens his face (fig. 3).52

The subsequent essay in Everybody’s Magazine replaces the sitter’s critique of appearing “too black” in the initial photograph, attributing Siŋté Máza’s disapproval of the image instead to his being disarmed and without regalia. The article narrates that it was:

perhaps not fanciful to read something of the misery which he was really undergoing. For the truth was that every feather represented some act of bravery either on his own part or that of his ancestors. This superb old Sioux (who probably took part in the Custer fight nearly a quarter of a century ago) had been a mighty man of battle; the number of his plumes stood for enemies slain . . . without sentimental exaggeration, it was a tragedy to the veteran.53

Käsebier’s imagination projects a battle history for her sitter that skews his biography and mythologizes him as a surviving remnant of this past. Her granddaughter also recollected that the Lakȟóta performers had been uncomfortable with sitting for the photographer due to longstanding perceptions that Indian sitters were superstitious that the photographic image could nab their souls.54 Given the array of surviving photographs of Siŋté Máza in and out of Lakȟóta markers, claims of his discomfort for either reason seem ill-fitting and align with stereotypes that Vizenor has critiqued as “manifest manners.” They do, however, underscore Käsebier’s story about assuaging her sitter’s frustrations with the second sitting, which aligns with the archetypal imagery of the Indian circulating at the time in the United States, as the iconic feathered war bonnet takes up most of the pictorial space in which the sitter poses in honorific profile (fig. 3).

While we do not know what dialogues Käsebier and Siŋté Máza may have had about the images, or if he destroyed the first print, we can analyze the sitter’s navigation of these photographic opportunities by defining artistry broadly and by placing these photographs within the larger context of Käsebier’s series depicting Lakȟóta performers. Siŋté Máza’s identities within and outside performance spaces are not necessarily equivalent. His sitting for Käsebier was part of his career as a professional performer, and his other frequent photograph sittings suggest how important photography was in his efforts to build celebrity and mythology around himself. The performers, referred to as Oskate Wičháša in Lakȟóta, can be understood as artists whom Käsebier renders in the act of performing.55 In her photographs, the cloth backdrops mark her artist’s studio space as distinct from the painted backdrops in the commercial photographer’s space.56 This location and overlapped context of art making reinforces Siŋté Máza’s collaborative artistic relationship with Käsebier.

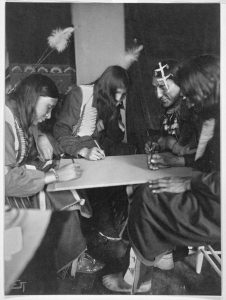

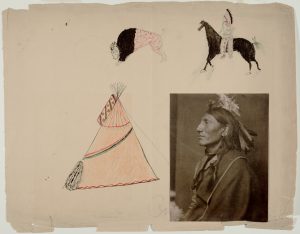

Käsebier highlights this collective inter-media artistry in some of the photographs that render the Lakȟóta performers making drawings in her studio. In one example, four performers, including Sam Matȟó Išnála (Sam Lone Bear, c.1878–c.1945) and Joe Šuŋǧíla SápA (Joe Black Fox), sit around a table, each with a sketching implement in hand and leaning over a single large sheet of paper (fig. 5).57 One such shared art-making session resulted in a studio collaboration now in the collection of the National Museum of American History: one of Käsebier’s platinum prints of Tȟašûŋke Nahómni (Whirling Horse) is pasted on a sheet of paper with three drawings perhaps made by the sitter (fig. 6).58 The portrait is placed at lower right as though the left-facing figure contemplates his own drawings of icons of Plains life—a tipi, a bison, and a drawn figure wearing regalia while sitting on horseback. Such imagery and the schematic aesthetic are often seen in Plains hide paintings and ledger drawings of the period, as Lakȟóta men continued the longstanding practice of narrating historical events and Lakȟóta stories in the midst of assaults on their culture.59 The pairing of drawn and photographed representations implies an intercultural (albeit asymmetrical) shared production between artists. It echoes the relational contacts between earlier portrait artist Karl Bodmer (1809–1893) and the Numak’aki (Mandan) sitters who made drawings before sitting for painted portraits in what Kristine K. Ronan has described as a “co-creation process.”60

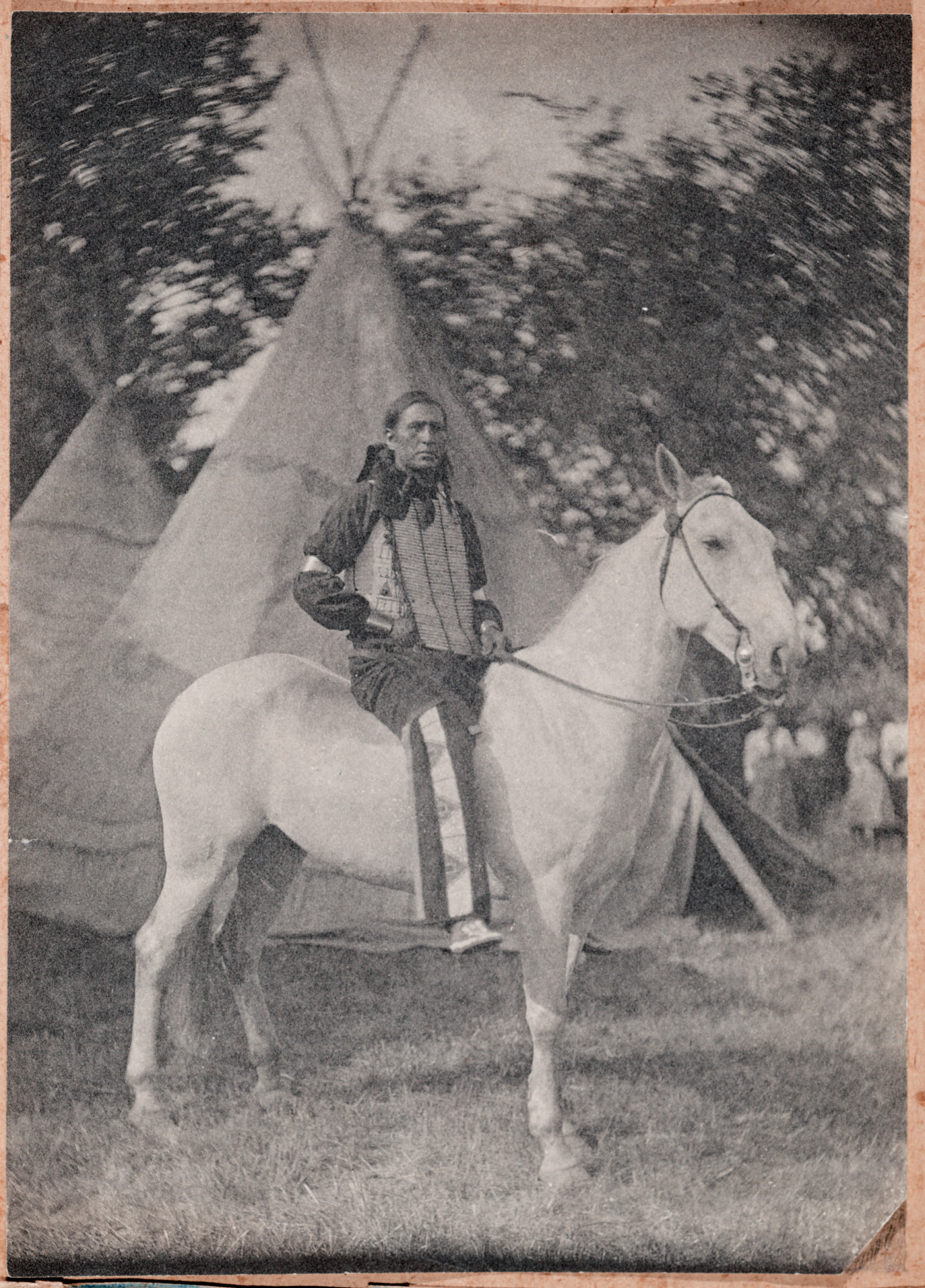

Many of the Lakȟótas’ sketches from Käsebier’s studio are extant. They parallel drawings made in Buffalo Bill’s Wild West encampment in the 1890s that were reproduced in contemporary articles.61 As both a performance space and a space for art making, the Buffalo Bill’s Wild West environment acted as an expansive studio. Käsebier made at least five photographs of the performers at Buffalo Bill’s Wild West encampment, in addition to those made in her Fifth Avenue studio, and her visits to this “studio” of the Lakȟóta performers extended their aesthetic collaboration.62 Her photograph of Hokȟá Wankátuya (High Heron), with the sitter on horseback gazing off into the distance, underscores the performance context, with four blurry non-Native observers in the background (fig. 7). The photograph further frames Lakȟóta artistry through the decorated tipis, which were often painted by the performers, and the regalia in the beaded strip on Hokȟá Wankátuya’s pants and his hairpipe shell vest.

Scholars have dismissed the objects worn and used by Wild West performers in Käsebier’s photographs as costumes and props. Wexler writes, for instance, “It seems safe to surmise that the purpose of Iron Tail’s costume must have been as much related to masquerade and disguise as to any show of military might.”63 She continues, “The tribal dress, re-assembled as a bricolage of trinkets, was not a sacred statement. It was expressly adopted that morning in order to give a white woman ‘an Indian’ to photograph.”64 To be sure, the fungibility of the bonnet as an alleged identity marker is revealed through its appearance in several photographs of some of the older sitters; the same bonnet appears in Tȟašûŋke Wamníyomni (Whirlwind Horse’s) and Śuŋkaḱaŋ Nica (Has No Horses’s) photographs. In its repurposing, the bonnet’s link to a warrior tradition loses the individuality claimed by the articles; the feathers might inflect someone’s coups, but not necessarily those of the person wearing them.

But we need not dismiss so quickly the cultural importance of these objects. While their meanings shift in the performance context, they do not become empty signifiers. The beaded band connecting the feathers on the bonnet marks the triangular tipi pattern typically found in the careful line stitching of Lakȟóta beadwork (see fig. 3).65 Thorough study of Käsebier’s photographs of Lakȟóta sitters wearing war bonnets reveals at least seven different beaded patterns along the bands, and some examples do not repeat across sitters. The hairpipe shell vests, bonnets, and beaded objects worn by the performers were made by women in the Lakȟóta community, who perpetuated and even expanded these longstanding cultural practices in the face of fiercely-mandated assimilation. Not mere souvenirs or costumes, the objects that traveled with the show in this period are indistinguishable from objects that remained within the community.66 The movements of Lakȟóta performers and objects circulated Lakȟóta culture and acted as a statement of continued presence and adaptation in parallel with the cultural assertions made through drawing.67

The meanings that Käsebier built through these sittings need not disqualify the meanings that emerged for her sitters. What she framed in Everybody’s Magazine as Siŋté Máza’s erased veteran status and, by extension, another symbol of Lakȟóta defeat was actually the inverse; in both photographs, Siŋté Máza’s signaled himself as a symbol of Lakȟóta survivance, adaptation, and artistry. His biography, the relationship between these photographs, and the wider array of images of Lakȟótas that Käsebier produced during this period underscore his relationality and navigation of non-Native spaces. Instead of assuming that the two photographs render failed and successful projects, respectively, we might frame Siŋté Máza’s mobility as enabled across their differences. This relationality enacts his deflection of singular archetypy.

Rome, 1906

Buffalo Bill’s Wild West performers often capitalized on the opportunities enabled by international travel. They earned more money than they could have within the reservation system in the Dakotas and escaped the watchful eye of government agents. Some embraced foreign presses as mouthpieces for critiques of US settler colonial incursion.68 Tourism provided another benefit to traveling performers; on a tour in England in 1902, Luther Matȟó Nážiŋ (Luther Standing Bear, 1868–1939) recalled his opportunity to “see many wonderful sights and visit many interesting places” in London, and during the tour he noted that he and others would purchase “things to carry back home, such as nice blankets and shawls.”69 Another performer, Jacob Ištá Ská (Jacob White Eyes, c. 1870–1935), sent tourist postcards (including one of a Wild West parade in Paris in which he is pictured) to a French correspondent during the 1905–6 tour around Western and Eastern Europe.70 Like his fellow performers, Siŋté Máza benefited in various ways from the mobility enabled by working with Buffalo Bill’s Wild West, even as it reinforced stereotypes of Indianness for non-Native viewers.

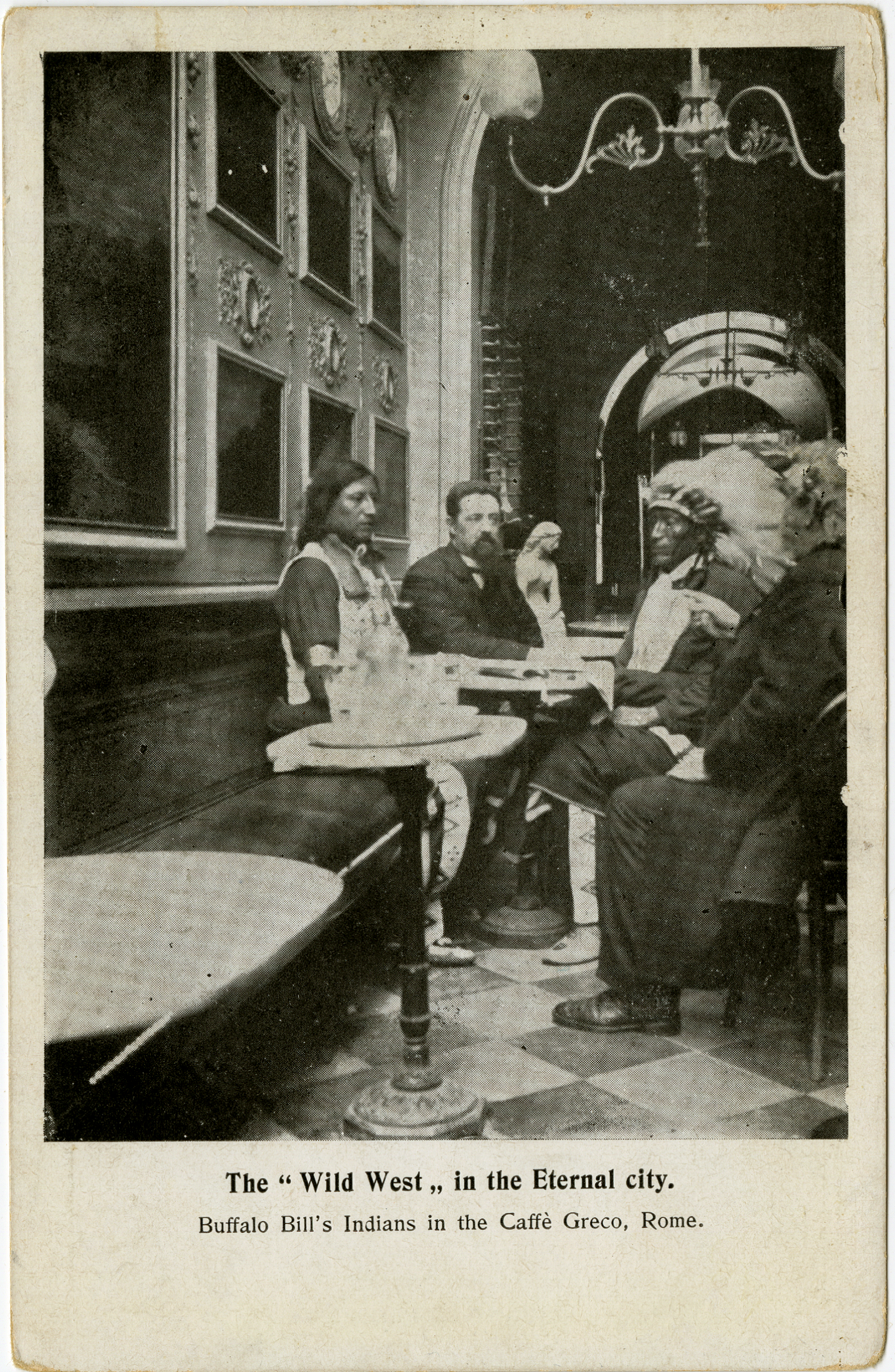

In Rome in 1906, Siŋté Máza drew attention to these relational movements. With Jacob Ištá Ská, John Burke (1842–1917), and another white man, he visited the Caffè Greco.71 The men joined a long line of artists who had congregated at the location, which is the oldest bar in Rome.72 Ludwig Passini (1832–1903), an Austrian painter based in Rome in the mid-nineteenth century, rendered the interior in Caffè Greco in Rome fifty years before the Lakȟóta performers visited (fig. 8). Differences among the figures in the group of men seated at right in Passini’s painting are implied by their various hats and clothes, yet the artist presents a space of fluid encounter, integration, and exchange in the café context. With exhibition announcements hanging visibly on the wall, Passini also connects the space to the art world.

At the café in late March 1906, in the long, narrow gallery visible in the back right of Passini’s painting, Siŋté Máza embraced another photographic opportunity.73 It was probably the same unknown photographer who took three similar photographs of the four men sitting at a set of oblong tables along a banquette. In two, the sitters appear engaged in casual conversation, reminiscent of the international male camaraderie in the Caffè Greco figured by Passini (figs. 9, 10), perhaps discussing the reviews of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West in the newspapers resting on the table. A tray of empty glasses on the table next to the figures implies that they have already enjoyed drinks in the café. The poses are so close and the perspective so similar that we might imagine the photographs being taken just moments apart. In a third photograph, which appears to have been taken earlier, both Siŋté Máza and Jacob Ištá Ská look directly at the camera (fig. 11).74

As with Käsebier’s photographs, these representations exhibit a tension between the intentions of the photographer, who was probably trying to produce an advertisement for the café by rendering its “exotic” patrons, and of the sitters, who not only might have benefited from a paid publicity sitting but who also underscored their role as artist-performers within the larger transnational character of the café and as tourists in the ancient city. The complex photographs can accommodate both possible contradictory readings; the photographs reinforce ideas of possession, exoticism, and power, but they also subtly defer and deflect these conceits.

The first of these three images was turned into a postcard published by Cartolina Postale Italiana and inscribed on the verso with the name of the café, its manager, Federico Guibinelli, its founding date of 1760 and its location at 85 Via Condotti (see fig. 9). Adopting a European form of “manifest manners,” Vizenor’s term for primitivizing stereotypes about Indians that justify settler colonialism, the photographer attempted to create interest in the café by juxtaposing New World and Old, as feathers and beads contrast with marble tabletops and tiled floors. This constructed incongruity is highlighted by the caption: “The ‘Wild West’ in the Eternal City: Buffalo Bill’s Indians in the Caffè Greco, Rome.” The foreground tables remain tantalizingly empty, as though future patrons could enjoy the café near such an exotic group. The framing affords a wide view of the café, and the image creates opposition between, on the one hand, the stucco walls with foliate patterns around embedded pictures, decorative tile floor, and chandelier, and on the other, Siŋté Máza silhouetted against the wide arch in the background. This composition builds distance and a tension between the Lakȟóta figures and the history and tradition of European civilization, which may explain the selection of this photograph, from among at least the two other images, for the advertising postcard.

But while the photographer tried to convey a sense of the incompatibility between the Lakȟóta performers and the European café setting, closer inspection reveals aspects of the images that undercut that attempted thesis. The figures’ insistent integration into the space subtly negates the intended juxtaposition. Siŋté Máza and Jacob Ištá Ská direct attention to their mobility, where they sit comfortably as tourists alongside non-Native men. As Pinney has argued, the spread of photography in the nineteenth century was tied with travel because the medium’s indexicality implied “being there.”75 In an inversion, Siŋté Máza and Jacob Ištá Ská follow this convention with their presence, using the sitting in this setting as an opportunity to display themselves as encoded travelers concurrent with their environment. They build a fluid space, unabashedly of past and present, modern and Lakȟóta.

The diversity of clothing among this group is not so far afield from that exhibited by the diverse men in Passini’s painting. Both Lakȟóta men wear Lakȟóta regalia; Ištá Ská wears a single feather, a hairpipe shell vest, pants with beaded trim, and beaded moccasins, while Siŋté Máza wears the same type of clothing and a many-feathered war bonnet similar to the one he wore in his sitting with Käsebier (fig. 3). In their pairing with the white men and compatibility with their environment, their regalia underscores them not as remnants of a so-called “vanishing race” but instead as representatives of a surviving and circulating community that moved fluidly through European cities. Burke’s presence, as the publicity manager for the show, upends the scene’s implied exoticism as well.76 As we imagine the conversations around the papers on the table, the figures view the performative spaces of Wild West display from a public space outside the encampment and arena. These details render visible gaps between Indian selves on- and offstage that many contemporaries elided.

One of the photographs, perhaps pointedly not chosen for the advertisement, offers a meditation on the very concept of representation and archetype (fig. 11). Instead of witnessing a ludic encounter from several tables away, the photographer seems situated closer to the sitters at a nearby table. Centered within the group on the table are a statuette and bust, both US-born icons rendered in plaster: the statue depicts Mark Twain (1835–1910) standing full-length with one hand casually in his pocket and the other holding a cigar. The bust figures Burke himself, his moustache and cowboy hat echoed in the silhouetted bust beside him. A rectangular page with a faded image of a third bust stands between the plasters. Both Ištá Ská and Siŋté Máza also hold rigid papers that bear faint outlines of images, perhaps portrait photographs or the backs of the café menus. This pairing of Lakȟóta performers with the sculptures and photographs on the table unsettles the typical photographic frame. Rather than exoticized representations, Ištá Ská and Siŋté Máza are bodily present in person, more ”real” than the representations they hold and consult, more especially than the sculptures—other icons of US culture—which are presented almost as props. The image unwittingly plays with the construct of what is “native” to the United States by pairing the Native American figures with quintessential white Americans abroad. Twain and Burke both had histories of traveling in Italy; Twain in 1867 as part of the grand tour he satirized in The Innocents Abroad, and Burke with an earlier group of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West performers in 1890. Ultimately, the image presents a pluralistic array of Americans abroad. Attempts to imply a clash of Old and New World civilizations, and between European and American, are upended by these nuances. That the photograph was not chosen for wide circulation in the form of a postcard reproduction might suggest unease with the ways in which the image undercuts the narratives attempted, but deflected, by the selected image. In the presence and pose of the figures, paired with the sculptures, the sitters unsettle the construct of old and new as they refuse to act as mere empty icons of Indianness.

Cody, around 1908

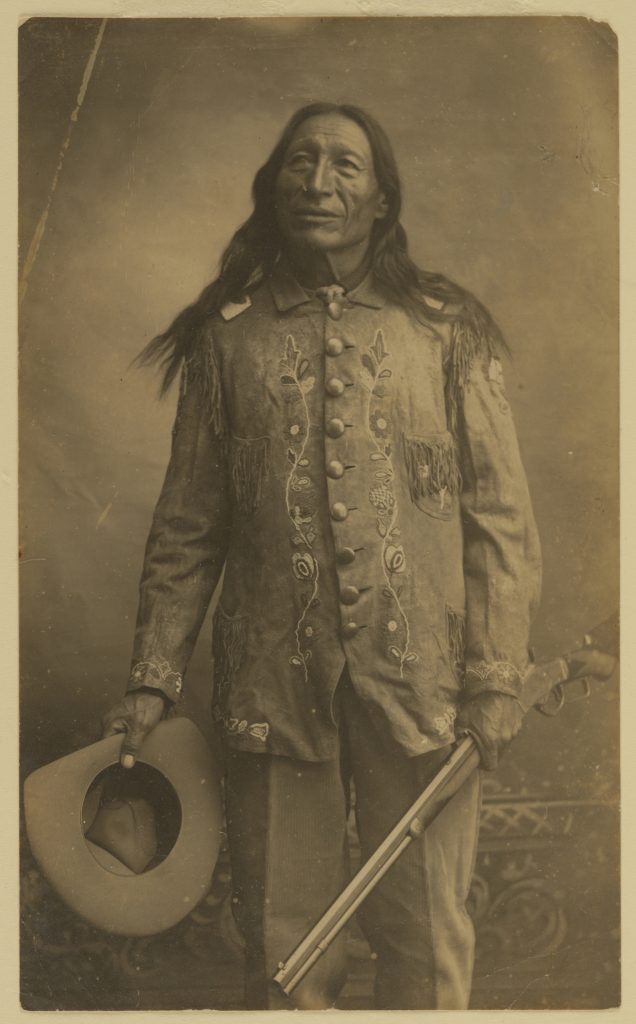

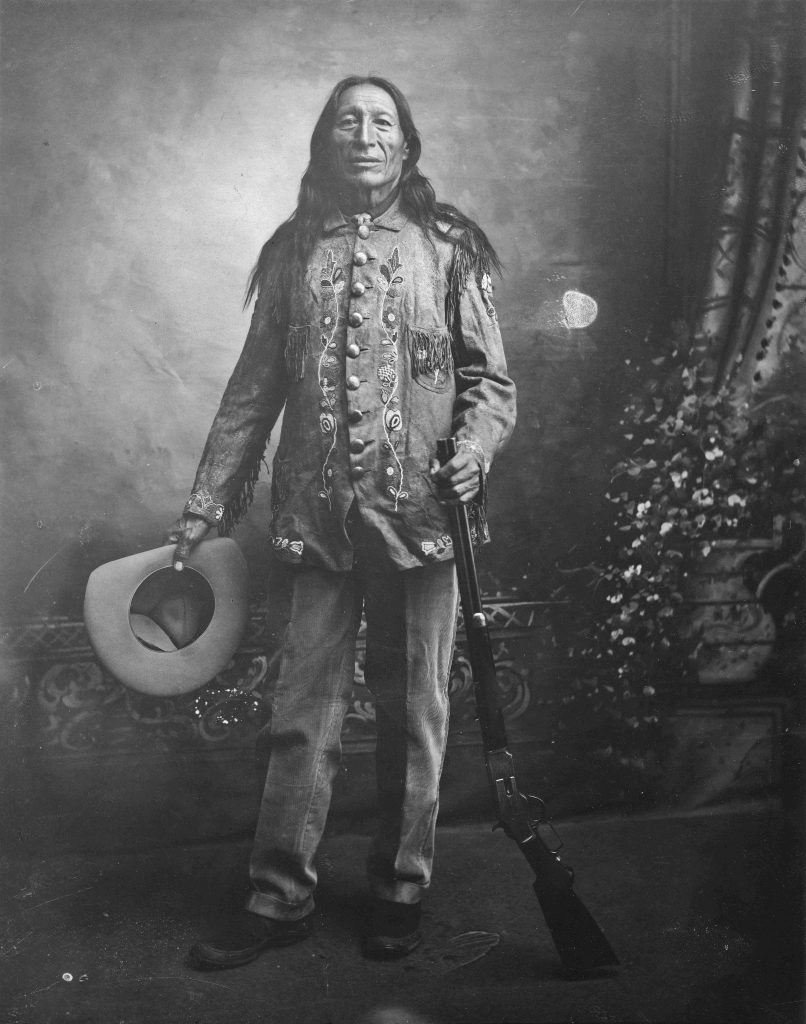

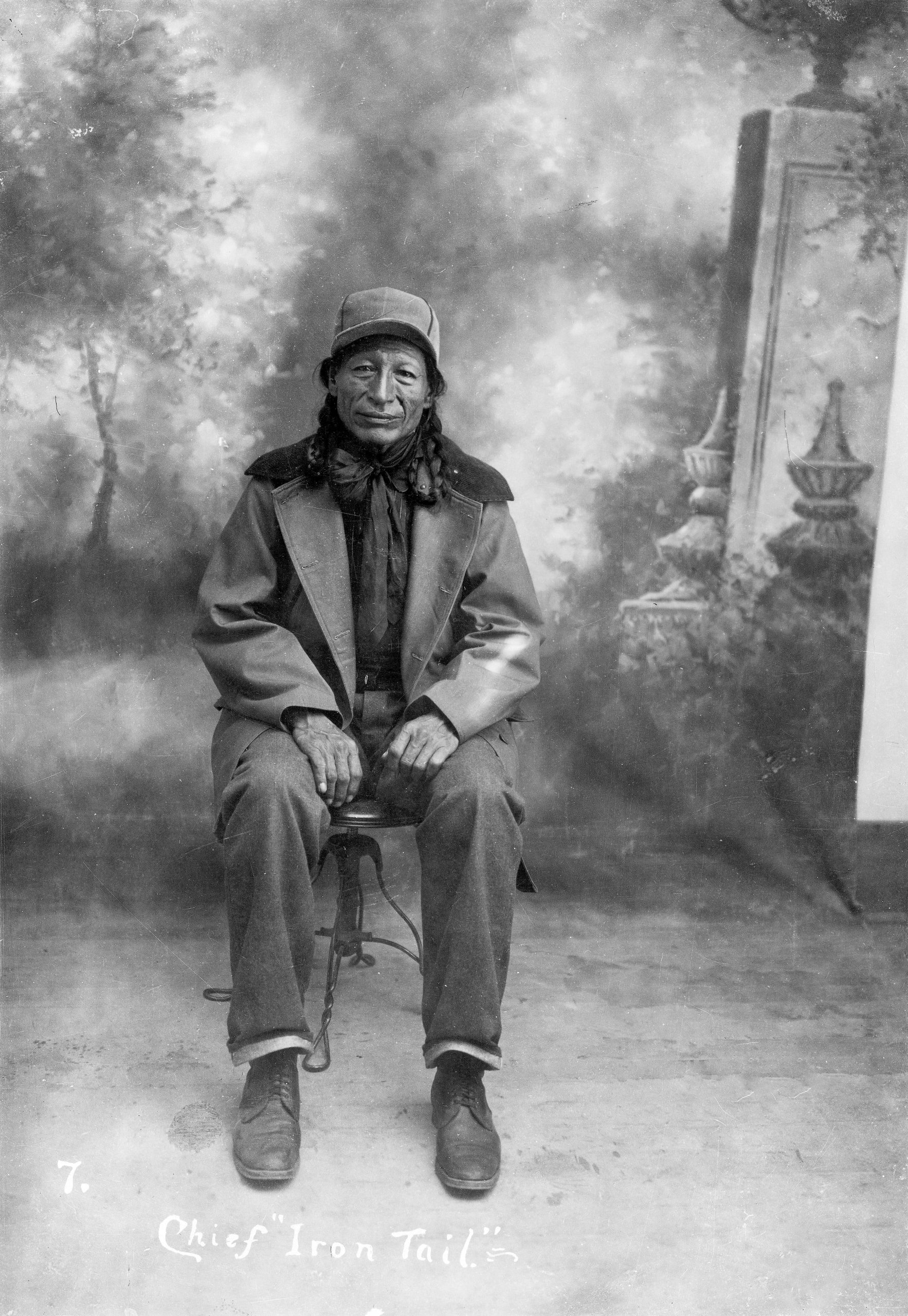

Ten years and hundreds of photographs after Siŋté Máza sat for Käsebier in New York, he seems to have sought to have commercial studio portraits made. Outside of the Lakȟóta regalia he typically wore, in these photographs, he wears western hunting clothing and an embroidered jacket probably made in the Cree nation (figs. 12, 14, 15). These photographic opportunities and the sitter’s juxtapositions between backdrop and clothing enact his relational transits in identity positions. In his use of the commercial studio to produce a certain image of himself, Siŋté Máza embraces aspects of the medium that, according to anthropologist Arjun Appadurai, upend expectation: “Photography invites its own subversion, exemplified in the playfulness, pastiche, irony, and stylized distortions of backdrops and other props.” Appadurai registers both the “visible backdrop and the invisible backdrop,” the literal image and the cultural constraints that shaped the photographic moment.77 Siŋté Máza brings both levels to the surface with these complex images that unsettle archetypes of Indianness. While photography in ethnographic contexts sought to convey an oppressive depth of cultural knowledge, through his clothing and backdrops, Siŋté Máza thwarts expectations of anthropological information.78 Pinney has argued that in the adaptation of studio photography within asymmetrical power relations, “surface becomes a site of the refusal of the depth that characterized colonial representational regimes.”79 In studio portrait photography in India and West Africa, he argues, the human body becomes “a surface that is completely mutable and mobile, capable of being situated in any time and space.”80 Siŋté Máza’s studio portraits mark an example of the subversion and play that Appadurai and Pinney perceive. The photographs offer incongruities in location and clothing that upend stereotypes and the expectations of “manifest manners.”

Siŋté Máza visited Cody, the eponymous town that William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody had founded in 1896, at least four times in the first decade of the twentieth century to participate in Cody’s hunting trips nearby.81 Wyoming became a state in 1890, though population growth was slow. The frontier town fifty miles east of Yellowstone National Park slowly accommodated European features, notably the large foliate cherrywood bar installed in the Irma Hotel in 1902. In this borderlands space, portrait photography offered locals an environment to demonstrate westernness against the refinements of painted backdrops that evoked elite interiors and European-style gardens. F. J. Hiscock (1873–1951) opened a photography studio in Cody in 1904, advertising for portrait sittings with a tone of western boosterism, first in the back of a tack shop and later in his own building.82 In 1910, Cody wrote to Hiscock with an envelope addressed simply to “the picture man,” announcing him as a “grand advertiser for our town and country” and stating, “I want to encourage you all I can.”83 Cody’s “encouragement” likely included recommending the photographer to or funding portraits of Siŋté Máza, who had at least two sittings in Hiscock’s studio.84

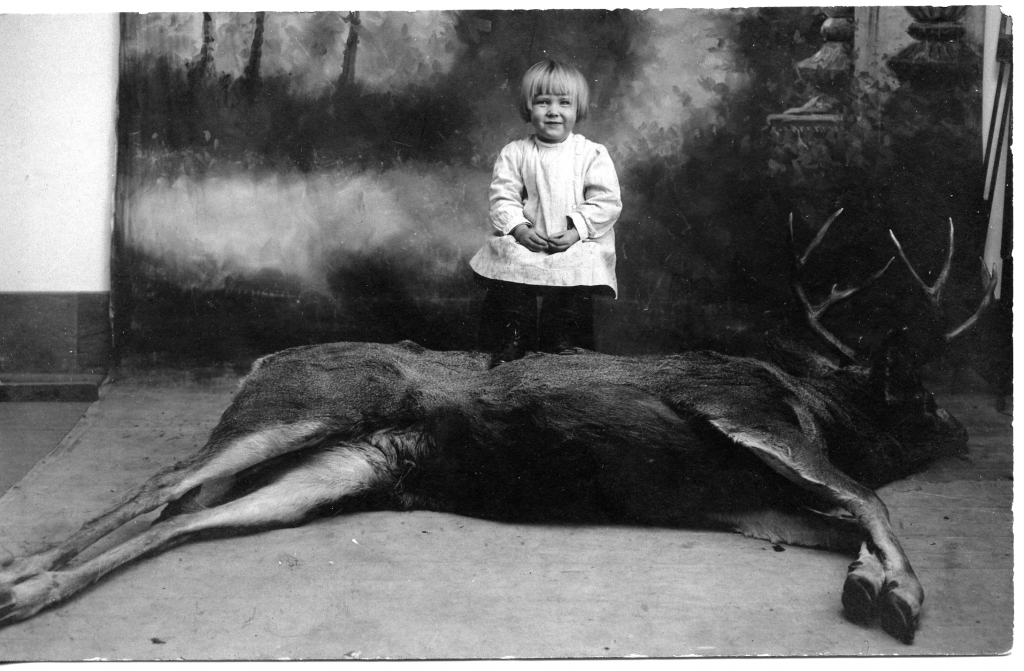

In these privately commissioned photographs, Siŋté Máza deflects the wider commercial market that capitalized on exoticized images of Indians. One of Hiscock’s photographs depicts Siŋté Máza in western clothing—the same trousers, hunting cap, leather coat and shoes he wears in other photographs taken during hunting trips (fig. 12). This clothing choice for his portrait sitting suggests that Siŋté Máza sought a distinct identity from that expected of a Lakȟóta celebrity. Through clothing, he upsets the archetype. He sits on a stool against a feathery backdrop with trees, his hands calmly poised in his lap and looking directly at the photographer. This sitter uses the same painted backdrop that appears in other contemporaneous portraits by Hiscock, including one of the photographer’s daughter posed with her feet resting on the body of a massive dead mule deer (fig. 13).85 To the right, in the painted backdrop, a weathered and slightly overgrown stone plinth is flanked and topped by decorative vessels. The scene appears as an elite country garden, far away from the small western town of Cody. For both sitters, the backdrop becomes part of the imaginary constructed space in which they sit. Yet in both photographs, there is a tension between the imaginary, genteel, feathery garden of the backdrop and the frontier town in which the portraits were made. Hiscock’s daughter is anchored in Cody by the hunted carcass beneath her feet. In the photograph of Siŋté Máza, the studio construct is rendered visible due to a triangle of white that disrupts the photograph’s right edge. His western hunting clothing also clashes with the genteel localization of the backdrop. These contrasts draw attention to various registers of place simultaneously. While the studio space transports him away from Cody, his clothing grounds him in place within the western hunting community.

Siŋté Máza builds on his complex and transitory identity in another pair of photographs taken in Hiscock’s studio, in which he stands against a painted backdrop embellished with a lightly painted foliate pattern, an urn of flowers, and an imagined curtain while wearing a garment probably produced by a woman artist from the Cree nation (figs. 14, 15).86 As with the previous backdrop, this background positions the sitter’s performative transit far from the western space of Cody, but his clothing re-situates him in Wyoming’s hunting grounds. His hair is long and loose, and he leans on the Winchester 1873 rifle he holds in one hand. His other hand grasps a cowboy hat. In both images, he stands confidently, in one looking directly at the camera and in the other upward to the sky. Returning to the rhetoric of darkness in Käsebier’s first photograph, highlights on the sitter’s face in both compositions lighten his skin tone. The full-length print (fig. 15) is large and mounted on a gray board embossed with the insignia of the Hiscock studio, as though intended to be placed in a parlor.

In both photographs, the foliate patterns of the painted backdrop are echoed by the designs along the front of Siŋté Máza’s jacket. He wears an embroidered jacket which is extant (fig. 16), and pressed pants that bear vertical creases on the legs. The jacket’s design is not typically found in beadwork made by Lakȟóta women, which is characterized by linear strands of beads and more abstract motifs; instead, its design is characteristic of Cree beadwork, with a sinuous floral pattern framing the buttons and schematic flowers made from concentric circles of beads.87 The buttons on the front of the jacket, however, reveal it as a hybrid shirt; unlike typical Plains shirts, which are usually pulled over the head, this is modeled after settler clothing, which opens in front and has sleeves. These images draw on longstanding trade among Native communities to extend Siŋté Máza’s photographic circulation of Native regalia from the Lakȟóta nation to a community other than his own.

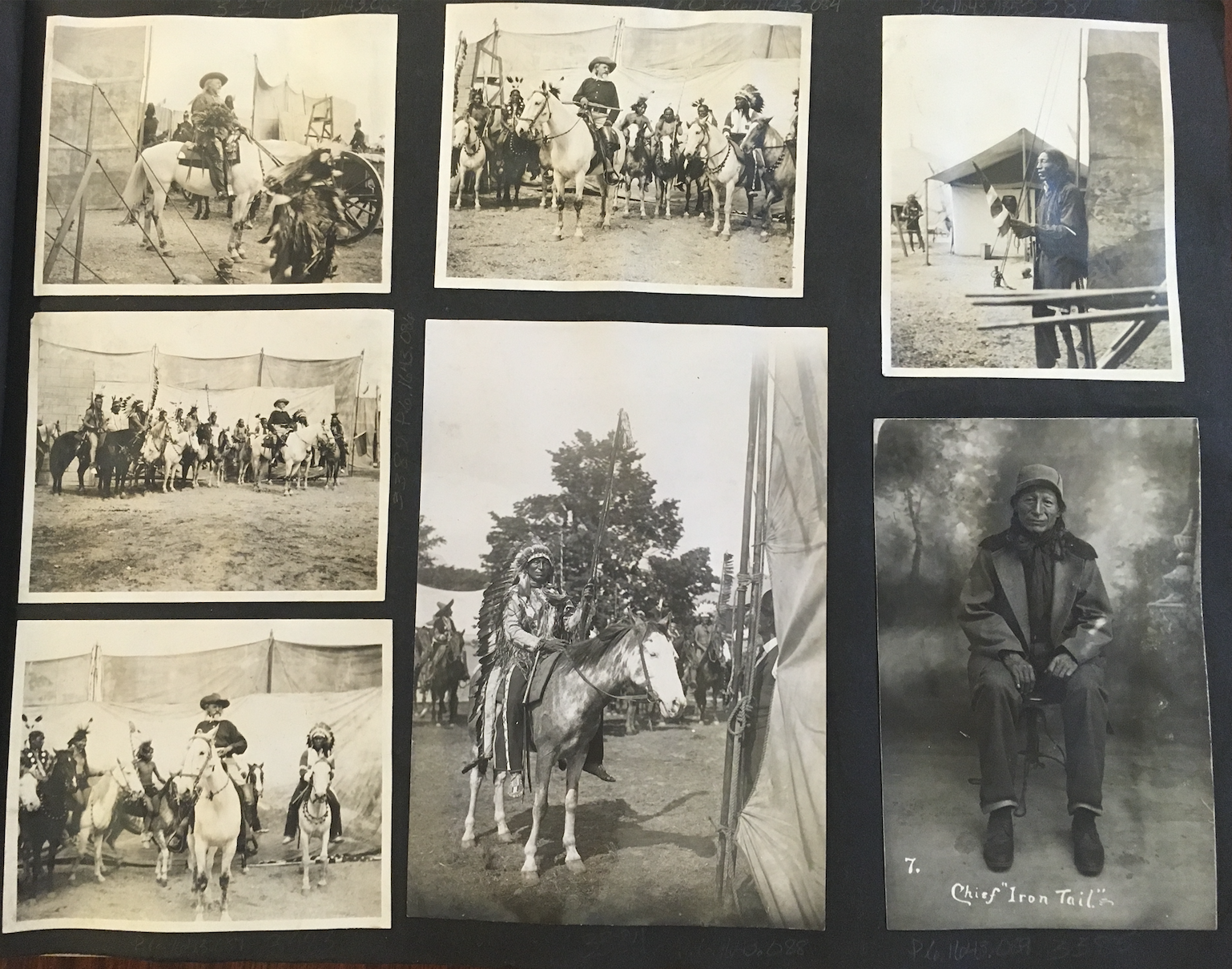

The photographs also frame his relationship with Cody, because Cody lent this jacket to the Lakȟóta performer, along with the rifle and hat, for the sitting. Cody himself wears and wields these items in another Hiscock photograph (fig. 17). This shared garment ties Cody and Siŋté Máza—who were labeled the “two unique figures in the show”—more closely together.88 The two fellow showmen shared performance strategies; reviewers commented on both men’s charisma and ability to charm audiences. The sharing of Native-made garments appears to have been common within the Wild West performance community. A bright yellow, ochre-dyed Plains jacket with figurative beading of US flags and horses also survives (figs. 18a, b).89 The name “Iron Tail”—along with the names of the subsequent performers who owned the jacket, many of whom were vaqueros, Mexican cowboys who performed in Buffalo Bill’s Wild West—is inscribed in pencil on the leather’s inside. At some point in the passing of the object, the jacket was enlarged through the addition of a strip of leather along the center of the back, and an additional beaded horse added over that center piece. This bestowing of fine hand-made regalia draws on the longstanding tradition of the Lakȟóta giveaway, in which individuals show their generosity and wealth by offering goods to other members of their community.90 In Siŋté Máza’s case, the sharing of Native jackets and the labeled genealogy inside the jacket reveals his communities, which were comprised of overlapping Lakȟóta, other Native, and settler contexts. We might assume that these objects became empty signifiers appropriated as costumes in Wild West performance. Yet we might also read the circulation of these beaded objects as public testaments of survivance that retain longheld “epistemological ties to the land and culture of their makers.”91 Cody and Siŋté Máza encouraged this circulation of Native American art more broadly, by Lakȟóta and also by Cree makers, in tours and in photographs, such as the ones for which Siŋté Máza posed in Hiscock’s studio.92

Hiscock’s photographs were not necessarily exclusively private commissions. The photographer also sold collections of photographs of the Yellowstone region in his studio or by mail order, one of which included the photograph of Cody wearing the Cree jacket (fig. 17).93 Negatives of these images are typically etched with a number to correspond with Hiscock’s accompanying inventory lists. I have not yet found a tourist series that includes the photograph of Siŋté Máza wearing western clothes, but the etched number seven and name beneath the figure’s feet suggest that it probably was included in such a set (fig. 12). If the photograph did circulate in these collected photograph packs, its distribution cultivated a more nuanced image of this Lakȟóta performer than was typical. Another print of this photograph of Siŋté Máza in western clothes appears in an album of Cody’s tours, pasted alongside other representations of Siŋté Máza in regalia where it, too, complicates his story (fig. 19). Hiscock’s photographs trace Siŋté Máza’s circulation in the non-Native world as an ambassador for Lakȟóta culture because they reveal him operating in spaces beyond Wild West performance. The album page—assembled by an unknown individual—offers in microcosm the array of identities through which Siŋté Máza transited: Lakȟóta performer on stage, offstage holding a rolled-up US flag, and Wyoming hunter posing in a commercial portrait studio.

Conclusion

In a 2018 talk at the Association of Historians of American Art Biennial Symposium, photo historian Monica Bravo interpreted photographs of human sitters as existing across a spectrum between portrait and type, framed by the contingencies of context.94 In myriad visual representations, Siŋté Máza enacts such a range, appearing as an archetype as well as an individual, sometimes simultaneously within the same image. These representations are not straightforward, nor are their meanings fixed. For instance, based on appearances, we might quickly assign Käsebier’s first photograph of Siŋté Máza as revealing the sitter’s greater presence and rejection of stereotype (fig. 2). Yet the artist claims a heavy-handed intervention in her sitter’s clothing and pose to render him vulnerable, and she featured the image that her sitter purportedly rejected as the frontispiece for Everybody’s Magazine. She also narrated that the sitter more greatly controlled and preferred the second photograph, which aligns more visibly with the stereotypes set forth in typical representations of him (fig. 3). Siŋté Máza in Rome, too, both informs stereotypes and surpasses them. A postcard version of one photograph tried to construe him as an Indian incongruous with his space, yet some of the details of the image work against that argument (fig. 9). By sitting next to plaster models of iconic Americans, he deflects archetyping and instead, challenges viewers to see the fictive possibilities of representation (fig. 11). Hiscock’s photographs (figs. 12, 14, 15) build a different layered image of Siŋté Máza’s many transits. They may have circulated beyond the sitter’s private commission, with resonances and meanings that shifted as they moved.

These three case studies suggest contingent vicissitudes of identity projection between self and performer. Representations of Siŋté Máza wearing regalia were not necessarily beyond his control and did not automatically fix him as a racialized type, nor were images of him outside of Lakȟóta regalia entirely liberated from projections of stereotype. Collectively, Siŋté Máza’s photographs show how he navigated relational movement to enact transit, to selectively upend expectations, and to deflect fixity. If the photographs in “The Indian and the Auto” suggest stasis while the illustrations render movement (fig. 1), the wider array of photographs for which the Lakȟóta performer posed between 1898 and 1908, read contextually, emphasize his dynamic and relational transit in the metaphorical sense established by Byrd, which frames disruptive spaces for American Indians to deflect stereotype by leveraging the loose metaphor of the Indian in US imperialist projections. Active circulation undergirded these photographic opportunities, from the movements of bodies, of Native-made regalia, and of the photographic image itself. Siŋté Máza selectively fashioned himself by turns both as the stereotypical Plains Indian he portrayed in wild west shows and as an individual, underscoring his fluidity and adaptability in the non-Native world.

Siŋté Máza reveals an interwoven and adaptable identity construction that embraces the photographic medium as an asset. The photographs underscore the complexities in interpreting interactions between a photographer who uses a medium inextricably tied with histories of racialization and settler colonial expansion, and a sitter from an American Indian nation that the United States was attempting to erase. As a collaborator in the production of images he treated as a medium of possibility rather than oppression, Siŋté Máza simultaneously performs the “raw Indian” and archetypal Indian chief that Käsebier helped to build, the cosmopolitan artist in a Roman café, the sporter of Lakȟóta and Cree regalia, and the western hunter integrated into settler society. For him, all these identities were modern. These layered identities represent ambivalent circulations in a complex world that interwove tradition and modernity and coexisting Native and non-Native communities. His photographs show that it is possible to read US photography both with and against the grain to find spaces of complicity and contestation, agency and voice in cultivating modern Lakȟóta identities.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Monica Bravo, Emily Voelker, John Bowles, and Alix Beeston for their feedback on this essay, Jessica Skwire Routhier for her copy edits, and to Tawa Ducheneaux at the Woksapi Tipi and Lakȟóta elders for assistance with Lakȟóta names. For their support of this research, my thanks to Dine Dellenback, Naoma Tate, Jeremy Johnston, Deb Adams, Sam Hanna, Mary Robinson, Karen Roles, Karen Preis, Hunter Old Elk, Rebecca West, Karen McWhorter, Nicole Harrison, Peter H. Hassrick, and Sylvia Hueber, with the Buffalo Bill Center of the West; the Buffalo Bill Museum & Grave; Brian Beauvais from the Park County Archives; Catherine Harvey from the Hastings Museum & Gallery; Jill Ahlberg Yohe from the Minneapolis Institute of Arts; Steve Friesen; and Richard Green. I also received productive feedback on this research at the College Art Association 2020 meeting at a panel “Emerging Subjects: Portrait and Type in the Nineteenth-Century Americas,” organized by Jill Vaum Rothschild and Phillip Troutman, from the chairs, fellow speakers Mey-Yen Moriuchi and Margarita Karasoulas, and from attendees Tanya Sheehan and Chloë Courtney.

November 30, 2020: An earlier version of this article gave the Lakȟóta name for Has No Horses as Tasunga Nice. The corrected name of Śuŋkaḱaŋ Nica has been confirmed with descendants of the family.

Author’s note, November 11, 2023: The original version of this article misidentified as dentalia what are hairpipe bone beads. My thanks to Arthur Amiotte for this correction, as well as for ongoing feedback on my scholarship on Lakȟóta art and culture.

Cite this article: Emily C. Burns, “Siŋté Máza (Iron Tail)’s Photographic Opportunities: The Transit of Lakȟóta Performance and Arts,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 6, no. 2 (Fall 2020), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.10913.

PDF: Burns, Siŋté Máza

Notes

- I use the term “Indian” purposefully to refer to non-Native constructions and stereotypes of Native American identity, and “American Indian,” “Native American,” or the name of respective Native nations to refer to individual communities and cultures. Emily C. Burns, Transnational Frontiers: the American West in France (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2018), 171n5. I refer to individuals by their Lakȟóta names, using orthography from Jan Ullrich, New Lakota Dictionary, 2nd ed. (Bloomington, IN: Lakota Language Consortium, 2008). ↵

- “The Indian and the Auto: A Meeting of Extremes,” San Francisco Call, September 1, 1907, 16. ↵

- Philip J. Deloria, Indians in Unexpected Places (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2004), 3–14. ↵

- On the scrapbook, see Ellen Gruber Garvey, Writing with Scissors: American Scrapbooks from the Civil War to the Harlem Renaissance (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012). ↵

- Gerald Vizenor, Manifest Manners: Postindian Warriors of Survivance (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1999). ↵

- I thank Deb Adams at the William F. Cody papers at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West for collating these census records from Indian Census Rolls, 1885–1940, Records of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, RG 75, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC (hereafter NARA). ↵

- Philip Iron Tail Information Card, Carlisle Indian Industrial school, RG 75, Series 1328, box 2, NARA; “Iron Tail,” Indian Helper 12, no. 44 (August 13, 1897): 1, 4; and Cindy Fent and Raymond Wilson, “Indians Off Track: Cody’s Wild West and the Train Wreck of 1904,” American Indian Culture and Research Journal 18, no. 3 (1994): 235–49. Some of the Census records list the name of Siŋté Máza’s second wife as “Red House” and as “Red Horn.” ↵

- “Iron Tail,” 1, 4. This album was acquired in 2019 by the McCracken Research Library at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West (hereafter McCracken). ↵

- See, for instance, Maurice Frink, “Iron Tail—he was a good Indian,” Empire Magazine, September 24, 1967, 16. ↵

- M. I. McCreight, The Wigwam: Puffs from the Peace Pipe (Sykesville, PA: Nupp Printing Co., 1943), 11. Frink likewise concludes, “Iron Tail was neither great nor a chief. He was just a good man” (Frink, “Iron Tail,” 17). ↵

- “WH-O-O-O-P! Iron Tail and His Braves Come: But They Travel on to the Rising Sun This Morning. Some 40 Going to France,” New York Times, February 8, 1905; “’Lamping’ Chief Iron Tail: For Five Cents You Can See His Image, But It Takes Cigarettes and Peach Pie to Meet the Original,” University Missourian, October 2, 1912; “Only One Chief Iron Tail,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, June 24, 1913, 11. For French references, see clippings in Gil Blas, April 10, 1905; Aurore, April 11, 1905; and “Les Vrais Peaux-Rouges,” Le Matin, April 22, 1905, France 1905-6 scrapbook, MS 6 William F. Cody Collection, 1840-2011, McCracken. ↵

- Dean Krakel, End of the Trail: The Odyssey of a Statue (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1973), 25–26; “What the Indian on the Nickel Thinks About Money,” Indianapolis Star, May 31, 1914, SM5; “Iron Tail Proud Because His Head is Upon Nickel,” Syracuse Herald, July 5, 1913, 12; and “Iron Tail’s Profile Adorns New Nickels,” Amsterdam Evening Recorder, July 18, 1914, 2. ↵

- Photographs of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West tour in France in 1905–6, for instance, depict the performers in parades in automobiles. See “En Automobile dans le ‘Far West,’” Les Sports, April 22, 1905, France 1905–6 scrapbook, McCracken. ↵

- On Lakȟóta performers in Buffalo Bill’s Wild West, see Joy S. Kasson, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West: Celebrity, Memory, and Popular History (New York: Hill and Wang, 2000); Linda Scarangella McNenly, Native Performers in Wild West Shows: From Buffalo Bill to Euro Disney (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2012); Steve Friesen, Lakota Performers in Europe: Their Culture and the Artifacts They Left Behind (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2017); and Burns, Transnational Frontiers. On Plains Indians as the archetypal Indian, see John C. Ewers, “The Emergence of the Plains Indian as the Symbol of the North American Indian,” in Smithsonian Institution, Annual Report, 1964 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1965), 531–44; and Phyllis Rogers, “‘Buffalo Bill’ and the Siouan Image,” American Indian Culture and Research Journal 7, no. 3 (1983): 43–53. ↵

- On the links between photography and US colonialism, see Jolene Rickard, “The Occupation of Indigenous Space as ‘Photograph,’” in Native Nations: Journeys in American Photography, ed. Jane Alison (London: Barbican Art Gallery, 1991), 57–71. ↵

- Kasson, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West, 198. On postcards and possession, see Susan Stewart, On Longing: Narratives of the Miniature, the Gigantic, the Souvenir, the Collection (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1984), 137. On vanishing race discourse, see Brian W. Dippie, The Vanishing American: White Attitudes and U.S. Indian Policy (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 1982). ↵

- Christopher Pinney, “Notes from the Surface of the Image: Photography, Postcolonialism, and Vernacular Modernism,” in Photography’s Other Histories, ed. Christopher Pinney and Nicolas Peterson (Durham: Duke University Press, 2003), 211. ↵

- McNenly, Native Performers, 12. ↵

- McNenly, Native Performers, 12–13, 14. ↵

- McNenly, Native Performers, 15. ↵

- Kate Flint, The Transatlantic Indian, 1776–1930 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2009), 246. ↵

- Kasson, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West, 85. ↵

- “Indians in the Wild West Show: Even When Not Performing They Wear Native Dress,” New York Times, April 21, 1901, 20. See also Laura Peers, Playing Ourselves: Interpreting Native Histories at Historic Reconstructions (Lanham, MD: AltaMira Press, 2007), 44–45, 60. ↵

- Other arguments of aesthetic collaboration between photographer and sitter have been made in Shamoon Zamir, The Gift of the Face: Portraiture and Time in Edward S. Curtis’s the North American Indian (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2014), 3; Shamoon Zamir, “Native Agency and the Making of the North American Indian: Alexander B. Upshaw and Edward S. Curtis,” American Indian Quarterly 31, no. 4 (Fall 2007): 613–53; and Wanda Corn, Georgia O’Keeffe: Living Modern (Brooklyn: Brooklyn Museum, 2017). ↵

- See Photograph Collection, Buffalo Bill Museum and Grave, Golden, CO: Buffalo Bill’s Wild West performers swimming (71.0106; 71.0142, Unit 2, Section 1, Shelf 1, Box 1A); Johnny Baker with wife and child, Iron Tail, and Sam Lone Bear (71.0149; Unit 2, Section 1, Shelf 1, Box 1B); Johnny Baker and family with Iron Tail (71.01.0142; Unit 2, Section 1, Shelf 1, Box 1B); and Johnny Baker, Nate Salsbury, Iron Tail, and others at dining room table (72.0198; Unit 2, Section 2, Shelf 1, Box 2B). ↵

- This revision is framed by calls to attend to “coproductions of modernity in all their varieties.” See Elizabeth Harney and Ruth B. Phillips, “Introduction: Inside Modernity, Indigeneity, Coloniality, Modernisms,” in Mapping Modernisms: Art, Indigeneity, Colonialism, ed. Elizabeth Harney and Ruth B. Phillips (Durham: Duke University Press, 2018), 23. ↵

- Jodi A. Byrd, The Transit of Empire: Indigenous Critiques of Colonialism (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2011), xxi. ↵

- Byrd, The Transit of Empire, 73. ↵

- Byrd, The Transit of Empire, xvi–xvii. On mobility and movement as key to Indigenous modernisms, see also Harney and Phillips, “Introduction,” 19–21. ↵

- See Catherine Price, The Oglala People, 1841–1879: A Political History (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1996); Jeffrey Ostler, The Plains Sioux and U.S. Colonialism from Lewis and Clark to Wounded Knee (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004); and Robert M. Utley, The Last Days of the Sioux Nation, 2nd ed. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004). ↵

- Rickard, “Occupation of Space,” 71. ↵

- Jolene Rickard, “Visualizing Sovereignty in the Time of Biometric Sensors,” South Atlantic Quarterly 110 (2011): 471. ↵

- “Indians at a Studio Tea,” New York Times, April 10, 1898, 14; “Sioux Chiefs’ Party Calls,” New York Times, April 24, 1898, 14. Later commentary about those visits is found in “The Indian as a Gentleman,” New York Times, April 23, 1899, 20; and “Wild West Show Enters Newport,” The World (New York), June 25, 1899, 2. See also Michelle Delaney, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Warriors: A Photographic History of Native American Performers by Gertrude Käsebier (Washington, DC: Smithsonian National Museum of American History, 2007), 79; Deborah Jane Marshall, “The Indian Portraits,” in A Pictorial Heritage: The Photography of Gertrude Käsebier, ed. William Innes Homer (Newark: University of Delaware, 1979), 31–32; and Barbara L. Michaels, Gertrude Käsebier: The Photographer and Her Photographs (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1992), 34. ↵

- “Some Indian Portraits,” Everybody’s Magazine 4 (January 1901): 2. On Käsebier’s images of Zitkála-Šá, see Elizabeth Hutchinson, “Native American Identity in the Making: Gertrude Käsebier’s ‘Girl with the Violin,’” Exposure 33, no. 1/2 (2000): 21–32. ↵

- “Some Indian Portraits,” 7. For other reproductions from this series, see Elizabeth Hutchinson, “When the ‘Sioux Chief’s Party Calls’: Käsebier’s Indian Portraits and the Gendering of the Artist’s Studio,” American Art 16, no. 2 (Summer 2002): 64n2. ↵

- “Some Indian Portraits,” 9. ↵

- Rayna Green, “Gertrude Käsebier’s ‘Indian’ Photographs: More than Meets the Eye,” History of Photography 24 (2000): 58–60; and Jennifer Sheffield Currie, “Gertrude Käsebier’s Native American Portraits,” in Dimensions of Native America: The Contact Zone, by Jehanne Teilhet-Fisk and Robin Franklin Nigh (Tallahassee, FL: Museum of Fine Arts, School of Visual Arts and Dance, Florida State University, 1998), 114–19. A handful of photographs suggest that Käsebier also visited South Dakota, but the date and details of this trip are yet undocumented. See Sioux Indians on the Plains (PG.69.236.001) and three photographs titled Sioux Indians on the Dakota Plains (PG.69.236.002; PG.69.236.003; PG.69.236.004), National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution. ↵

- Lauren Kroiz, Creative Composites: Modernism, Race and the Stieglitz Circle (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012), 36. ↵

- Judith Fryer Davidov, Women’s Camera Work: Self/Body/Other in American Visual Culture (Durham: Duke University Press, 1998), 97. ↵

- Laura Wexler, Tender Violence: Domestic Visions in an Age of U.S. Imperialism (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2000), 178–81. ↵

- Hutchinson, “When the ‘Sioux Chief’s Party Calls,’” 51–65; and Elizabeth Hutchinson, The Indian Craze: Primitivism, Modernism, and Transculturation in American Art, 1890–1915 (Durham: Duke University Press, 2009), 142. ↵

- Currie, “Gertrude Käsebier’s Native American Portraits,” 117. ↵

- Davidov, Women’s Camera Work, 97. ↵

- Wexler, Tender Violence, 202. ↵

- “Photographing a Real Indian,” New York Times, December 30, 1900, 17. This language is repeated verbatim in “Some Indian Portraits,” 7. ↵

- A collection of platinum prints from this series is in the National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC. Käsebier’s glass plate negatives are held by the Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress, Washington, DC (Series LC-K2, numbers 53-104). The library made prints from these negatives in 1964, catalogued as Lot 10136. For more on the use of profile and full-face views in anthropological photography, see Michelle Smiley, “Daguerreotypes and Humbugs: Pwan-Ye-Koo, Racial Science, and the Circulation of Ethnographic Images around 1850,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 6, no. 2 (Fall 2020), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.10895. ↵

- “Some Indian Portraits,” 7, 12. ↵

- “Sioux Chiefs’ Party Calls,” 14. ↵

- Tanya Sheehan, Study in Black and White: Photography, Race, Humor (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2018), 2, 12. See also Darcy Grimaldo Grigsby, “Negative-Positive Truths,” Representations 113 (Winter 2011): 22–23, 31. ↵

- H. J. Rodgers, Twenty-Three Years Under a Sky-Light, or Life and Experiences of a Photographer (Hartford: H. J. Rodgers, 1872), 175–76, cited in Sheehan, Study in Black and White, 29–30. ↵

- “Sioux Chiefs’ Party Calls,” 14. ↵

- On Käsebier lightening the faces of other American Indian sitters, see Kathleen Pyne, Modernism and the Feminine Voice: O’Keeffe and the Women of the Stieglitz Circle (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007), 38. ↵

- “Some Indian Portraits,” 7. ↵

- Kroiz, Creative Composites, 36. ↵

- Friesen, Lakota Performers, 15–20; Burns, Transnational Frontiers, 48; and Colin Taylor, “Wo’wapi Waśte: Acting the Part: Image Makers of the North American Indian,” in Alison, Native Nations, 205–22. ↵

- On the emphasis on the studio space within the photographs, see Hutchinson, “When the ‘Sioux Chief’s Party Calls,’” 46–47. ↵

- The caption in “Some Indian Portraits” mislabels the figure closest to the viewer as Iron Tail. ↵

- The inscription is occluded by the pasted print. ↵

- Janet Berlo, ed., Plains Indian Drawings 1865–1935: Pages from A Visual History (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1996). ↵

- Kristine K. Ronan, with Allan McLeod, “Káma-Kapúska! Making Marks in Indian Country, 1833–34,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 18, no. 2 (Autumn 2019): 8–11, https://doi.org/10.29411/ncaw.2019.18.2.23. ↵

- “Gems of Native Art from the Wild West Indian: The White Man and His Squaw and their Doings, as Portrayed by the Red Man’s Pencil,” New York Recorder, July 22, 1890; and “A Few Life Sketches By One Star Bear, the Great Sioux Artist,” New York World, September 9, 1894, both in Buffalo Bill’s Wild West scrapbooks, MS6, McCracken. See also “The Artist of the Sioux,” New York World, September 8, 1894, 2. ↵

- Sioux and Wigwam, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Camp (69.236.065); High Heron, Sioux Indian in Camp, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West (69.236.066); Portrait of Little Finger, Sioux Indian (69.236.008); Black Horse, Sioux Indian (69.236.010); Spotted-Tail, Sioux Indian (69.236.013), National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution. ↵

- Wexler, Tender Violence, 201. ↵

- Wexler, Tender Violence, 202. ↵

- Carrie A. Lynford, Quill and Beadwork of the Western Sioux (Boulder: Johnson Books, 1979), 74. ↵

- Marsha Clift Bol, “Defining Lakota Tourist Art, 1880–1915,” in Unpacking Culture: Art and Commodity in Colonial and Postcolonial Worlds, ed. Ruth B. Phillips and Christopher Steiner (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999), 223. See also Friesen, Lakota Performers; and Emily C. Burns, “Circulating Regalia and Lakȟóta Survivance, c. 1900.” Arts Magazine 8, no. 146 (2019): https://www.mdpi.com/2076-0752/8/4/146. After World War I, increasing numbers of beaded objects could be acquired through trade catalogues. ↵

- Burns, “Circulating Regalia”; McNenly, Native Performers, 90–99; Marsha Clift Bol, “Lakota Women’s Artistic Strategies in Support of the Social System,” American Indian Culture and Research Journal 9 (1985): 33–51; Marsha Clift Bol, “Lakota Beaded Costumes of the Early Reservation Era,” in Arts of Africa, Oceania and the Americas: Selected Readings, ed. Janet Catherine Berlo and Lee Ann Wilson (Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall, 1993), 363–70; and Marsha C. Bol, The Art and Tradition of Beadwork (Layton: Gibbon Smith, 2018), 220. ↵

- L. G. Moses, Wild West Shows and the Images of American Indians, 1883–1933 (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1996), 7–8; Sam A. Maddra, Hostiles? The Lakota Ghost Dance and Buffalo Bill’s Wild West (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2006); McNenly, Native Performers; and Burns, Transnational Frontiers, 16, 58–64. ↵

- Luther Standing Bear, My People, the Sioux (1928; repr., Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1975), 259, 261. ↵

- Burns, Transnational Frontiers, 119–41. ↵

- On the Wild West in Italy, see Rita G. Napier, “Across the Big Water: American Indians’ Perceptions of Europe and Europeans, 1887–1906,” in Indians and Europe, An Interdisciplinary Collection of Essays, ed. by Christian F. Feest (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1999), 383–401; and Daniele Fiorentino, “‘Those Red-Brick Faces’: European Press Reactions to the Indians of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show,” in Feest, Indians and Europe, 403–13. ↵

- Angela Giuffrida, “‘The most important people have been here’: Rome’s oldest cafe fears closure,” Guardian, October 18, 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/oct/18/caffe-greco-rome-oldest-cafe-fears-closure. ↵

- The show performed in Rome March 22–28, 1906, so dating can be closely approximated. ↵

- On this photograph, see also Gloria Bell, “The Eloquence of Things: Indigeneity and the 1925 Pontifical Missionary Exhibition” (PhD diss., University of British Columbia, 2018), 91–93. ↵

- Pinney, “Notes from the Surface,” 204. ↵

- On Burke and his role in building Wild West celebrity, see Joe Dobrow, Pioneers of Promotion: How Press Agents for Buffalo Bill, P. T. Barnum, and the World’s Columbian Exposition Created Modern Marketing (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2018). ↵

- Arjun Appadurai, “The Colonial Backdrop,” Afterimage 24 (March/April 1997): 4, 6. ↵

- Deborah Poole, “An Excess of Description: Ethnography, Race, and Visual Technologies,” Annual Review of Anthropology 34 (2005): 159–79, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.anthro.33.070203.144034. ↵

- Pinney, “Notes from the Surface,” 202. ↵

- Pinney, “Notes from the Surface,” 211. ↵

- “Col. Cody and Party Start Out on a Hunt: A Jolly Crowd Bent Upon Having a Good Time,” Cody Enterprise, November 14, 1901, and “A Great Hunt! Colonel Coy and Party Get all Kings of Game: One of the Happiest Crowds of the Season,” Cody Enterprise, December 5, 1901, clippings in the Park County Archives, Cody, Wyoming (hereafter Park County Archives), 06-01; and Helen Gray, “On a Hunt for Elk with ‘Buffalo Bill’,” Los Angeles Times, December 2, 1906, IL7. See also McCreight, The Wigwam, 11; Don Russell, The Lives and Legends of Buffalo Bill (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1960), 431; and W. Hudson Kensel, Pahaska Tepee: Buffalo Bill’s Old Hunting Lodge and Hotel, a History, 1901-1946 (Cody: Buffalo Bill Center of the West, 1987). ↵

- Hiscock’s first advertisement in the Cody Enterprise appeared on December 1, 1904, Park County Archives. On Hiscock, see Amber Peabody, “The Picture Man: F. J. Hiscock, Sharing Wonders of Cody through Photographs,” Legends (Summer 2013): 53–55; and “F. J. Hiscock—the picture man,” Cody Country Yesterday 2 (June 2004): 9–10; and “Hiscock sells his photos over the U.S.,” 13–14. ↵

- W. F. Cody to F. J. Hiscock, September 12, 1910, copy in the Park County Archives. ↵

- Native commissions for studio portraits were not uncommon. See, for instance, Tom Jones, Michael Schmudlach, and Matthew Daniel Mason, People of the Big Voice: Photographs of Ho-Chunk Families by Charles Van Schaick (Madison: Wisconsin Historical Society Press, 2014). ↵

- Similarly performative is Hiscock’s photograph of cowboy Chalsey Spangler posing with pistol, rifle, and rope, c. 1905, P02-73-062, Park County Archives. ↵

- This painted backdrop appears in other Hiscock portraits in the Park County Archives: Studio Portrait of Dallas A. Tinkcom, Benjamin F. Martin, & Mahlon Frost (P89-40-045) and Unknown Man with Child (P17-17-209). ↵

- On Cree beadwork, see Lois S. Dubin, Floral Journey: Native North American Beadwork (Los Angeles: Autry National Center of the American West, 2014), 107–8, 116. ↵

- “Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show Center of Local Interest Today: Two Unique Figures in Show,” Constitution (Atlanta), October 7, 1907, 4. ↵

- My thanks to Hunter Old Elk for looking at and discussing this garment with me. This pictorial beadwork may be Lakȟóta or Dakȟóta-made, with its production probably tied to the Standing Rock Sioux nation, which comprises bands from both communities. See Dennis Lessard, “Pictographic Sioux Beadwork: a Re-examination,” American Indian Art Magazine 16, no. 4 (Autumn 1991): 70–74; Susan Power, “Nellie Two Bears Gates: Chronicling History through Beadwork,” in Hearts of our People: Native Women Artists, ed. by Jill Ahlberg Yohe and Teri Greeves (Minneapolis: Minneapolis Institute of Art, 2019), 193; and Burns, “Circulating Regalia,” 10–12. ↵

- Janet Catherine Berlo and Arthur Amiotte, “Generosity, Trade and Reciprocity among the Lakota: Three Moments in Time,” in Plains Indian Art of the Early Reservation Era: the Donald Danforth Jr. collection at the Saint Louis Art Museum, ed. Jill Ahlberg Yohe (Saint Louis: Saint Louis Art Museum, 2016), 31–72; and Adriana Greci Green, “Performances and celebrations: Displaying Lakota Identity, 1880–1915” (PhD diss., Rutgers University, 2001), 64–69. ↵

- Carmen Robertson, “Land and Beaded Identity: Shaping Art Histories of Indigenous Women of the Flatland,” RACAR 42, no. 2 (2017): 20, https://doi.org/10.7202/1042943ar. See also Burns, “Circulating Regalia,” 12–13. ↵

- War bonnets tentatively linked with Siŋté Máza’s travels are in the collections of the Hastings Museum, UK, and the Buffalo Bill Museum and Grave, Golden, Colorado. See Colin Taylor, “Iron Tail’s War Bonnet,” American Indian Crafts and Culture 5, no. 5 (1971): 6–7, 12; and Richard Green, “Iron Tail’s Warbonnet: in the Buffalo Bill Museum, Lookout Mountain,” Whispering Wind 38, no. 5 (May–June 2009): 20–23. ↵

- Park County Archives. ↵

- Monica Bravo, “The Portrait and the Type: Tony Luhan Through the Lenses of Ansel Adams and Edward S. Curtis” (paper presented at the Association of Historians of American Art Biennial Symposium, Minneapolis, October 6, 2018). ↵

About the Author(s): Emily C. Burns is Associate Professor in the Department of Art and Art History at Auburn University